I was not present for the opening of Philharmonic Hall in 1962--I was seventeen--but I did attend performances during its first season. (The Met performed there, it should be said, with the American premiere of Manuel De Falla's Atlàntida, and even more significantly, on the second night of concerts in the hall, Erich Leinsdorf, the Boston Symphony, and pianist John Browning performed the world premiere of a new piano concerto by none other than Samuel Barber.)

There was a Bach B-minor Mass and a concert of John Cage's music in which I remember seeing Merce Cunningham, shoeless and in tights, riding a bicycle onstage. I also remember how much I loved Philharmonic Hall. The walls and ceiling were a deep midnight blue, and the seats and the acoustical "clouds" were various shades of gold. Yes, perhaps it sounded like a really good car radio, but rarely have I felt so comfortable and uplifted in an architectural-musical space as I did in its earliest iteration. And although the acoustics took a hit from some of the critics, within a day or so they had been altered (by adjusting the "clouds") and John Chapman of The Daily News pointed out how "there is no doubt in my mind that the hall itself will be a great musical instrument." The negative assessment, however, has stuck, and, as of this writing, the Philharmonic is hoping to raise a half a billion dollars to fix the hall.

After all the excitement of the opening of Philharmonic Hall, all of us in 1966 wondered what the new Met experience would be--both musically and aesthetically. Every ticket holder had already received an elegant program page designed by Julian Tomchin, extravagantly printed in Japan on pure silk bridal satin, and backed with Sea Island cotton. Entering the building was unquestionably thrilling. The old house had no plaza in front of it. It had no lobby per se. What it had was a sense of history--Mahler, Puccini, Caruso, Toscanini. When you entered the old building, all you had were the ticket booths on the right and a wall of "8 by 10 glossies"--the phrase every artist knew: the official head shots in black and white. The Met would display these photos, one next to the other, in alphabetical order on that wall. If you were in the family circle you did not enter here, but had a separate entrance with an elevator to the top. The class distinction was ingrained in the old house, but wherever you sat, it was classy inside. Up top, you had a magnificent view of that chandelier and down below there was Sherry's restaurant and crush bar with its bright red cut-velvet wallpaper.

With the new opera house, however, there was grandeur from the moment you approached the house and entered the lobby. As a sometime-college-architecture student, I had heard that the lobby had been compromised and was meant to be a lot larger. Nevertheless, its curves and the red carpet gave the Met something it never had before--uplift. The two murals by Marc Chagall, each measuring 30 x 35 feet, brought accessible contemporary art into the foyer, with the tree of life floating--surprisingly--above the Hudson River. The plaza was buzzing that night with famous people dressed magnificently and mingling with those of us who managed to get in--and those outside staring at all of us. America's First Lady, Lady Bird Johnson, purred to the press in her broad Texas accent that grated on New York's ears when she spoke of "all the gold and glittuh." The English actress Hermione Gingold, who was as famous for her baritone voice with its lisping consonants as she was for pithy remarks, said of the auditorium, "It looks like it was decorated by a madam."

Indeed, the auditorium itself was another matter. The walls were highly polished rosewood. The proscenium was painted in pure and dazzling gold. Above it was a sculpture by Mary Callery that reminded many of a deconstructed garbage can. I read about it in the program and said to Aunt Rose, "It was designed by a woman," to which Rose said, "That's no surprise." I was 21, after all, and understood that Rose thought all those pipes were phallic. Ornamentation was a serious challenge for architects in that era and I was interested in this solution, a sculpture that replaced those composers' name that had announced themselves from the equivalent perch in the old house. However, as I stared at the texture that had been applied to the area around the proscenium, I knew it looked somehow familiar but could not place it. After about an hour of thought I realized it was the pattern on Marcal paper dinner napkins.

The ceiling was a cream color and the lighting on the boxes looked like Cheshire cat smiles. The Swarovski crystal satellite chandeliers--a gift from the Vienna State Opera in thanks for the United States' assistance in rebuilding their opera house after we had bombed it in March of 1945--seemed too small, or perhaps there weren't enough of them for the space they were meant to inhabit. Sitting in the dress circle, I could view the performance either by looking at the stage or by watching its reflection in the walls--the proscenium was brighter than anything onstage. A blank cream ceiling ellipse surrounded by dazzling gold that continued down and around the proscenium, bright red carpets and seats, polished brownish-red wood walls, and little sparkling crystal chandeliers that went up and down seemed to compete with each other disproportionately.

Of course, knowing everything can be a burden--especially for a 21-year-old. Over the years, the Met has muted all its colors and cut off the "smiles" so that the crystal lights on the boxes are rectangles now. The proscenium's paint job is now a matte and darkened golden color. The walls do not reflect. The saloon red is now more of an understated burgundy. All of it has been made to look old, even as it has actually aged--and as it has become an iconic midcentury hall, its design floating somewhere between the 19th century excesses of the Paris Opéra's Salle Garnier, Covent Garden's glorious royal living room of an auditorium, Milan's Teatro alla Scala, and their architectural opposite: the 1967 brutalist Teatro Regio in Turin, which looks like the set for Star Trek. Wallace Harrison and his team found a middle road, one that sings of Camelot--both the Broadway show that was designed by Oliver Smith and the Kennedy Era.

Sensory overload had a new meaning for me that night in 1966, even before I heard a note of the new opera. Just the sounds of the orchestra--beginning as it always had with lone harpist tuning before the racket of her colleagues obliterated her ability to hear--entering and playing their scales and excerpts of what was to come--were overwhelming. One could not escape the fact that the auditorium was a great space: huge, in comparison to the old house, and with vastly improved sightlines (no weight-bearing pillars!). The relationship between the stage and us in the audience was both inviting and epic.

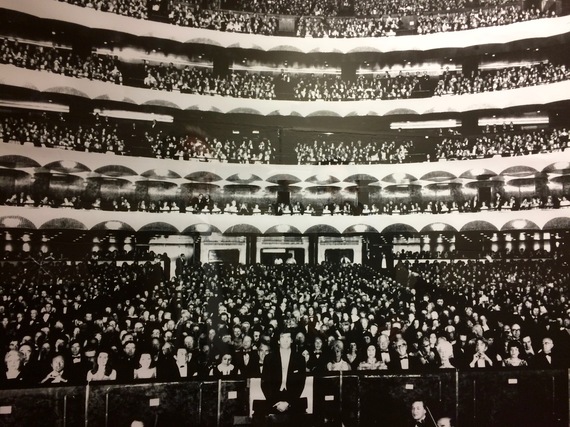

When maestro Thomas Schippers entered the pit, there was an enormous ovation. A photo of all of us was taken from the stage. The first piece we heard was the "Star Spangled Banner." It was hard to know what the acoustics were like because we were all standing and singing. Once we settled back down and the lights in the auditorium went to black, there were speeches, and finally, it was time for an opera: new music played in a new hall and we--the lucky 4,000--were there. How would it sound?

Many of us knew that the Met was taking no chances and had diverted a student matinee on April 16, 1966 to the new house to try it out five months before its official opening. That performance did begin with a bang: cannon shots were fired from the stage to test acoustical reverberation and decay rates. What followed was an opera the Met had commissioned in 1910, Puccini's La Fanciulla del West. Those kids and their teachers were the first ones, but, on September 16, at about 8:15 pm, we all got very quiet indeed, to hear. Yes, finally, to hear.

And BANG! a glorious fanfare for the brass. Tah-tah-tah-TAH-duh. Tah-tah-tah-TAH-duh. Tah-tah-tah-TAH-DAH! An amazingly fast curtain parted to reveal a first image--nothing less than what Zeffirelli called "The Empire"--with the Met chorus singing "From Alexandria this is the news." The libretto indicates that this enormous double chorus represents "Romans, Greeks, Jews, Persian, Africans, [and] Soldiers" and that is what was on that stage.

Few words were comprehensible, with the exception of "Antony fishes," or was it "Antony wishes?" Counterpoint is the enemy of textural comprehensibility, and even if Barber had determined the audience needed to understand the libretto, Shakespeare would have tripped him up with, "Leave thy lascivious wassails!"

Barber had broken a century of convention by making the hero, Antony, a baritone. Ever since Mozart told us the truth about the two sets of lovers in Così fan tutte--a soprano with a tenor, and a mezzo-soprano with a baritone (even as they swap around for two acts)--opera has been about sopranos and tenors as lovers. The baritone is inevitably the villain or the sadly unrequited. The mezzo usually gets an aria, but doesn't get the man. Mess with that and you are messing with your audience. But Barber had something else in mind: the warm colors of Leontyne Price's voice and the way it would blend with a glorious and youthful baritone of Justino Diaz.

A short second scene in Cleopatra's palace in Alexandria gave us the first solo sounds to bounce off the new stage. Antony sang, "These strong Egyptian fetters I must break or lose myself in dotage" and we understood the opera was actually in English--difficult English, but English nonetheless. An offstage chorus sang, "Cleopatra!" four times and Miss Price was brought on inside a moving pyramid that opened up to reveal her. (The pyramid had famously broken down at the dress rehearsal and stage hands had to rescue her by making an unexpected entrance in contemporary dress.)

Price was trapped in another way: a costume that made it all but impossible for her to move. Never a great actor, she could not even make use of her arms without bumping into her exploding quasi-Elizabethan dresses, or knocking off the exaggerated Egyptian wig that was more than twice the size of her head. At this point, we all began to have that creepy feeling one gets that things would not get better. We remained cautiously hopeful.

Indeed, there were still wonders to be heard and visions to be seen. (The intermissions were the other opera that was going on that night. And just before Act Three, general manager Rudolph Bing came to the stage to inform us that the orchestra had agreed to a new contract and that the season would continue. In a way, that news added a jolt of optimism to the proceedings that affixed itself to the opera.)

Barber had surprised us with unusual music--an entire scene accompanied by timpani to end Act Two; a scene in which five characters "improvise their own recitatives, without conductor or orchestra," while a "stick dance" takes place behind them that had been choreographed by Ailey--and Barber gave Miss Price an unforgettable aria before her suicide, "Give me my robe, put on my crown, I have Immortal longings in me," which began with a leitmotif that had been introduced earlier, making it feel like an old friend and yet completely new.

A rousing final chorus, with trumpets onstage, ended the evening with the word, "Rome." And when it was all over, we all had ... opinions! I rushed off to get the train back to New Haven and the next morning I ran into the avuncular master of Jonathan Edwards College, Beekman Cox Cannon, who had been my 20th century music history teacher and was a very grand seigneur. "Well, what did you think," he said gleefully, having listened to the radio broadcast. I said that I thought the music was awful and then I used an image of an overripe peach that had fallen from a tree and had begun to rot. "And the costumes," I said, knowing this would really get his goat. "You mean you were there? Why you son-of-a-bitch, tell me all about it!"

PART THREE concludes this memoire, in which we journey to the Met on the anniversary day, and the writer reassesses the opinions of a 21-year-old ...