Michael Henry Adams is a singular force in the New York historic preservation community. A Columbia-trained preservationist and local historian with encyclopedic knowledge of architecture and black history, he brings a passion and urgency to work in Harlem, driving far beyond simply writing letters and reports for the Landmarks Preservation Commission. He has advocated preservation for decades, but, with accelerating gentrification and repeated demolitions of historic structures, he has been forced into a more public and aggressive activism traditionally associated with other social movements. Adams makes connections between the neglect of historic preservation in Harlem and the structural racism behind gentrification and mass imprisonment. He firmly advances an argument that historical understanding is necessary to build a strong black identity, anchored in a collective past, that can defend against processes that may turn Harlem and other black neighborhoods "white."

In November of last year, Adams was arrested for chanting "Save Harlem Now" at the site of the Renaissance Ballroom and Casino, an iconic community location subject to imminent demolition. He is now suing the NYPD for violating his right to free speech. Incredibly and outrageously, the "Renny" was demolished last March, yet Adams continues to fight for other historic structures that he tracks and has cataloged. Because of connections I see between the struggle to protect "Little Syria" in Downtown Manhattan and Adams' courageous efforts for preservation in Harlem, I have long wanted to interview him.

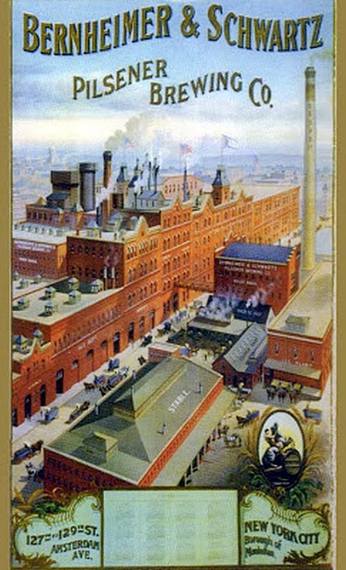

On Thursday, November 12, you and others are testifying at the Landmarks Preservation Commission to protect the Bernheimer & Schwartz Brewery Complex at 1361 Amsterdam Avenue in Manhattanville (also known as West Harlem). Why is this structure, that developers are now calling the "Mink Building," historically and architecturally important?

This landmark case is important not only for the merits of the structure, but for how the case will challenge and subvert the growing distortion of the landmarks law. Under New York's charter, a "landmark" is defined as "Any improvement, any part of which is thirty years old or older, which has a special character or special historical or aesthetic interest or value as part of the development, heritage or cultural characteristics of the city, state or nation."

The brewery complex has clear historical and aesthetic interest and value. When the complex was built, New York was the nation's leading beer producer: we brewed more beer than Milwaukee. And Manhattan had the most breweries. Of the two left on the island, this is the finest -- with ethnic German architectural motifs -- and the most complete. To visit this structure then is to experience Manhattanville's otherwise vanished, definitive industrial past. This property was calendared for consideration as a landmark decades ago. If a developer can thwart a twenty-five year effort to protect a structure so special and historic, through their power and by spreading around cash, then all of the surrounding Harlem is clearly doomed. Every reminder of the past will eventually vanish or become unrecognizable. That's what's at stake, that's why we have a landmarks law and federal tax incentives for preservation: to protect the irreplaceable heritage of the United States and of New York City from capricious destruction.

You have argued quite strongly that the government-facilitated destruction of Harlem's physical heritage aligns with attacks on the black population by mass imprisonment and economic exclusion. In what ways does the erasure of a community's identity, through gentrification and cavalier attitudes toward historic preservation, accelerate the destruction of a community itself?

The greatest reserve of affordable, rent-regulated housing in Manhattan is in the six-to-ten storey, early 20th-century apartment houses along the avenues. The number of units this stock entails by far exceeds Mayor Bill de Blasio's woefully inadequate and cynical mantra for "200,000 new and preserved" "affordable apartments." All over the city there is a case to be made for protecting these buildings. But apartments in Upper Manhattan -- in Harlem and elsewhere -- are not landmarked nearly to the degree they are Downtown. Statistically, in comparison, they are negligibly protected here at all. The same disparity holds true in the "outer boroughs." Failing to value and protect the architectural heritage of communities of color, and discounting and dismissing their culture, leads shortly to devaluation as a people. A tragic consequence is a loss of identity. And though it might not seem so, that's as destructive, in the end, as losing the local affordable housing stock.

You have been arrested several times in protests at sites where the demolition of a historic structure appears imminent. Sometimes these have been "solo [or] nearly solo demonstrations." What does it mean for you to put your body at risk at the site of a crime against historical memory and to take a stand, even if alone?

For decades, the old folks in our community warned that the "white man wants to take Harlem back." But for so long, since Harlem was such a troubled, broken-down and neglected place, we wouldn't believe them. Why have I risked harm for Harlem's old buildings? Beginning in the fall of last year, expecting the imminent destruction of the venerable Renaissance Ballroom and Casino, I started to process some intense emotions that I expressed in protest. Now that it's gone, I've been surprised: why do I still feel so angry and hurt? It is because this abandoned building and the rest of historic Harlem is a part of me. It represents who I am, in common and in community with other ignored and dismissed blacks, pushed aside to make way for whites, and to make profits.

Wanting to be fair, boasting a rainbow-like array of friends, for a long time I used to think that hoping for Harlem to remain a black Zion made me racist. No longer. For when no one else would live in this area, blacks gave Harlem purpose and value. We established its fame. Without Harlem, there would be no jazz, no black dance, and no contemporary urban fashion. Without the concentrated political power of Harlems across the country, there would be no black representation in American political life. Without Adam Powell, there is no President Obama. Somewhere, I believe there's got to be a place for me, for my people. And I refuse to apologize any longer for claiming Harlem as mine...