One of the most prevalent talking points in the 2016 election cycle is the role of religion, and the in-grouping and outgrouping that political figures are using to describe America.

While Donald Trump's comments about banning Muslims from entering the country have drawn the most criticism, the racializing of Islam has been in full effect for well over a decade. This racialization has also dovetailed with American ideological polarization, making Islam -- and the role of Muslim-Americans -- a combustible topic of discussion.

What activists now call Islamophobia reflects a trend of outgrouping and Othering religions and cultures that are deemed incompatible with amorphously defined American values. As noted scholar Khyati Joshi has written about extensively, racializing religions such as Islam, Hinduism and Sikhism has also created an environment where Christian privilege is frequently assumed and subsequently imposed upon the public sphere.

But the racialization of minority religions began long before Islamophobia. In fact, prior to the 1980s (which saw the Iran-Iraq war, the U.S. backed-mujahadeen in Afghanistan, the first Palestinian intifada, and Islamic clerics' death threats against author Salman Rushdie over the Satanic Verses), Islam was relatively benign within the scale of America's religious and social discourse.

Compared to the pervasive anti-Semitism in American social discourse throughout the 20th century, Islam wasn't vilified as much as it was marginalized and exoticized -- primarily in the minds of Hollywood producers who viewed Muslims as harem-holding turbaned sheikhs or belly dancers. Ironically, Islam was seen as a positive force against the "darkness" of the Axis powers, highlighted by Frank Capra's reference to the Quran in the famous World War II propaganda film, Why We Fight.

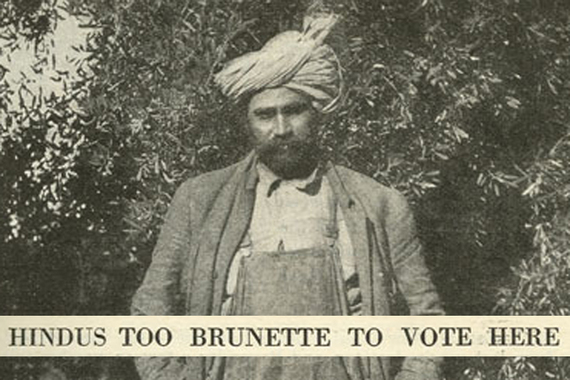

Instead, the racialization of religion in the American imagination -- and the creation of a permanent Other that continues to this day -- was the way Hinduism and "Hindoos" were represented. For starters, "Hindoos" was a term to describe anyone from India, meaning that many of those labeled as such in America weren't necessarily Hindu. The majority of "Hindoos" were in fact Sikh, though smaller numbers of Hindus and Muslims were part of the racialized, vilified, and attacked Indian community in the Pacific Northwest during the late 19th and early 20th century. Most of the victims of the infamous anti-Hindoo riots of 1907 in Washington state were Sikhs, though at the time, many Sikhs in America also self-identified as Hindus/Hindoos.

Even while Americans couldn't tell the difference among "Hindoos," Hinduism found itself in the crosshairs of American journalists, academics, cultural producers, and social activists whose interest were based upon fascination, disgust, the need to save, or a combination of all of the above. But ideologically, both liberals and conservatives believed that Hindus (and "Hindoos") were incompatible with America.

The 1923 U.S. Supreme Court case United States vs. Bhagat Singh Thind effectively racialized religion and ethnicity by denying Thind the same racial privileges as a white person. Thind (a Sikh who preached a unique blend of spirituality that drew from Hinduism, Sikhism, and Christianity to American audiences), in arguing for his U.S. citizenship, claimed his status as a "high caste Hindu of full Indian blood" qualified him for naturalization as a "free white person." The Court disagreed and nullified his naturalization, which also led to the citizenship revocation of A.K. Mozumdar, an Indian-born Hindu associated with the International New Thought Alliance.

Even as the Court racialized religious identities, the image of "Hindoos" as mystical and menacing became etched into American culture. Films like D.W. Griffith's The Hindoo Dagger (which he directed before The Birth of a Nation) portrayed Hinduism as an occult and a tradition of Black magic, while Katherine Mayo's 1927 book Mother India passionately argued that Hindu Indians were unfit were self-governance based on their "depravity."

Similarly, Indology in the early 20th century -- and into modern times -- framed Hinduism as incompatible with modernity, and as scholars Vishwa Adluri and Joydeep Bagchee write in The Nay Science, Indologists also projected their anti-Semitism onto Hindus. They wrote that Indologists' "Brahmans were creatures of their own imagination, caricatures of rabbis drawn with brown chalk."

Even after racial "Hindoos" became Hindus (and Muslims and Sikhs), especially after the Asian Exclusion Act was lifted in 1965, Hinduism continued to be viewed as a racialized Other, foreign to the American imagination when it came to spirituality and the idea of religion. As such, Hindus continue to be viewed from a lens in which their Americanness is often placed at odds with their Hinduness. Hinduism is still largely racialized, seen as more of an Indian/immigrant religion (which is quite prominent in school textbook descriptions) than one that has been a (largely unrecognized) part of American society for more than two centuries, including Transcendentalism, the influence of ahimsa on Martin Luther King, Jr. and Cesar Chavez, and the spread of yoga.

All of this is to say that race and religion remain volatile factors in the American public sphere. When they're combined, the combustible alchemy can leave some religious groups permanently on the margins. Even while conservatives rail against "radical Islam" and liberals pat themselves on the back for being more inclusive towards Muslims, these ideological debates miss the mark on how race and religion are weighed in the public sphere.

It might be worth noting that true inclusiveness means eliminating the rhetorical walls that arbitrate which religions are mainstream and which ones are Othered. This might involve critical gatekeepers such as the media and the academy being reflexive enough to see how religions are scaled, and how those scales of privilege determine access into the public sphere. Such reflexivity would aid in undoing decades of racial exclusion that has left religions like Hinduism caricatured in the American social fabric, and groups such as Hindus on the outside looking in.