When Pope Francis, in his historic speech to Congress, spotlighted Dorothy Day and Thomas Merton, I let out a shout -- and no wonder. Just minutes before, I had finished the pitch to a literary agent for my book project -- 10 years in the making -- called Bearing Witness: Dorothy Day, Thomas Merton, and the Question of Belief in Times of Crisis. And as I wrote in that pitch, "Day and Merton's social justice witness, deep spirituality, and loathing of sanctimony -- all in service of the call to love -- are the very traits that make Francis such a compelling figure in our own time of crisis."

Dorothy Day (1897-1980) co-founded the Catholic Worker in 1933 and led this network of communities devoted to prayer, solidarity with the poor, and peace. She was unanimously recommended by the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops for sainthood in 2012, which surprised some observers, given her radical antiwar stances, and with some Catholic Workers fearing that this side of her legacy would get downplayed by the Vatican. But now the Pope has lauded, to Congress and the nation, "Her social activism, her passion for justice and for the cause of the oppressed [which] were inspired by the Gospel, her faith, and the example of the saints." Today the Catholic Worker consists of more than 200 Houses of Hospitality in the U.S. and about 30 others spread across Europe, Africa, Australia and Latin America.

The Catholic Worker published landmark antiwar essays in the early 1960s by Thomas Merton (1915-1968), who was made famous in 1948 by his bestselling autobiography, The Seven Storey Mountain: the story of an urbane intellectual who became a cloistered monk. In the scores of books that followed, all still in print, he pioneered what he called "contemplation in a world of action," anticipating the popularity of meditation in our own time. The Dalai Lama has written that he first learned the essence of the true Christian spirit from Thomas Merton.

For some in the Church hierarchy his openness to Buddhism was a cause for concern, but the Pope, who (like the Dalai Lama) meditates over an hour each day, lauded the monk as "a man of prayer, a thinker who challenged the certitudes of his time and opened new horizons for souls and for the Church. He was also a man of dialogue, a promoter of peace between peoples and religions."

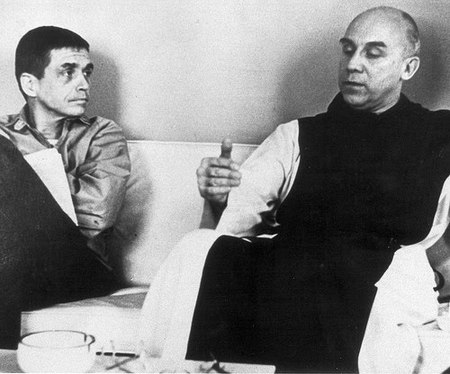

Thomas Merton (right), talking to Daniel Berrigan at the peace retreat Merton organized at his monastery, 1964 -- [photo by Jim Forest]

Thomas Merton (right), talking to Daniel Berrigan at the peace retreat Merton organized at his monastery, 1964 -- [photo by Jim Forest]

Bearing Witness is the first book to plumb Day and Merton's personal journals in tandem, and they underscore the fact that these two visionaries shared a searching, almost existential sensibility that resonates in our own anxious times. Like Francis, who always says, "Pray for me," they knew in their bones that sanctimony is the occupational hazard of religious people, and they were keenly aware of their own flaws (as I noted on a New York Public Radio segment on the Pope's speech.)

Jim Forest, who was close to both of them and wrote moving biographies of each of them (and who has been encouraging of my own project), once characterized Dorothy Day as the patron saint of people who can be impatient, and in one of his interviews with me he mused that Merton might well have become alcoholic if he had not entered the monastic life. She went to confession weekly, while his most famous prayer begins, "My Lord God, I have no idea where I am going..."

Their compelling correspondence triggered my own Day/Merton epiphany a decade ago. Preoccupied with worries large and small, I was also troubled by my suburban comforts in comparison to a Catholic Worker friend who lived in voluntary poverty. He had introduced me to Dorothy Day and Thomas Merton's writings in the late 1960s, and now I found myself turning over in my mind which of the two was more inspiring.

Was it Dorothy Day, trying so heroically to live out the Gospel message: love God, your neighbor? Or was it Thomas Merton, who recovered the 1500-year-old heritage of Christian meditation? But, then, Day herself was dedicated to meditation, while Merton, for his part, had taken a vow of poverty. And while she was the person out in the world -- living in New York City when not speaking around the country -- and he was the one in the monastery deep in the Kentucky woods, in fact it was Day, with her self-disciplined prayer life, who was sometimes nicknamed "the abbess," while Merton was a charmer who corresponded with everybody from Boris Pasternak to Henry Miller.

Suddenly it hit me: what mattered was Day and Merton together. Did they know this? Sure enough, the collection of Merton's letters on my bookshelf revealed the compelling nature of their exchanges, as when he wrote to Dorothy Day to praise her response to the latest statement by Cardinal Spellman of New York promoting U.S. escalation of the Vietnam War.

I have read your latest piece in the CW on Cardinal Spellman and the war. It is beautifully done, soft-toned and restrained, and speaks of love more than reproof. It is the way a Christian should speak up, and we can all be grateful to you for speaking this way. It has to be done. The moral insensitivity of those in authority...has to be pointed out and if possible dispelled. It does not imply that we ourselves are perfect or infallible. But what is a Church after all except a community in which truth is shared.

Yes, Lent is a joy... A little emptiness does one good...

At the same time, as a historian I take the evidence wherever it leads: addressing their personal limitations, certainly, and also the ways in which, as Catholics -- ones of their time and place -- they held some positions related to sex/gender that are abhorrent to many people today. Even if neither one emphasized these issues, neither one challenged their Church on them, either, and in this respect they mirror Francis in ways that many understandably find less than appealing.

But it is also the case that Dorothy Day said, "The Church is the cross on which Christ is crucified." She was quoting theologian Romano Guardini, who was also cited by Merton. And Guardini happens to be the Pope's favorite theologian (e.g. the one most referenced in his environmental encyclical). This, even as Day, Merton, and Francis all remind us that none of us are God.

The Day/Merton relationship even reveals a crucial element of the Pope's message that most of the media miss. They note his call for compassion regarding those on the margins, and sometimes they mention his call for championing the rights of the weak, but few journalists make clear his central emphasis on "the least" as the most important people of all. Not that they are more virtuous or wise than other people, but that the poor and wounded in our midst are especially beloved of God, and thus especially deserving of our respect and favor, even as we are called to love all people as children of God.

It is in promoting this value that Francis is in deepest communion with Thomas Merton and Dorothy Day. Now that we have a Pope who strives to bear witness to that love in action, let us hope that he progresses along that path -- and that we do, too.