What is it like to be childless as a Jew, when the very first Jewish commandment is to be fruitful and multiply (Genesis 1:28) and scripture likens the childless to the dead? What is it like to be childless in Israel, a country that values children above all, as a supreme value? These are just some of the questions Elliot Jager addresses in a brave new book, The Pater: My Father, My Judaism, My Childlessness.

Jager frames these questions from his perspective as having been abandoned as a young child by his father--the "Pater" as Jager has come to call him in his mind. What does it mean to be a father, he ponders. Was he robbed of a chance to prove himself a better man, a better father? Would he have been a better parent than his own father?

But Jager also addresses these questions from a religious standpoint, having removed his skullcap at a certain point along the way, deciding his orthodoxy was a sham and possibly angry at God for not granting him the ability to procreate.

In order to make his story appeal to a broader audience, Jager interviews other childless men and discovers that no two journeys into childlessness are alike, though some general conclusions can be drawn. The author includes these interviews out of concern the book is more about Jager than about Jager's childlessness; that the reader won't want to read his story as an autobiography so much as a way to glean helpful information about being childless and owning that status with grace. Therefore Jager talks to other childless men. But it seems to this reader that Jager accomplishes all his aims. The book is interesting and poignant as an autobiography and an accounting of his experiences while remaining relevant to others who remain childless either by choice or Divine design.

The Pater is, in any event, exquisitely well-written by any measure. Perhaps that is because Jager comes with years of experience as an editor at the Jerusalem Post. In fact, it was Jager who let me know my first op-ed ever had been accepted. Two weeks had gone by and I had given up hope when one day I found his email, "We like your piece," he said.

I never forgot that moment.

And so perhaps I was kindly disposed to Jager the author, because I was kindly disposed to Jager to editor, but I don't think so. His writing is just superb. Take the breathtaking ending of Jager's prologue, for instance:

"Like some kind of metaphysical fog, the reality of my childlessness lightly blankets my soul. On a sunny day it gets burned off by life's routine. It doesn't hang oppressively, incessantly, unremittingly over my being.

"And yet it changes everything."

Throughout the book, Jager is as honest as he needs to be, as someone exploring what it feels like to be odd man out, someone perhaps punitively fingered by God and marked within his own community. Honest as he is, Jager doesn't go sappy on us, or say things that are not necessary to the story, simply because they might add shock value. He intimates at times, and the reader understands what he is not saying. Jager is a gentleman and it comes across on every page.

The reader learns some devastating and disturbing statistics. Seventy-five percent of Israeli IVF attempts, for instance, fail. "There are no empty picture frames in IVF clinic waiting rooms for all the babies that didn't get made," writes Jager, and the reader knows the sad scar on his soul, on his wife Lisa's soul, with poignant immediacy.

The author gives us a window into his deep love for his wife. He hadn't been so sure about wanting to be a father but, Jager explains, "The more confident I felt in my marriage, and the more I came to realize how much Lisa wanted to be a mother, the more important the idea of children became to me. Like the patriarchs before me, I wanted to see her wish granted."

We hear of his loneliness, having no one to talk to about being childless, his isolation. Many of the men Jager interviewed felt the same sense of being alone, being different, being unmanned somehow, and how no one in their circles quite knew what to do with them. Then there is Jager's deep and thoughtful reading on the subject. From Liberty Barnes, who wrote a blurb for the book's back cover, "Infertility is not life-threatening, but it is life-defining."

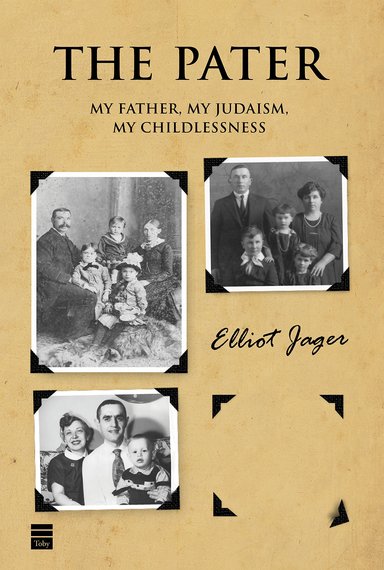

Author Elliot Jager

Sometimes I had no patience for Jager's religious questions. I wanted to tell him that he was using his childlessness as a reason to shun God, but that it was just an excuse. I held my tongue, because I could see that Jager is really trying to come to some kind of understanding about God, an accommodation, and that his shrugging off orthodoxy stems from a much earlier time, really. Accepting childlessness simply freed him to come out of the closet religiously, so to speak.

I enjoyed reading about that journey, too. The way, for instance, Jager cites contemporary wise men such as Aryeh Cohen, associate professor of rabbinic literature at California's Ziegler School of Rabbinic Studies on how to wrestle with "divinely inspired texts," that as Cohen says, "jar our moral equilibrium." Clearly, Jager didn't just wake up one day and decide to blow off religion (and anyway, he's not blowing off religion per say, but only orthodoxy). This is a man who thinks deeply, and tries hard to find a way to understand what confuses and pains him. "If you don't grapple with theodicy--reconciling God in a world where God is omnipotent--can you even have a relationship with God?" wonders Jager.

Of all the childless men the author interviews, I found myself most enchanted by Hezie, a deceptively simple-seeming Sephardic man, whose faith in God is natural and boundless. Of Hezie, who bristles when Jager describes him as performing Tikkun Olam, the author writes, "He doesn't like anything that smacks of political correctness. 'We Sephardim do it anyway as a way of life,' [Hezie] says."

Ashkenazi Blinders

Hezie tells Jager he's over-thinking the issue of childlessness, coming at it with "Ashkenazi blinders." (I would have done the same as Jager, but then I too, am Ashkenazi: guilty as charged.) The interview with Hezie ends with hope. "You know what? I like it that way," says Hezie on remaining hopeful. "I also like a good cry every now and then."

From a personal standpoint, there is something truly terrible about reading Jager's book as a mother of 12 children. Do I have the right to review his book, as someone so far on the other side of the equation--so far from the experience of childlessness, I wondered. And yet, even I learned something from Jager's journey, and related to some of the advice he received, in particular from Rabbi Joseph Isaac Lifshitz. Lifshitz speaks of procreation as the easy way to give back to the world, to be productive, as a form of imitatio Dei, Imitating God. "The simplest creation that man can do is having children. It's amazing, effortless for most. You don't have to be too intelligent to procreate. And it's not your fault if you don't," explains Lifshitz.

This is something I have always felt to be true. I never felt I deserved any special congratulations for having lots of children. I like the way Rabbi Lifshitz counseled Jager. Everything he said hit the right notes.

Resolution?

At a certain point, the book seemed too depressing to me, and I worried I wouldn't be able to finish it. I put it aside for a week, but then felt compelled to try again. The words in this book were too important to be shunted aside for making me sad. Jager, and the men he interviews, deserve to be heard. Also, I hoped the author might speak of resolution in the final pages of the book.

He did.

Jager concludes by telling us how his relationship with his father has mellowed, how he has somewhat come to terms with God and with childlessness, and how satisfied he is with Lisa as his wife. I was left feeling that this is an important book as a record of one man's struggle with his history and with his childlessness, but also as an important book for any couple struggling to be reconciled with childlessness. I would even dare suggest that perhaps God in his wisdom, preferred Elliot to produce this exquisite volume as his greatest legacy to the world at large.