Last week's ambush and murder of a campus police officer at Virginia Tech naturally evokes memories of the horrific massacre at Virginia Tech four and a half years ago. Another shocking killing -- one that happened in 1840 -- sheds further light on how to understand campus shootings.

For several years at the University of Virginia, students had an annual tradition of raising hell around campus, burning tar barrels and shooting pistols into the air. The rioters wanted the freedom to carry arms on campus and each year marked the anniversary when restrictions were put into place that resulted in some defiant students being expelled. On November 12, 1840, the dean of the faculty, law professor John Davis, heard gunfire and stepped onto the porch of his pavilion, one of the on-campus residences of the UVA professors. Discovering a masked student, Davis pursued, tried unmasking him, then gave up. As he turned to walk home, he was shot. After two days during which doctors tried and failed to remove the bullet, Davis died, survived by his wife and seven children.

Portrait of victim Professor John Davis

My new ebook novella dramatizing this largely forgotten incident, The Professor's Assassin, condenses some of the events for storytelling purposes, but the impact and drama come straight out of the history. Professor Davis was popular with students and faculty alike at the university chartered by Thomas Jefferson twenty one years earlier. Davis had actually advocated leniency toward rioters, allowing previously expelled students to "make application for readmission, on their disclaiming participation in the principal acts of riot and violence which had been committed, or, if they could not do so, on their making proper atonement." Davis, on his deathbed, refused to name his assailant. How he knew the shooter's identity in the first place is not clear -- whether he had recognized the voice of the gunman or some distinctive article of clothing, or perhaps saw the student's face when he grabbed for his mask.

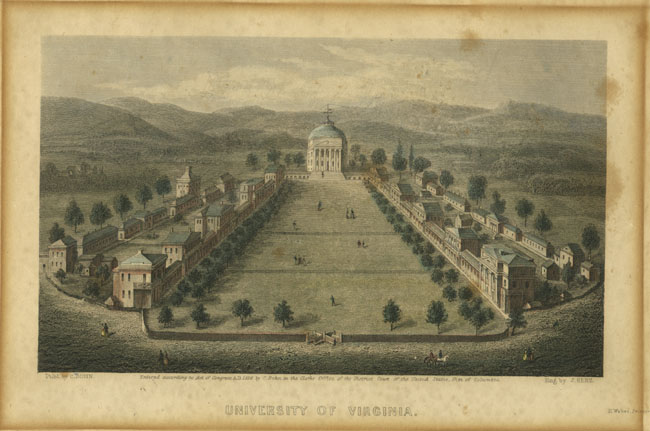

Pavilion X, outside of which Davis was ambushed and shot down, is shown here in the foreground, on the right

During an earlier outbreak of student violence, William Barton Rogers, the future founder of MIT who at this time taught natural history at UVA, wrote "our police is worthless." Without Davis's cooperation before he died (his wife likewise refused to name the assailant), the faculty and even the students took active roles in the investigation, some being deputized for the purpose. The culprit must have been aware of the lack of investigative skill and authority around him, because he actually remained on campus until the clues piled up against him. In spite of the gravity of the crime, the suspect, eighteen-year-old Joseph Semmes, a member of a wealthy Georgia family, was permitted to post $25,000 bail (an enormous amount at the time). Semmes skipped bail and there was never a trial. This left a strong sense that consequences could be avoided by "money and influence triumph[ing] over law," as one of the students remarked who had helped identify and capture Semmes.

Even without a trial, the historical record provides some insights into the shooter's motive and into the general ethos that led to the tragedy. There did not appear to be any particular animus on the part of Semmes against Davis. On the night of the shooting Semmes told a classmate that he would shoot any professor who tried to interfere with their rioting. It is worth remembering not only that many of the students at UVA at this time came from wealthy slaveholding families, but also that they were served at the university by slaves, who were subject to abuse and violence at the hands of the students. We can detect an era in which student populations found it distasteful to submit themselves to any authority. Edgar Allan Poe, an earlier UVA student, once complained in a letter that his stepfather spoke to him as if Poe were one of the black slaves; some of the students at UVA surely felt the same about being told what to do by faculty. Accustomed to using violence to handle their own servants, many of the well-armed young adults were one provocation away from turning violent against their professors. In one instance when UVA students were beating a slave and a professor tried to intervene, he was physically restrained because, as one of the students said, "any man who would protect a negro... is no better than a negro himself."

Today, latent forms of violence seep into the youth culture less directly than the brute violence that came with slavery -- first person "shooter" video games, for example, have allowed easy simulations of desensitized killing. But most powerful, perhaps, have been the examples of other shootings and the consumption of details made available through the media coverage. After Joseph Semmes vanished from the public, the story of the assassination of his professor mostly vanished, too. After all, it was not in the interest of the university nor the students to dwell on what had happened. The intense media coverage of today's campus shootings presents a double edged sword. On the one hand, it gives us a chance to think about and reflect on the causes; on the other hand, in a very small minority of unstable minds the repeated telling of the stories can be interpreted as glamorous. We do not yet know what factors drove the latest Virginia shooter, 22-year-old Ross Ashley, to murder. But Seung-Hui Cho, who terrorized Virginia Tech in 2007 and killed 32 people, was reportedly obsessed by the Columbine massacre in 1999 and aspired to "repeat" it. Likewise, when Ashley fired his weapon and sent the campus into chaos, members of the community understandably reported thinking, "not again!"

Not again: both a lament and a rallying cry repeated long before our own time.