"Between me and the other world there is ever an unasked question: unasked by some through feelings of delicacy; by others through the difficulty of rightly framing it. All, nevertheless, flutter round it. They approach me in a half- hesitant sort of way, eye me curiously or compassionately, and then, instead of saying directly, How does it feel to be a problem?"

-W.E.B. D Bois The Souls of Black Folk

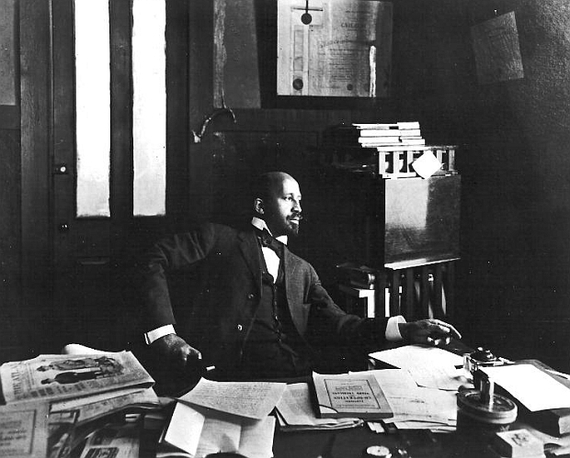

"How does it feel to be a problem?" William Edward Burghardt Du Bois asked this probing question more than a century ago in the first chapter of his seminal work, The Souls of Black Folk. Naturally, the problem of which Du Bois spoke, the problem of Du Bois' day, revolved around the experience of "the Negro" existing as a "seventh son" of sorts, positioned at the bottom of the totem pole of racial stratification--seated beneath "the Egyptian and Indian, the Greek and Roman, the Teuton and Mongolian." As Du Bois mused in his acclaimed work, this seventh son "born with a veil, and gifted with second-sight in this American world," uniquely grasped "a true self-consciousness," one that required "measuring one's soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity." Whether one simply said, "I know an excellent colored man in my town;" or "I fought at Mechanicsville;" or asked, "Do not these Southern outrages make your blood boil?" Du Bois keenly understood those residents of "the other world" all sought a way to frame their underlying question, "How does it feel to be a problem?"

As Du Bois prophetically opined in 1903, America still grapples with the problem of "the relation of the darker to the lighter races" 240 years since it "launched its improbable experiment in democracy," because "[t]he problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color-line ..." Three years before Du Bois' inquiry, James Weldon Johnson captured the angst of African Americans navigating the quagmire of America's racial caste system like this, "Stony the road we trod/Bitter the chastening rod/Felt in the days when hope unborn had died ..." This sad lament has reverberated throughout the generations. "How does it feel to be a problem?" the question deserves asking 113 years after Du Bois first posed it, so I ask it today.

Two years ago, former Ferguson police officer Darren Wilson fatally shot Michael Brown, an unarmed African American teen two days from beginning college, after a brief tussle between the two on Canfield Drive. Following their skirmish, Brown's hefty body laid in the street for nearly four and a half hours; blood trickled from his lifeless frame and began soaking the asphalt of the main thoroughfare passing the Canfield Green apartments located on the westside of Ferguson, MO. Onlookers soon gathered to explore the nature of the incident. Their curiosity quickly boiled into frustration, and those frustrations bubbled over into more than 100 consecutive days of protests. Those who sought to "petition the government for a redress of grievances" voiced concerns not only with the death of Michael Brown, but also at a larger system of injustice that deemed them disposable. In his newly published book "Nobody: Casualties of America's War on the Vulnerable, from Ferguson to Flint and Beyond," Marc Lamont Hill described it as such:

There was not only Brown's shooting to consider; there was also the aftermath. There was Brown's body, left for hours on the hot pavement, his crimson blood puddling next to his young head, staining the street, flowing in a crisscross pattern, a tributary running slowly to the gutter. Eventually, an officer produced a bedsheet and placed it over Brown's frame, a figure so large that the cover could not shield it all, the oversized teenager's legs left peeking out from the bottom. Though it was early August, a wintry stillness set in over the next four hours, as police officers stood stone-faced and crowds of passers-by gazed in astonishment. While this was happening, Michael Brown remained on the street, discarded like animal entrails behind a butcher shop. As Keisha, a local resident who I interviewed a week after the shooting, said to me, "They just left him there . . . Like he ain't belong to nobody."

As an African American reared below the Mason Dixon, I find significant portions of my personal narrative's arc bending along the color line Du Bois referenced. My mother was born in Memphis, TN during a time where local officials routinely delayed the removal of "White Only" signs from public accommodations, even after federal mandates to do so. My father immigrated to the United States from Ghana in the early 1970s, and upon his arrival, experienced racism and xenophobia at a level in which he still finds difficult to speak of to this day. I spent the bulk of my formative years dutifully attending gatherings in traditional black churches in Tennessee and Georgia respectively. Like scores of my forebears, I found a place to tabernacle with God in those cramped edifices with stained glass windows and creaky floors. The stories of my parents, the stories of my ancestors resonate with me. In many ways, it served as the inspiration behind my latest work--a song entitled The Souls of Black Folk.

The song, and its corresponding video, draws much of its influence from W.E.B. Du Bois' work of the same name. The song is part jazz, part gospel, part spoken word, yet all hip-hop. In many ways, it functions as a contemporary version of Lift Ev'ry Voice. Consequently, its content wrestles with the collective plight of African Americans seeking to overcome the nation's tortuous endeavor to "the [relate] ... the darker to the lighter races."

In the song's corresponding video, I play a pastor of a church whose building is bombed by people angered by the pastor's community activism. In so doing, the video captures the harrowing reality African Americans have endured for centuries, particularly as it relates to the terror imposed by reoccurring attacks on traditional black churches. The video debuted on the second anniversary of Michael Brown's death as a means to further communicate how the struggle to rise above the color line persists. For centuries, the color line has robbed people of their humanity. Here is my contribution to help us rise above it.