I've always wanted to bury a time capsule. I want to fill a box with all of the things I find important in this moment and I want the person who unearths my time capsule fifty years from now to think about two questions: why did I group certain things together and what changed since I buried the box? If I made a time capsule today, I would include #BlackLivesMatter and #MarriageEquality in my container.

These movements represent another round of struggles with the parameters of inclusion and belonging in the United States. They challenge limited notions of equality by asking, equality for whom and equality of what. And they remind me of another time capsule from fifty years earlier that has important connections to the Marriage Equality and Black Lives Matter movements of today.

In this rusty old capsule, I uncovered the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-II (DSM-II) from the late 1960s. The DSM is psychiatry's handy guidebook for deciding which behaviors are considered normal and which ones are pathological. In this edition of the DSM, a new category of schizophrenia, a "protest psychosis," that disproportionately afflicted black men was included. In 1968, prominent psychiatrists, Walter Bromberg and Frank Simon, believed that "the stress of asserting civil rights in the United States these past ten years," was the cause of the illness. In contrast, within the same manual, "homosexuality" was removed as a disease. Gay activists borrowed tactics used by Civil Rights protestors to force psychiatrists to recognize homosexuality as a normal variant of sexuality. Protesting clearly yielded different outcomes for different populations.

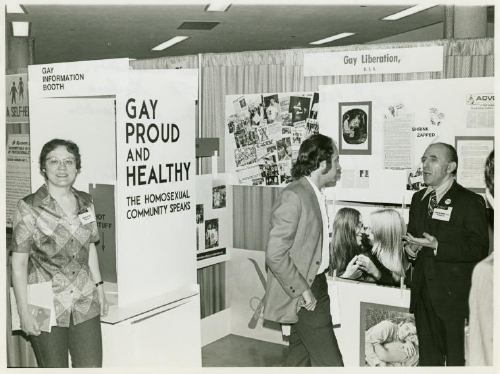

Gay activists who organized to depathologize homosexuality were predominantly white, male, able-bodied, middle-class professionals, invested in typical family structures. Their major deviation from the American norm was their sexuality and they used their social, political, and financial resources to fight for normal status. These activists demanded symbolic inclusion. They wanted the broader public to acknowledge that homosexuality was not a disease and identified psychiatry as an important gatekeeper for their goal. At the 1973 American Psychiatric Association meeting, activists' disruptions, protests, campaigns, and sit-ins all paid off. Psychiatrists voted to remove homosexuality from the list of mental disorders. To be gay was no longer a pathological condition.

In contrast, to be a black man engaged in Civil Rights protest, who "state[s] an objection to the accepted superiority of 'white' values," this was interpreted as a mark of a diseased mind. There was a new variant of schizophrenia published in the DSM-II that included hostility, violence, and aggression and this diagnosis was given to more black men than any other group. Historian, Jonathan Metzl explained that the increase in black men with schizophrenia was not an organic, biological process. Black men suffered from schizophrenia because their actions were now read through a certain racialized, diagnostic lens that reflected larger social and cultural anxieties.

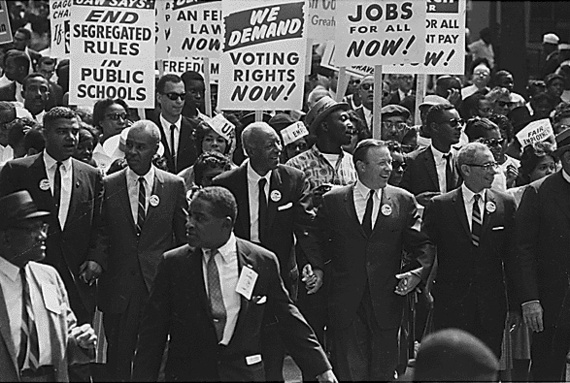

Black activists protested for employment opportunities, voting rights, desegregated schools and fair housing, amongst other things. They made tangible, material demands on society, rather than symbolic demands of inclusion. They challenged the existing power structures and were discredited with a medical diagnosis and relegated to life in asylums. Psychiatrists considered their particular form of protest outside of the realm of normal. This diagnostic legacy continues into our present day with black men receiving this diagnosis four times more often than is statistically expected in the population.

Comparing the DSM-II time capsule with the one I'm creating now, I am struck by how much has remained the same in the past fifty years. I find a gay activist movement that has a direct historical lineage from the DSM-II fights to #MarriageEquality. I see a successful, white, middle class, well-funded community that has been given access to "dignity" by being included in the folds of mainstream American society. And I am witnessing another moment of symbolic inclusion of a particular non-threatening group of individuals, without attention to the material struggles of those in the broader LGBTQ community. As this group vocally and exuberantly celebrates a victory, my thoughts are drawn to those who have less to celebrate.

The black men who protested their way into the DSM-II were the harbingers of #BlackLivesMatter. In this current black protest movement, I trace a continuation of a vital politics that asserts that black lives have a right to existence. I see a movement repeatedly silenced by tear gas and police batons, just as a mental illness diagnosis was used as a social tranquilizer fifty years earlier. And I fear this inevitable conclusion -- dominant power structures will continue to ignore the demands of the black community through inadequate medical care, or incarceration, or substandard housing practices.

While I don't believe that the success of one movement has directly caused the failure of the other, I do think that studying them side by side, historically and contemporarily, reveals some telling truths about the limits of inclusion and exclusion in this country. As I seal my time capsule, preserving this moment for future historians to analyze, I sincerely hope that the person who opens my rusty box fifty years from now will be shocked by the contents. I hope this person feels disbelief at the fact that in 2015, black people still had to assert that their lives mattered and that anti-discrimination legislation aimed to dignify all members of the LGBTQ community was not yet the law of the land.