We recently disagreed with Andrew Biggs and Sylvester Schieber when they said the retirement crisis is not real. They responded with data showing that people over the age of 65 maintain their standard of living not through adequate retirement savings, but work.

Here's the rub -- work is not retirement. To the contrary, when people have to work in old age due to inadequate retirement savings, that's a retirement crisis.

The Urban Institute and Social Security Administration (SSA) predict that poverty rates among the middle class elderly will be slightly lower than their parents and grandparents. Biggs and Schieber are right about that -- but only if older Americans double their work effort.

Working in old age is not only a violation of this country's historical social contract with workers -- that after a lifetime of work, older Americans should have the choice to leave an increasingly unfriendly workplace without fear of poverty. It is also ineffective. At The Schwartz Center for Economic Policy Analysis (SCEPA), our research has revealed the reality behind the "work longer" solution to the retirement crisis. The shocking fact is that older workers between ages 62 and 65 have seen their job quality eroded by increasingly more physically and mentally demanding jobs. This is also consistent with a gradual decline in older workers' bargaining power, as evidenced by falling pay for older workers and increasing long-term unemployment rates.

Instead, we propose and support efficient and practical pension systems that allow people to save enough during their working lives to retire when they need to, including both when they choose to no longer work or when they are no longer able to work. These solutions include preserving and expanding Social Security benefits by gradually increasing the Social Security payroll tax gradually (which has been stagnant for almost 30 years), securing existing defined benefit plans, and creating universal guaranteed retirement accounts that provide individual, mandatory savings accounts on top of Social Security.

To help highlight the issues and get us to the right policies on retirement reform, we continue the respectful conversation with Biggs and Schieber on the current retirement landscape.

Measuring a Retirees' Ability to Maintain Their Standard of Living

Biggs and Schieber cite one part of a 400+ page OECD report saying the average American over the age of 65 has an income 92 percent of the national average. Unfortunately, this number isn't relevant to the question of a retirement crisis. To understand if people will have enough income to maintain their standard of living in retirement, we need to know how retirees are doing relative to workers.

How we answer this question depends on the metrics. First, income captures both income from retirement savings and earnings from work. Monique Morrissey at the Economic Policy Institute reminds us that American seniors work or look for work at much higher rates than their global counterparts.

Second, because the United States is home to some of the world's most extreme inequalities in income and wealth, the average measure of senior income in the U.S. is skewed upward, distorting the real experience of most seniors.

In this case, median income provides a better reflection of how people are doing. [1] Using the American Community Survey [2], the ratio of median retiree income for those over 65 ($19,400) to the median income of workers aged 25 to 64 ($28,100) [3] is 69 percent, not 92 percent.

But even this measure isn't enough. Rather than just compare the ratio of median income of an older group to a younger group, we must limit the younger group to those with positive earnings, prime-aged individuals engaged in the economy, and limit the older group to those who are retired. With a median income for workers age 25 to 64 at $36,000 and the median income of a retiree [4] at $16,400, the retiree-to-worker median income ratio is 54%. This number is far from Biggs and Schieber's reference in their Wall Street Journal op-ed.

Retirement Insecurity and Income Inequality are Growing

Our research, supported by findings from the National Institute on Retirement Security and the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College, documents that 55 percent of near retirees will have to rely on Social Security as their single source of income in retirement. Biggs and Schieber counter with data from the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) stating that 55 percent of current retiree households receiving Social Security benefits are also receiving income from pensions or savings.

Right, we agree. The private system is failing. Social Security, as designed, is doing its part in maintaining its share of retirement income. The role of pensions is falling. Between 1999 and 2011, employer sponsorship of retirement plans for prime-aged (25 to 64) workers declined from 61 percent to 53 percent. If this trend continues, lack of access to retirement savings vehicles at work will leave more of today's near retirees facing greater insecurity in retirement.

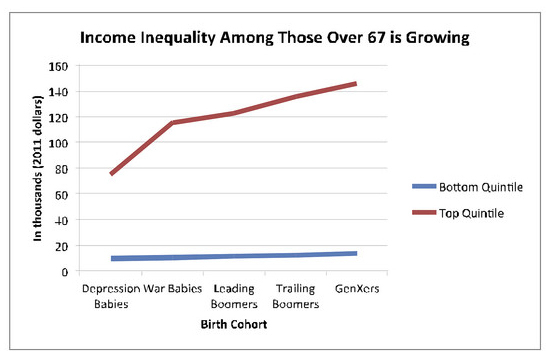

Biggs and Schieber disagree with the very authors of the SSA report they continue to cite. Using the MINT model, Biggs and Schieber praise, the report projects a "dramatic" increase in inequality in earnings and family income at age 67. The SSA documents that median income in the top quintile for those born during the Depression will be 7.5 times higher than those in the bottom income quintile. Among GenXers, the income gap will increase to a factor of more than 10 (see graph below).

We agree with the SSA findings. Future retirees will not be able to replace as much of their pre-retirement earnings as the generations before them. Professor Alicia Munnell from Boston College notes that, in the recent past, Biggs has inflated the Social Security replacement rate -- making the program look more generous -- by including people who have no earnings in the last five years. Munnell writes, "It makes no sense to include zero years in the denominator of the replacement calculation."

Making Seniors Work is Not the Right Path to Economic Growth

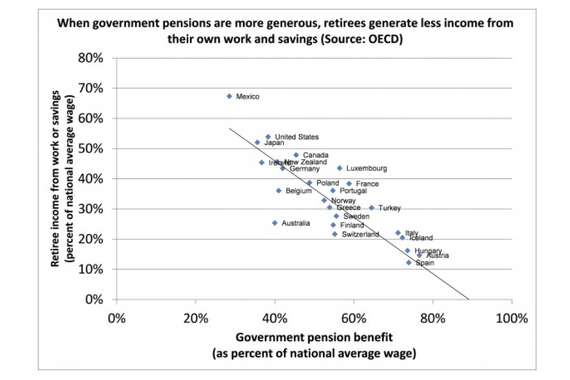

Biggs and Schieber argue that having older people in the workforce promotes economic growth. They are proud that the United States shares the spotlight with Mexico as one of the countries with the smallest pensions and highest levels of older people in the workforce (see the graph below, reproduced from Biggs and Schieber's response to me and also from the OECD report).

Source: As cited by Biggs and Schieber in their response to Teresa Ghilarducci on the American Enterprise Institute website.

Source: As cited by Biggs and Schieber in their response to Teresa Ghilarducci on the American Enterprise Institute website.

At SCEPA, we don't believe Mexico should be our model for how to provide a just and dignified retirement. And while forcing our elderly to work could provide some boost to long-term economic growth, growth is not a reason to make poor policy decisions.

The Joint Economic Committee says we need to get younger people, those 24 to 64-years-old, who want to work a job. Biggs' own institute, AEI, shows that if we push people in their sixties to work, they will have a hard time finding and keeping work. Jobs for older workers are relatively scarce, and age discrimination is rampant.

Living longer doesn't mean people can work longer. Longer lives aren't necessarily healthier or more productive lives. In 2008, men and women could expect to live only 65 and 68 years of their lives free from activity limitations. After age 68, chronic conditions begin to limit the body and mind. Our employment policies should prioritize getting the prime-aged population working, not insisting the elderly have no other choice.

Rather than using fear of deprivation to motivate more 70-year-olds to work at Wal-Mart, let's use pensions to spur economic growth. Pensions and Social Security provide money to households in bad times, thereby stabilizing the economy, and create savings pools. There is a benefit from pensions to anyone convinced of a connection between pools of savings and investments.

Perhaps our disagreement with Biggs and Schieber about the solution to the retirement crisis (efficient retirement institutions that help people save vs. working into old age) has to do with our disagreement about the aims of policy. Biggs and Schieber, like many, view work as a good way for people to supplement their income in old age. We do too. Where we differ is in our belief that pensions and Social Security should provide adequate income to those who want to control the pace and content of their retirement time, to those who cannot find work, and to those with limitations who can no longer work.

End Notes

[1] According to the 2014 OECD Employment Outlook, we also top the list of OECD nations with the highest incidence of low paying jobs, which refers to the share of workers earning less than two-thirds of median earnings.

[2] Mr. Biggs and Mr. Scheiber take issue with our use of ACS and CPS. They argue that these surveys comes short of retirement income reported on federal income tax filings. Monique Morrissey at the Economic Policy Institute has already responded to this.

[3] The median incomes of all those in the 65+ age group come pretty close to 92% of the median incomes of those 15-64 (median total income $19,400 for older people, compared with $20,000 for younger people) which confirms the OECD rough comparisons. But it makes little sense to discard prime-aged workers.

[4] 80.9% of those 65+ do not work, while 19.1% have positive earnings