The way AJ Dimarucot tells it there is a clear date of copyright: July 16, 2008. That's the date that 'When Pandas Attack', created with collaborator, Jimi Benedict, won Tee of the Day on the Emptees T-shirt site. Dimarucot then submitted the design to Threadless where it's been a bestseller. And then in September of 2010, someone on Twitter told Dimarucot to check out an article in the New York times: it was a feature about Rob Pruitt's latest show, Pattern and Degradation, at Gavin Brown's gallery and it featured a painting with Dimarucot's snarling panda on it.

Miffed, the Threadless community organized a flash mob of supporters all wearing panda t-shirts and visited the gallery. Although they were encouraged to confront the artists and the gallery's management, the "mob" instead, posed for pictures, ate some candy, and left.

"Truthfully," says Parinaz Mogadassi, gallery director, "I thought they were a group of college students checking out the show. There wasn't an air of protest."

In the days following the impotent protest, the story would receive only perfunctory coverage and then die out. Why? Wasn't it a case of out and out piracy? And doesn't anybody care anymore?

The answer is probably close to 'no' for many reasons.

But the main one is that we are living and working and selling in an atmosphere where no one even knows what the rules are, and, even when they do, thwarting or enforcing those rules has become a game of wit and power. No one really cares about intellectual property unless they are losing money and the only people losing money are the ones who can't keep up in court.

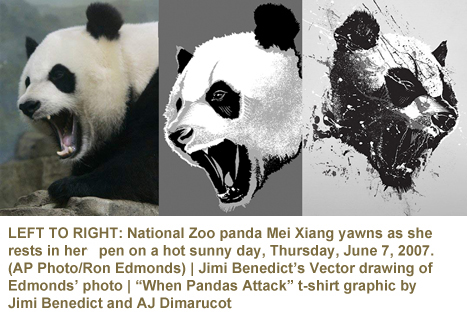

In point of fact, the real story begins before Dimarucot's copyright date. Someone took a picture of a snarling panda way before 'When Pandas Attack' was born. The photo is all over the internet with no credit line to be found. Jimi Benedict found it and produced a vector drawing of the photo and passed it along to A.J. Dimarucot who made the t-shirt graphic out of that. Then Pruitt took the t-shirt graphic and made a sort of quilt-like repeat for his own painting.

No one along the chain of creation sought permission. And, although the artists would likely beg to differ, an examination of the images shows small changes from one art object to the other, with the original composition shining through all of them. It is pretty clear that no one was covering his tracks.

So what's going on here? Balls out copyright infringement? Fair use?

It's always been a tough call; and, due to changes in the application of copyright laws, the growing archives of easily poached images online, and the renewed popularity of street art and representational imagery, it's an even tougher call now.

Is Copyright outdated?

Recent court decisions where "fair use" is invoked as a defense, seem to pivot on a rather fuzzy notion involving the amount of "transformation" (to be covered in next week's PART TWO of this article) given to any art object in order to make a new one. The new stress, which moves away from intellectual property and toward the formulation of terms for legitimate use, has made decisions regarding fair use ever more subjective. It seems entirely possible that in future, an increasing number of cases will be decided in favor of the defendants.

Because of this, growing numbers of artists and dealers have begun to regard the courts as a crap shoot and the notion of intellectual property as downright quaint.

Add to this the fact that, online image banks, like Creative Commons, with their ease of use, but complicated legal caveats, create a good deal of confusion about copyrights. Many graphic artists assume that any image they find there can be used without worries about licensing or permissions.

"And there are all sorts of urban myths about that, " says Lisa Shaftel, National Advocacy Committee Chair of the Graphic Artists Guild, "I've had artists and photographers argue with me that using some percentage of an image is OK. There's a myth in the music world that using less than 7 seconds is OK. There's also a myth in the literary world among writers that using only so many sentences or only a fraction of a sentence is OK. None of this is true, or established in copyright law."

Nevertheless, neither Benedict, nor Dimarucot have any qualms about their use of the bear photo. Says Dimarucot, "Personally, I use a lot of photography in my work and use those that have a Creative Commons license, with the license that states 'commercial purposes + modify, adapt, or build upon'. I also use public domain images. I know most artists reference art from somewhere, some just build upon the image more so than others. In our case, we used the panda as reference but completely transformed it into something else."

It may be that Dimarucot is usually careful about which images he uses, but neither he, nor Benedict, were able to tell me where the panda photo came from originally. This is why Shaftel warns against any degree of assumption, with the first rule of thumb, "When in doubt, ask first."

It seems, though, rather silly and arduous to play by such demanding rules when no one else is. Especially if one can simply push forward and pay (perhaps) later: this is why the big guns, the one's who will be called "appropriators" instead of 'plagiarists', have seemingly abandoned copyright law altogether.

In the current free-for-all atmosphere, it has become common practice to admit flat out to deliberately copying images line by shadow. Jeff Koons won against a lawsuit by photographer Andrea Blanch, even though he stated outright that he had "slavishly copied" from one of her photographs. Shepard Fairey made no bones about admitting that he used one of Mannie Garcia's many photos of Barak Obama in order to make his, now famous, HOPE poster. (He recently settled his case with the Associated Press, making a deal that involved promises of a future artistic collaboration with them.)

Enter Mr. Pruitt: although he does tell a rather unlikely story about how he found Benedict/Dimarucot image (stating that he took a snap of the t-shirt when he saw someone wearing it on the street) panda poacher, Rob Pruitt never bothered to deny that his snarling pandas were copied.

Nor does the artist's representation.

When confronted with Pruitt's unabashedly cribbed panda, the mighty Gavin Brown, of Gavin Brown's Enterprise, shrugged, "So what?"

"I don't believe in the ownership of ideas or creativity," he says, "To me it's one thing, made by all of us, something to be added to. Not protected by lawyers."

On Power and Powerlessness

When I first began corresponding with Gavin Brown, he accused me "perpetuating boring and outdated positions of power and powerlessness." Although he had my personal point of view completely wrong, he was not totally off the mark when it comes to how the story was spinning itself out online at the time.

Questions about the legitimacy of derivative images often move in and amongst three related categories: ethics, law, and aesthetics. Brown assumed that If I was examining Pruitt's use of the Benedict/Dimarucot graphic, I must be on the side of the kids who had recently flash mobbed Pruitt's Pattern and Degradation show at Gavin Brown's Enterprise (GBE) in protest over the use of the snarling panda image.

That is to say, he instantly placed my inquiry into the ethics category. And the ethical reverberations of this specific story were manifest online, mostly as outrage toward the powerful GBE and its championed pop artist, Rob Pruitt, for ruthlessly stealing the assumedly sweaty efforts of two powerless graphic artists and a t-shirt manufacturer.

It's one point of view. And not entirely illegitimate.

When Hyperallergic published its ironic 2010 List of the 20 Most Powerless People in the Art World (a satiric play off ArtInfo's Power 100), 'Copyright' made number 2. "It's over," they wrote, "Just accept it and stop hoarding."

Joking though they may have been, the editors at Hyperallergic were echoing exactly the sentiment of Gavin Brown. It's in the air: is intellectual property going the way of the ether?

It's looking like it. On the same Powerless 20 list, "Graphic Designers" had the honor of making number nine. Quipped the editors, "Artists like Rob Pruitt don't consider you worthy of recognition, hell, he probably doesn't even think you're artists. It's the reason why he ripped one of you guys off for his recent panda paintings at Gavin Brown. Yeah, we know, he's a douchebag, but he's not on this list so he's a powerful douchebag."

The list stands as a counter balance to ArtReview's 2010 Power 100, which, by the way, lists Gavin Brown at number 30, stating, "Brown's gang contains more than a few cool kids: Rob Pruitt, Rirkrit Tiravanija, Mark Leckey and Martin Creed, among others."

Douchebag or cool kid, it goes without saying that Pruitt is in a good position to defend himself against piddling copyright infringement lawsuits by pesky t-shirt designers and manufacturers. Championed by Gavin Brown (speculated to be New York's next Jeffrey Deitch) and powered by a reputation for mischief that harkens back to some notorious and mythologizing missteps, bolstered by the recent fame and popularity garnered from two successful Rob Pruitt Art Awards ceremonies (last year and this one), Pruitt has every kind of support; money, influence, popularity: copyright has no power over him.

Certainly AJ Dimarucot recognized this as soon as he even entertained the notion of suing.

"The issue," he says, "is the price. Since I didn't register it before the infringement. Which apparently means the lawyer can't waive attorney fees and will have to charge hourly. If I had registered it before the infringement, we could've sued him without paying legal fees outright--the lawyer would've been paid for his services if Rob settles."

What's more, he says, the manufacturer and distributor of the T-shirts, the crowd-sourced online shop, Threadless, told him that "they can't pursue the case legally because they only have rights for usage on apparel. If Rob printed on t-shirts they could pursue."

Asked about his reaction to Pruitt's use of the Jimiyo, Dimarucot design, Jake Nickell, Founder and CSO for Threadless said, "So far, our reaction to the issue has been staging the "flash mob" in NYC. We wanted to bring awareness to the issue but didn't feel like we should take it as far as going to court over it. We didn't find it in our best interest to allocate the time/money/resources necessary to do so."

Case closed: the Power 100 wins.

It seems too easy, almost cynical, to claim that intellectual property is passé and copyright laws, misguided, when you stand to win most disputes and when losing them doesn't upset your bottom line.

And there is a degree of hypocrisy involved when those who "appropriate" seek control over their own art objects and wield a body of lawyers to do so. Jeff Koon's lawyers have issued a cease-and-desist letter to Park Life store and gallery, demanding that they stop all sales of their balloon dog bookends. And renowned stenciler, Shepard Fairey took similar action against Baxter Orr, a young designer who created some limited edition prints that parodied Fairey's Andre the Giant face.

I asked Gavin Brown about whether or not GBE would sue if an artist took Pruitt's panda repeat and used it as an all-over pattern for a t-shirt. He never responded.

And, it is notable that when Brown was asked by the Guardian to comment on artist Stephanie Syjuco who had set up a booth ( Copystand: An Autonomous Manufacturing Zone) at Frieze Art Fair in 2009, wherein she sold cheap replicas of works from other exhibitor's booths, including Brown's, his response was less than enthusiastic, "I have no reaction. And that is a reaction in itself. My reaction is flat." I'd have expected some support from a fellow fan of appropriation but, apparently it's not appealing when the appropriator is not yourself.

The fact is that there is still a lot at stake in intellectual property. Powerful or powerless, artists and dealers (or manufacturers) do make money from the objects they make and sell. It might seem like a pretty good idea to surrender the ghostly essence of owned ideas and throw it all in one big communal pot, but when it comes down to the question of who's making money from who's efforts, we all chaff. There are yet too many questions about how that utopian market of ides would work: and who it would work for.

NEXT WEEK: Part TWO: Appropriation: The Game (Aesthetics & The Law)