The agency doors are open and Washington has returned to a more normal state of dysfunction. What has 16 days of darkened offices, empty parks, and a powered off panda cam cost?

Putting politics aside - it's obvious Republicans paid dearly - there are a number of possible answers. The most narrow is the federal budget cost, which probably will fall in the range of $2 to $3 billion. The Office of Management and Budget put the cost of the 1995-96 closures at $1.4 billion; time has likely raised the cost somewhat.

A broader answer would include the loss and degradation of federal services. Parks were closed and refund checks will be delayed. And you should probably tally as well the stain on the U.S. reputation in the eyes of the world. All of which raise the sticker price.

However, a really substantial price tag comes solely from economic damage - lost jobs, less hiring, reduced paychecks, and foregone investments. On this front, at least, the White House has its mind made up, asserting "The government shutdown and debt limit brinksmanship have had a substantial negative impact on the economy."

Perhaps. But let's think this through. Some spending does not change. When the government shuts down, employees and suppliers get paid - just later. Moreover, in this instance Congress quickly assured workers that checks would be issued. If everyone has enough liquidity to handle the interruptions in cash flow, this should have zero impact on spending. The same total checks will be received; only the timing is affected.

Some spending gets shifted across the economy. Instead of heading to the wilderness area and paying for concessions and horseback rides, the family ends up at the mall paying for movies and popcorn. One sector wins at another's expense.

Some spending gets shifted over time. Not every worker has a lot of cash sitting around; if so they may cut back temporarily, but are likely to turn around and buy the new washing machine they need when the back pay is issued. In this case, real economic activity - spending - is temporarily depressed during the 16 days, but rebounds thereafter. Most likely, the average impact over a month, and certainly a quarter, is zero.

Spending unchanged, spending shifted to different purchases, and spending shifted later in the year. The mechanics of shutdown suggest that there will be few absolute losses. Mechanics are one thing; psychology is another.

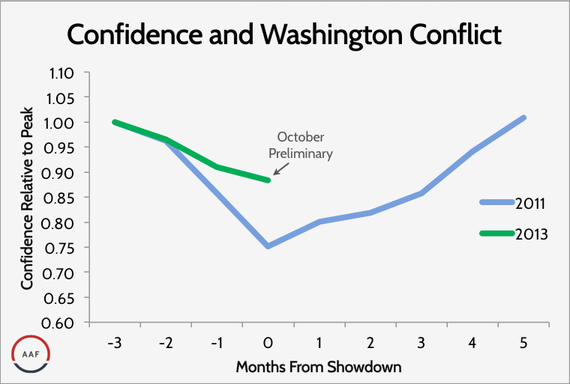

To see this, consider the chart of consumer confidence. The blue line shows confidence surrounding the debt ceiling fight in August 2011. Specifically, confidence peaked in May - three months prior to the showdown - began to tail off as the partisan dispute escalated, and plummeted to roughly 25 percent below peak during the August showdown itself. In the end, it took another five months for confidence to return to May's peak level.

Importantly, in 2011 there was no government shutdown, no mechanical disruptions of cash flows from the government, and no loss of federal services. Instead the impacts were purely psychological, and they proved to be substantial. Economic growth decelerated; 3rd quarter GDP growth was 1.4 percent, down from 3.2 percent in the 2nd quarter.

The ultimate question now that the government is back open and the debt ceiling has risen is, will this happen again? We will get a clue tomorrow when the data on the University of Michigan consumer sentiment is released. As the chart indicates, consumer sentiment dropped from its recent peak in July, falling 10 percent by September. The preliminary reading for October showed another modest deterioration in optimism. If this is revised sharply downward, there will be cause for concern.

It would also be a warning to all sides that the economy may not be able to withstand a rerun of recent events when government funding runs out in January and the government bumps up against the debt limit in February. The largest fallout of Washington conflict is damaged consumer confidence.