BY MICHAEL INMAN, Curator of Rare Books at The New York Public Library

The torpedoing of the British passenger liner RMS Lusitania, which occurred 100 years ago today, was one of a series of traumatic events that eventually led the United States into World War 1. In the following piece, Michael Inman, curator of The New York Public Library's current exhibition, Over Here: WWI and the Fight for the American Mind (July 28, 2014 - August 16, 2015), examines the development, reception, and legacy of cartoonist Winsor McCay's pioneering animated propaganda movie, The Sinking of the Lusitania, released in 1918. It was during World War 1 that motion pictures were first used on a large scale as propaganda vehicles.

America, 1915

More than any other single event, Germany's sinking of the Lusitania on May 7, 1915, which resulted in the loss of 128 American lives, signaled the moment when U.S. public opinion about the First World War began to crystallize. Suddenly, if only in a limited fashion, the nation's connection to the far-off "European War" became impossible to ignore.

Prior to the Lusitania disaster, the country's relationship with the conflict had been characterized largely by ambivalence. Most Americans were only too happy to hold to President Woodrow Wilson's dictate that they should remain "impartial in thought as well as in action." There were, of course, exceptions. Widespread media accounts of atrocities committed by the German army during the summer and autumn of 1914 had already begun to align numerous Americans' sympathies with the Triple Entente, or Allies--the British Empire, France, and Russia.

Meanwhile, many in the country's large German American community, which comprised approximately 10% of the overall population, felt a sense of loyalty to their ancestral homeland. Other immigrant groups from various corners of Europe and beyond likewise found their allegiances being pulled in one direction or another. Irish Americans' overall antipathy toward the Allied cause, arising from anti-British sentiments, is but one other example of this dissension.

No doubt aware of the contentious, anxious mood of the country at that crucial moment, and certainly knowing that the nation was unprepared to go to war, Wilson responded to the Lusitania crisis with hesitance, carefully threading the needle between diplomacy and belligerence. His initial response, announcing that there was "such a thing as a nation being so right it does not need to convince others by force that it is right," may have reassured pacifists, but its overtones of American exceptionalism rubbed others the wrong way. Indeed, to many Americans, Wilson's high-minded stance betokened spinelessness. Perhaps realizing his misstep, the president changed course, issuing a series of sharply worded protest notes to the German government, which stipulated ultimately that Germany must apologize for the sinking and compensate American victims. Further similar incidents would, he added, be viewed as "deliberately unfriendly"--language that intimated the threat of a military retaliation.

Faced with possible American intervention in the fighting, Germany finally acceded to Wilson's demands, agreeing to the cessation of unrestricted submarine warfare. For the moment the country remained at peace. But not everyone was happy with the president's handling of the affair. Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan, an avowed pacifist, resigned his position in protest, feeling that Wilson's response evinced a pro-British bias that was edging the country closer to war on the side of the Allies. At the other end of the spectrum, the hawkish Theodore Roosevelt publicly accused Wilson of cowardice in the face of German aggression.

In the apprehensive months following the loss of the Lusitania, the preparedness movement in the United States gathered steam as increasing numbers of Americans began to lobby in support of military readiness, if not for outright intervention in the conflict. Gradually, in this rising martial climate, the voices of peace began losing sway.

Enter Winsor McCay

One American who felt a sense of outrage toward the Lusitania tragedy was cartoonist and animator Winsor McCay. By 1915, the forty-seven-year-old McCay was well known as the creator of the Little Nemo comic strip as well as for having produced several innovative animated films, including How a Mosquito Operates and Gertie the Dinosaur. Even before the Lusitania incident, he had decried the poor state of the nation's army and navy through his work as an editorial cartoonist for William Randolph Hearst's New York American. Now, dismayed by what he perceived as Wilson's tepid response to Germany's affront, he set out do something further: to produce an animated film that would not only accurately record the sinking but also arouse the nation's patriotism by highlighting the depths of Germany's treachery.

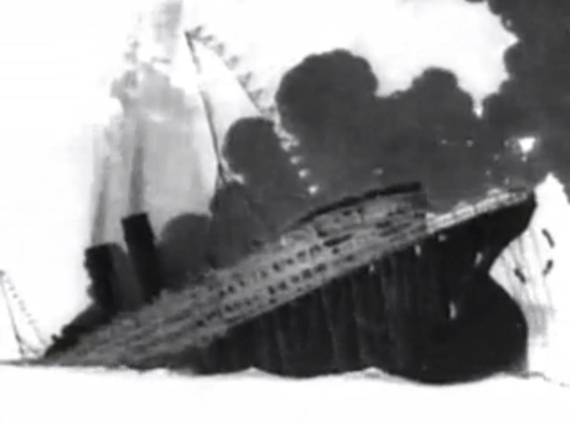

As had been the case with his previous animation projects, McCay self-financed the film, working on it in his spare time with the aid of a small team of assistants. From the outset, their progress was slow. McCay had decided to utilize a newly invented animation technique, the cel process, that allowed animators to produce layers of dynamic drawings over a static background, obviating the need to retrace these still images again and again--in theory, a time-saving measure. However, his inexperience with the new process necessitated an experimental, learn-as-you-go approach, resulting in mistakes and delays. McCay himself claimed that it took eight weeks to produce just eight second's worth of film, though this was almost certainly an exaggeration--at that rate, the twelve minute movie would have taken nearly fifteen years to complete.

While McCay proceeded bit by bit, events in the United States moved at a faster clip, turning swiftly away from peace. Woodrow Wilson was reelected in November 1916 on the strength of his neutrality platform, summed up by his campaign slogan, "He kept us out of war." But by early 1917, with Germany's resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare, this neutral stance was becoming more difficult to maintain. The situation came to a head on March 1 when an intercepted telegram sent by German Foreign Secretary Arthur Zimmermann was revealed to the American press. The message secretly proposed a German-Mexican military alliance: if Mexico would join the war against the United States, Germany would help Mexico reclaim lost territories in Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas. The so-called Zimmermann Telegram, with its threat to American sovereignty, further angered the country. Having exhausted diplomacy, on April 2, 1917, Wilson asked congress to declare war against Imperial Germany. "The world," he said, "must be made safe for democracy." Congress honored Wilson's request four days later with an overwhelmingly supportive vote.

The Sinking of the Lusitania

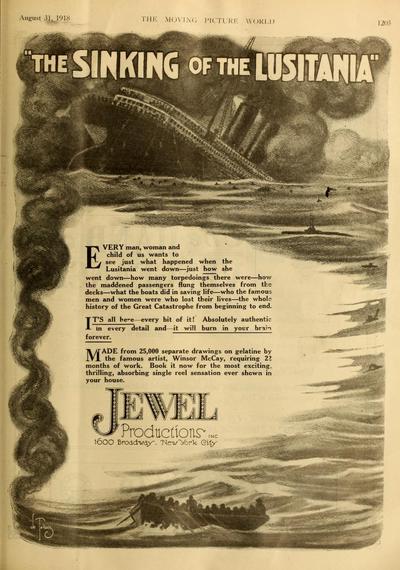

McCay completed his film, now titled The Sinking of the Lusitania, three weeks after the war declaration. It premiered in a private showing at the National Press Club in Washington, D.C., on May 2. Reviewing the feature the following day, The Washington Post remarked that McCay had produced "a powerful picture" that "makes a man want to go out and enlist." As a proud patriot whose son and son-in-law were both serving in the army, McCay was surely pleased with this response. Another showing of the film took place at the Strand Theatre in Manhattan during the week of April 28, 1918, as part of a Liberty bond rally. In its May 18, 1918 issue, the trade publication The Moving Picture World lauded the movie's realism, along with its ability to instill further hatred for the tragedy's German perpetrators. It also noted the emotional impact of the accompanying musical selections: as the Lusitania slipped beneath the waves on screen, the theatre orchestra played the emotive hymn "Nearer, My God, to Thee."

Bolstered by these successful early showings, McCay signed a distribution deal with Jewel Productions, whereby the film would receive a wider release. On July 20, 1918, The Sinking of the Lusitania debuted across the country, billed as the "world's only record of the crime that shocked humanity." But this assertion was not entirely accurate. By then, several other Lusitania¬-themed productions had already made their way into America's movie palaces. One of these, a melodrama titled Lest We Forget, even starred an actual survivor of the attack, the popular actress Rita Jolivet.

Still, McCay's film stood apart from its competitors in its attempt to provide an historically correct depiction of the sinking, and it was very likely this realism that proved most striking to contemporary audiences. Here, it bears remembering that no actual photographs or movies of the Lusitania disaster existed. In our present super-connected world, cell phone video of such an event would be available almost instantly, with survivors tweeting their experiences directly from the life boats. But one hundred years ago, technology of this sort was nearly beyond imagining. Instead, lacking any direct visual documentation, Americans formed their impressions of the incident through written accounts or by way of the many illustrations that were created for newspapers, magazines, and propaganda posters. McCay's movie helped to alter this situation. With its authentic-looking, newsreel aesthetic, the picture no doubt supplied many people with their first--and, perhaps, most lasting--visualization of the disaster, providing a shared visual framework onto which movie audiences could project their own understandings of the event.

By all accounts, The Sinking of the Lusitania was well received both by the public and critics, yet it failed to net its creator a profit. (According to McCay's biographer, John Canemaker, after several years of exhibition, the film only managed to earn $80,000, which barely offset the overall investment.) This financial shortfall may have been attributable in part to the large number of war-related movies that were by then saturating the market, including the already-mentioned Lusitania features.

In the wake America's war declaration, studio executives rushed to demonstrate their loyalty by producing a raft of virulently anti-German films that not only appealed to movie-goer's patriotic sentiments but also sought to demonize the Kaiser and his country. Movies such as The Prussian Cur; The Kaiser, Beast of Berlin; My Four Years in Germany; and The Heart of Humanity played to packed audiences, tapping into the xenophobic, nationalistic, and often hysterical zeitgeist of the period. Though McCay's Lusitania movie was unique in its mixture of animation and propaganda, it may have suffered from being perceived as merely one more of these "Hate-the-Hun" pictures. Then, as now, the attention span of the public was short, and the box office choices were many. How many Germany-bashing, hyper-patriotic films could a busy and, perhaps, somewhat war-weary individual be expected to see each month, anyway?

Legacy

Sadly, after 1918 McCay produced only a few more movies before being forced by his employer, Hearst, to give up his outside animation projects. At the time of his death in 1934, his work had lapsed into a period of semi-obscurity, being eclipsed by the new, innovative productions of animators such as Walt Disney. Happily, though, more recent times have witnessed a revival of his reputation, and he is now accorded the artistic due that he so richly deserves.

One hundred years after the event that inspired it, The Sinking of the Lusitania is viewed by many as a landmark in the development of animation. The film's documentary style, with its implied camera angles and attention to detail, raised the bar for serious animation of the period, much of which had barely progressed beyond rudimentary line drawings. Moreover, in treating a serious topical subject, McCay broadened the field's thematic territory: no longer did animators need to confine themselves to simple, amusing stories. Finally, the picture still serves as a textbook study on the use of animation for war-related propaganda. Does it whip up patriotic emotions? It does, indeed. Instill fear in the minds of viewers? Certainly. Demonize with enemy? Without a doubt. There is nothing subtle about the movie. And yet, in its haunting, surreal beauty there is an understated sophistication that is hard to ignore. As a promotional advertisement of the time stated, The Sinking of the Lusitania is a film that "will burn in your brain forever."

A bit of marketing hyperbole, to be sure, but perhaps not too far off the mark, either.

For further information about Winsor McCay, John Canemaker's Winsor McCay: His Life and Art (New York: Abrams, 2005), from which this piece's biographical details are drawn, is an excellent resource.