This month I am going to write about the painting that means the most to me, Giovanni Bellini's Ecstasy of St. Francis in the Frick Collection in Manhattan. By a stroke of luck it is included in the Google Art Project, so I can reproduce it in detail.

When I was young--maybe from the age of ten or twelve--I was entranced by this painting. I used to love it (I was sort of obsessed by it), but now it is largely ruined for me, and the reason is that I have read too much about it. My own profession of art history has poisoned the painting for me, and there is no way to get back to it.

This month I am going to introduce the painting, and see if I can convince you how absolutely astonishing it is, and next month I will explain how too much reading can undermine your experience of the visual world.

The painting shows Saint Francis, dressed in his monk's robes, looking up into the sky. He is barefoot (his sandals and walking stick are back at his little desk), and he is surrounded by a swirling sea of bluish rocks.

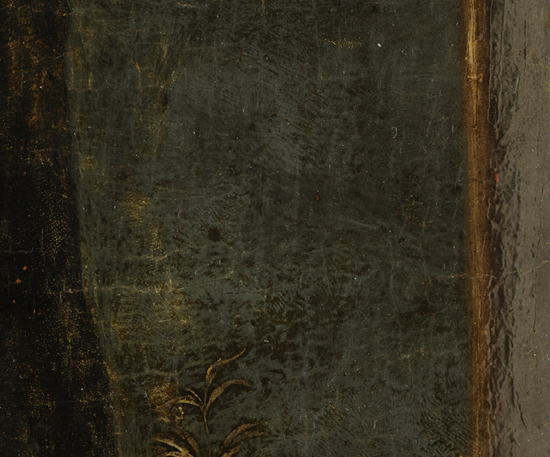

They're hypnotic, those rocks. Some look chalky and dry; others ooze like melting Jell-O.

Immediately above the saint's head, the cliff face divides and flows around him, as if he were a boulder in a stream. (Bellini may have been thinking of an early legend in which St. Francis escapes the devil by melting into the cliff. According to the story, the rocks parted like wax--a perfect match for the liquescent stones in the painting.)

Toward the top of the painting, an arc of yellowish rocks mimics the saint's pose.

Even the gatherings of fabric at his waistband are echoed in the tendrils of ivy spreading from a fissure in the rock.

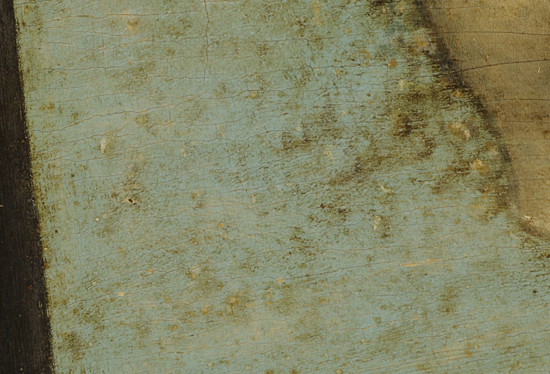

The color is a mystery. Some rocks are safety-glass blue. Others are bottle blue, or the blue of cold wet grass. The blue deepens downward, toward St. Francis's feet.

Above his head the cliffs are creamy; perhaps they are reflecting yellowish light from the afternoon sun.

As you look down, the cream dims to a fluorescent beige, and then darkens into a deep glowing turquoise. It looks as if St. Francis were wading in a chlorinated pool, moving slowly down toward the deep end.

Strangely, there is no green between the yellow and the blue. As any painter knows, that's a trick, since even a dab of blue paint will turn yellow into a bright leafy green. Somehow Bellini avoids that trap, and his yellows settle into somnolent blues, without even a hint of green.

Some of the blues are stained by browns--there are scatters of fine dirt, and a fuzz of blighted grass--but nothing around the saint is normal, healthy plant green.

Just under his right hand is the torn stump of a fig tree. Normally the inner wood and sap would be a tender sap green, but here the ripped surface reflects a wan yellowish light.

Even the juniper and orris root in the saint's garden have an odd blackish color.

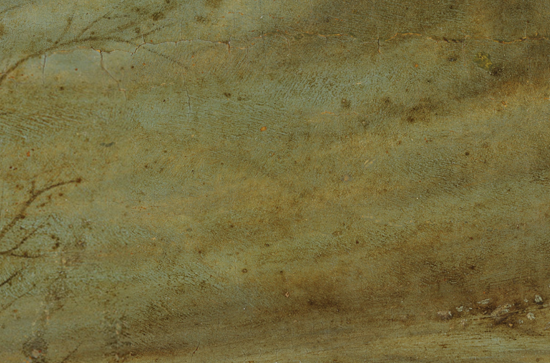

In the distance things have more ordinary hues. A pale brownish-gray donkey stands in a close-cropped field. The grass under its feet is parched and marred by thistles, but overall the field has the common color of grass.

Farther off, a shepherd herds a dozen sheep across a field of tender yellow vegetation.

The distant hill is carpeted in dark viridian trees shaped like cotton balls.

Clearly something mysterious is happening. In the distance it is early summer, with an Italian azure sky and a late afternoon sun. The air is clear and sunny.

But the foreground is plunged in a mystical night.

The sun seems to be shining on the saint, because it casts strong shadows behind him.

Weaker shadows trail from his trellis, his walking stick, and the footrest of his table.

Yet just a few feet farther on there are no shadows. The saplings and briars bask in a shadowless haze. The donkey casts almost no shadow, and a big tree behind it is entirely shadowless.

Is the saint looking up at the sun? Possibly; his robe is warmed by an ochre light, and he even has a tiny yellow glint in his eye.

A bluish light lingers around his hermit's retreat like a toxic fog. Why doesn't the sunlight penetrate it? And what exactly is St. Francis looking at? His eyes are fixed somewhere up above the upper-left-hand corner of the painting.

In the corner itself, the clouds suddenly become sharp-edged and yellowish, and a laurel tree bends in a strange way, as if someone has jumped into it.

When I was young, I thought there must be a true miracle somewhere to the left of those bright clouds at the very far top left of the painting, out beyond the picture frame.

I thought the saint is experiencing something so tremendous that Bellini knew that he couldn't paint it. Looking at the picture was like looking at an eclipse by watching its image cast on a sidewalk. I saw the bluish rocks, the saint's astonished and serious face, and the uncanny light, but I wasn't allowed to see what he sees.

Then, some time when I was in my teens, I read the stories about St. Francis's stigmatization. According to one version, he had been meditating late at night, when a blinding light fell over the landscape. He turned toward the light, and was pierced by the stigmata--five wounds in imitation of Christ's punctured hands and feet and his cut side. Since the painting is called The Ecstasy of St. Francis, I looked for the wounds, and found two small ones on the saint's hands.

The painting is meant to show the moment of the stigmatization, but it does so with extraordinary subtlety. (The picture is currently titled St. Francis in the Desert, a title that omits the miracle completely. I would have preferred that when I was young.)

It is only nighttime in the front of the picture. (Some historians prefer to say that the entire picture is meant to be a night scene, despite what their eyes show them.) Heaven doesn't open up and spill out angels, and there are no streams of blood from St. Francis's wounds. I imagine most visitors to the Frick see it as a picture of a saint in a landscape, praying. You'd think that if the revelation had taken place at night, and a brilliant yellow light had shone on the saint, everyone in that distant village would have come running. It is a revelation, but it is exceedingly subtle, and only a few creatures take note of it.

The donkey's ears are pricked back and its mouth is slightly open as if it were dully aware something is happening.

Just under St. Francis's right hand, a rabbit peeks out of its burrow: it is alert, but wall-eyed, and its stare doesn't reveal what it sees.

At the far lower left, in a dark ravine, a small, dark, russet-throated bird looks skyward. It might be craning its neck to catch the water that drips from a stone spout, or it may be trying to see the miracle overhead.

In the far distance, the shepherd turns and looks our way.

And most subtle of all: toward the rear of the flock one ram is painted very carefully, and it stares right at St. Francis.

When I first saw how this worked, I was won over. Bellini must have been uncomfortable with the idea of a heaven populated by people in robes, and he kept the saint's supernatural bleeding to a minimum. He was uneasy, too, with the idea that the night sky could have been lit up by a miraculous searchlight. The painting shows how a miracle might look with the volume turned way down. It takes place on an almost ordinary mid-afternoon, and produces only a few spots of blood. There is no angel and no costume melodrama. Instead, the landscape is the miracle. Because nothing is quite what it should be, everything is partly sacred. The rocks and trees are nearly supernatural, so that the sky and the saint can be practically normal.

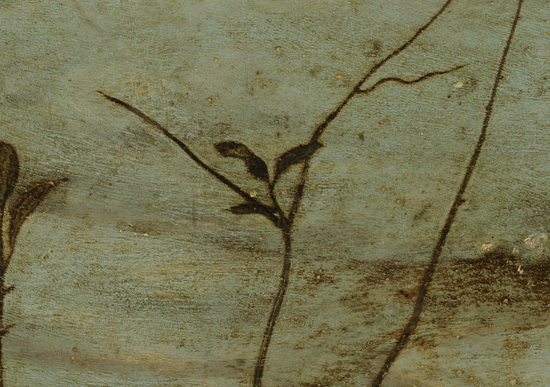

When I was young, visiting the painting, I looked especially long at the plants that sprout along the bottom margin of the painting. (They were easier to see because they were at my eye level.) In front of the saint's feet, for instance, there are four stray plants. Most artists would have painted a corsage of four stems, with leaves all around in a pretty circle. Bellini would never be happy with such a cliché.

The left-hand seedling has a straight stem, with one tiny leaf down low, and a crown of leaflets at the top. It isn't possible to tell how many, because he has let them rest on one another in a tangle.

The third sapling is a masterpiece: it wavers slightly on its way up, and then splits into two twigs. Three tiny bluish leaves nestle in the fork. Both forks are barren.

One shoots out to the side, and the other sprouts an oscillating tendril, and ends in an upward flourish. The wavering stem is an echo of the wavering laurel tree, on a scale so small it would never be noticed. (It is as if the little twig experiences another, smaller miracle of its own.)

The painting is replete with these miracles of close observation: each leaf is polished to a dark shine, each stone is enameled.

At the far upper right, three tiny tendrils hang down. The longest one, so thin it looks more like a blond hair, has four delicately lobed leaves hanging on bell-shaped stems.

It ends in diminutive leaves so tiny they escape into the surface of the painting.

All these things I've named are visible when you look at the painting. But there are many more tiny details in the painting that I have only found by looking at the Google Art Project image. Here are two. (I won't say where they are in the painting.)

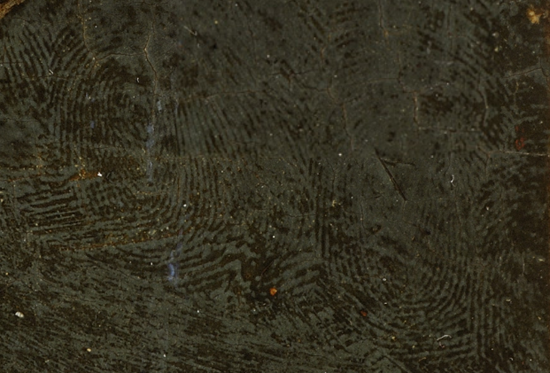

And most amazing, the Google Art Project shows the painting is apparently full of fingerprints:

But I won't show any more things like this, because I want to stay with things Bellini could plausibly have wanted people to see.

So, back to my theme. Like all great paintings, this one changed the way I saw real landscapes, and I started paying even more attention to the tints of rocks and the shapes of clouds. I noticed when a leaf was too tiny to notice, or when a stem deviated as if it were being pushed gently to one side. I watched the broken paths light follows as it finds its way through foliage to the ground. I would never have said it this way when I was young, but the painting was a kind of Bible without words: it taught me how to find meaning in the smallest scrap on the forest floor, or the dullest glint from a nameless stone. Many of the themes I will be writing about in this column, from moths' wings to ice halos, are things I might not have ever bothered to look at if I hadn't had the experience of looking at this painting.

That was then, and this is now. Now, I feel almost nothing for the picture. I can recapture part of what I once felt, but the intensity is gone, and so is my conviction. Once I was transfixed by a world where every ordinary object glinted in a fractionally sacred light. Now I can't quite see that: I have gone back and looked again, but it's not a transcendent painting any more. I can still see that Bellini labored over plants and stones, and sometimes I can almost picture why I spent so long in front of the painting almost thirty years ago. But the miracles have drained out of it.

I put the blame for this squarely at the feet of my own field, art history. My attraction to this painting was undoubtedly one of the reasons I eventually went on to study art history, and in particular Renaissance art. But as I read more about Bellini, and about the painting, I lost track of what I had felt before.

Next month I will describe what I learned that ruined the painting for me. (I am revisiting a chapter from a book of mine, so if you want to read ahead, you can find out.) The moral isn't to stay away from all scholarship, and just look without understanding. The moral is that no matter how amazing an artwork is, no matter how long you look at it, it can be wrecked by just a few pages of writing. Next month, I will finish this column with a discussion of the poison well of scholarship, and how it can corrode and dissolve the things you may love.