Co-authored with David Walker

On November 6, 2012, voters in Washington and Colorado voted to support what was previously considered a radical experiment in social policy: the legalization of marijuana. More recently, Oregon, Washington DC and Alaska joined these two pioneering states. Though 23 states have legalized medical marijuana, the ballot victories in Colorado and Washington broke a long string of losses for full legalization efforts at the ballot box, including the prominent failure in 2010 of Proposition 19 in California.

What changed to break the pattern? The key was the ability to convince voters who haven't used and don't like marijuana to support legalization.

For a variety of clients, we have conducted research on marijuana reform in 10 states, including survey work, focus groups (online and in-person), online ad testing, modeling, a longitudinal review of public data, and an analysis of previous marijuana reform, and we were the pollsters for the victorious Initiative 502 campaign in Washington. This depth of research afforded us a front-row seat to this broad social change and gives us some perspective on how this movement might evolve in the near-future.

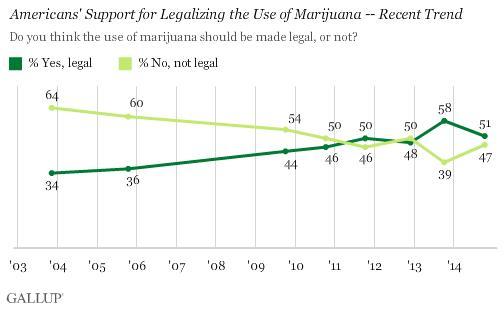

The wins in Colorado and Washington represent the fruit of a broad national evolution on this issue. A majority of American voters now support full legalization. This movement does not result simply from the rise of the millennial generation, which is more favorable towards reform. Support for legalization is highly correlated with age, with support dropping off dramatically among older Silent Generation voters who, unlike Boomers and their children, did not experiment with this drug. However, both the scale and the pace of change nationally--nearly 50 points net -- make it obvious that generational replacement alone cannot fully account for the new, pro-legalization majority.

Indeed, our own analysis of the American Community Survey (ACS) data shows that, even before 2012, voter opinion was changing within generations and even among seniors.

The change in public opinion does not necessarily reflect some newfound public support for marijuana use. Gallup shows that the number of people who have tried marijuana (38 percent, self-ascribed) has remained stable since the 1980s, even as support for legalization has doubled.

While voters' perceptions of marijuana have progressed from the "Reefer Madness" government propaganda, and many voters concede marijuana is less dangerous than other drugs, including alcohol, the fact is 51 percent still describe marijuana as a serious problem, 50 percent describe marijuana physically addictive and 47 percent believe it is a gateway drug.

The rise in support for legalization, rather, reflects the growing consensus among voters that the War on Drugs failed, and that the cost of prohibition exceeds purported benefits. Because of the cost to both society -- in terms of criminalizing behavior that 38 percent admit to -- and to law enforcement -- in terms of police and prosecutors exhausting resources enforcing marijuana laws -- voters recognized the perverse impact of marijuana prohibition: it increases crime, rather than reduces crime. By controlling and regulating the marijuana trade, legalization could not only destroy the criminality inherent in the black market, but also free up law enforcement to focus on more serious, violent crimes.

As important, voters also came to see the careful, controlled regulation of marijuana as an important source of revenue. The timing of the successful referenda is notable. In 2012, state and local budgets were still reeled from the financial crash of the 2008 and subsequent recession. In the 2012 budget, Colorado reduced state aid to K-12 education by $250 million dollars and to higher education by $36 million. Likewise, Washington State faced a one billion dollar budget short-fall. As voters concluded the War on Drugs failed to seriously curtail marijuana use, that some people would consume marijuana regardless of the law, the notion of finding some societal gain from that activity, specifically additional funding for education and other state priorities in tight budget times, found traction.

Both of these arguments gave voters who do not use or do not like marijuana a reason to vote for legalization.

These two themes -- that marijuana legalization could reduce crime by destroying the black market and releasing law enforcement to pursue more serious criminals, and that legalization could raise millions of dollars in tax revenue for schools and other social goods -- would play a defining role in the legalization efforts in both Washington and Colorado. In ads sponsored by New Approach Washington, the group that drove the legalization effort in Washington, figures from law enforcement argued the case that legalization could reduce crime.

Ordinary voters like a Washington mother argued in an ad that while they didn't like marijuana, they understood the system was broken and that a "tightly regulated" regime could not just reduce the problem, but also bring the state needed revenue. The innovation was to frame the case for legalization from a conservative standpoint.

There is no question this success will fuel legalization efforts in other states. California in 2016 certainly looms large, given the size and the cultural influence of that state. The real question is whether legalization efforts can also break out in more conservative, red or purple states. Support for legalization in national surveys peaked at 58 percent in Gallup in 2013, just after the victories in Washington and Colorado, and now hover around 50 percent. Some ebb and flow is to be expected, even while the overall trajectory remains favorable.

Two dynamics are worth considering:

First, the current national conversation around social justice and over-policing could play an outsized role in future legalization campaigns. This conversation emerged from incidents of police violence, not legalization efforts, but the overlapping framework of a legal regime that severely and asymmetrically punishes some "crimes" is obvious. A social justice argument can potentially find new supporters in communities of color.

Second, before 2012, marijuana legalization, at least in the United States, was a social theory. Both sides made arguments about what would happen, but it was all conjecture. In at least four states it is now a reality. Both supporters and opponents will comb through the data in Colorado, Washington, Alaska and Oregon looking at crime figures, graduation rates, marijuana use, hard drug use, revenue and the like to make their arguments. The actual experience of marijuana legalization will likely make a more powerful argument than prospective arguments used in the past campaign. Indeed, a new study published in The Lancet Psychiatry that covered a 24-year period and is based on surveys of more than one million young people shows that states that passed medical marijuana laws did not experience an increase in teenage marijuana use.

How these dynamics play out in the near-future is difficult to predict, but progress on this issue seems more likely than not. In the fight for marriage equality, marriage became legal initially in just a handful of states. Voters noticed that, somehow, the earth did not stop spinning, and equality snowballed from there. This issue appears to be on a similar path.

David Walker is a vice president at Greenberg Quinlan Rosner Research