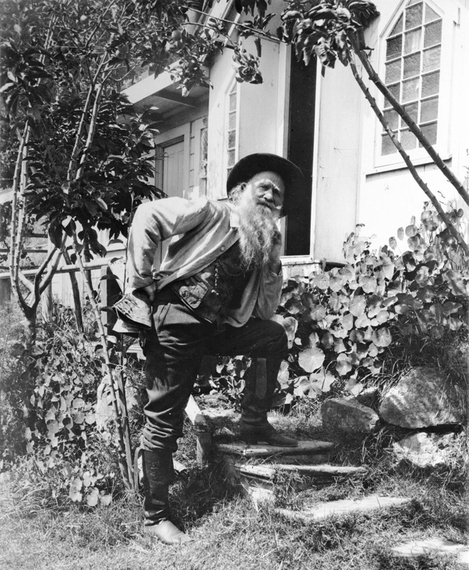

"A thousand leaves on every tree, and each a miracle to me" -- Joaquin Miller

Take a hike in the forests of the Oakland hills, and sooner or later, you are likely to bump into a trail marker containing the image of Joaquin Miller, an early settler to the city responsible, in part, for the lush forests which blanket the hills. A colorful figure from the 19th century, famed in his day for his poems celebrating the West's spectacular natural beauty, Miller was called the "Poet of the Sierras" and today has the distinction of having an Oakland street, Oakland elementary school and Oakland park named in his honor. The founder of California's first Arbor Day, Miller planted the land that is now a park bearing his name with 75,000 trees, mostly Eucalyptus, Monterey Pine and Monterey Cypress, three of the very species of trees now slated for eradication across 2,059 acres of public lands in Oakland, Berkeley and surrounding cities.

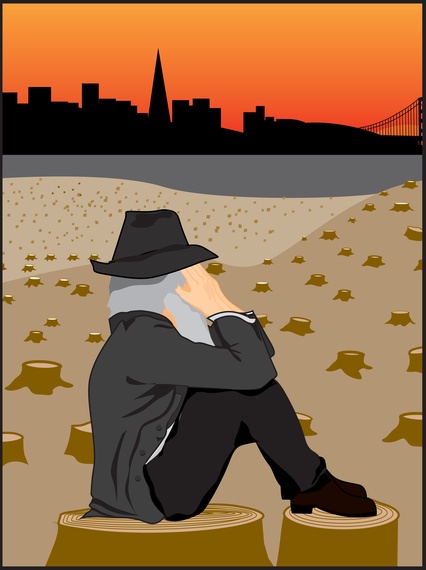

After timber hungry fortune seekers arrived in droves to the San Francisco Bay Area during the Gold Rush and clear cut the Oak trees which gave the city of Oakland its name, early settlers like Miller looked about the blighted hillsides so prone to devastating fires which regularly swept across the empty grasslands and undertook a deliberate campaign of beautification and forestation--a plan that has bequeathed to us what is now one of the most spectacular natural jewels of the Bay Area: the forests of the East Bay hills. When encroaching development subsequently threatened these forests in the early part of the 20th century, Bay Area naturalists, including Robert Sibley, set about preserving them, creating the East Bay Regional Parks District and with it, many of the now most beloved and heavily visited public parks in the East Bay.

Today, these publicly owned lands contain forests that are an integral part of the San Francisco Bay Area's historical heritage, a living link to our past that remain as beautiful and cherished by most East Bay residents as on the day these parks were founded. And while every generation since their planting has been blessed by public officials who embody and reflect the public's love and appreciation for these trees, ours has not been so fortunate. The City of Oakland, the East Bay Regional Park District and the University of California at Berkeley are now staffed by people seeking to destroy the very trees their predecessors sought to protect.

Championing a plan to cut down over 400,000 trees and spread toxic herbicides upon their stumps, they will (in their own words) "eradicate" these forests forever so that the land upon which they grow can be converted back to that which Miller and other early residents sought to beautify: "grassland with islands of shrub." Where once the EBRPD called our Eucalyptus forests "keynote features" which should be protected for future generations, stating that "special efforts should be made to promote and protect wildlife in all its forms by not disturbing the natural cover," today's EBRPD administrators unabashedly claim their goal is to chop these trees down.

Armed with federal and local taxpayer funds to pay for their deforestation agenda, they are moving forward with a plan that will, over the course of the coming decade, methodically destroy -- bit by bit -- these living embodiments of the region's history. With chainsaws and herbicides, they will undo that which over a century ago Oakland citizens bestowed to future generations by shovel, seedling and great personal effort: hundreds of thousands of towering, majestic, carbon sequestering, shade giving, animal habitat creating, fire preventing, soul nourishing trees.

The question, of course, is why? More specifically, why an area noted for embracing environmentalism is intent on deforestation and poisoning San Francisco's East Bay public land, including wildlife corridors, recreation areas, and residential neighborhoods? If you believe proponents, it is because the trees pose a risk of fire. They have worked tirelessly to turn public opinion in the East Bay against Eucalyptus trees since the infamous Firestorm of 1991 which burned scores of homes and killed 25 people. Chief among their claims is that these trees were to blame for the ferocity of that fire because they are alleged to possess unusually high quantities of volatile oils that make them more flammable and prone to shooting off embers which enable the spread of fire. These claims have been repeated so many times they are often regarded as self-evident, even though the evidence does not support them, nor does the history relating to the ignition and spread of past fires in the hills. Indeed, the 1991 fire and a later 2008 fire in the region started not in trees, but in grasses, the very sort of vegetation that clearcutting will, by deliberate design, proliferate throughout the hills. In fact, the stated aim of the deforestation effort is to replace the East Bay's Eucalyptus and Monterey Pine forests -- forests containing species of trees that are among some of the tallest in the world -- with shallow grasses, grasses that are highly susceptible to fire and which even the EBRPD has admitted on their website are "one of the most dangerous vegetation types for firefighter safety due to the rapid frontal spread of fire that can catch suppression personnel off guard."

In a report highlighting the heightened fire risk which will result from this plan, David Maloney, a former Oakland Firefighter and Chief of Fire Prevention at the Oakland Army Base, criticizes the spread of misinformation about Eucalyptus as motivated not by a genuine fire abatement goal, but native plant ideology. Maloney writes that the plan is "a land transformation plan disguised as a wildfire hazard mitigation plan" that will "endanger firefighters and the general public... and be an outrageous waste of taxpayer money." He notes that claims about the peculiar flammability of Eucalyptus are unfounded, calling them, "propagandistic statements which are designed to scare the public, which have no basis in fire science... Fire Science has proven that every living tree -- regardless of its species -- due to its moisture content and canopy coverage of ground fuels, contributes to wildfire hazard mitigation." For example, morning and evening fog drip in Eucalyptus forests has been measured at over 16 inches per year in the Bay Area, even during hot, dry summers. Given the recent drought, this fog drip provides one of the few sources of moisture our public lands have been receiving.

Photo: The Scripps Ranch Fire of 2003 burned 150 homes but none of the Eucalyptus abutting those homes.

Moreover, Bay Laurels, a preferred species by "native" plant advocates, possess higher oil content than Eucalyptus, Acacia, Monterey Pine, and Monterey Cypress and yet these trees will not be removed, highlighting, again, an alternative motivation than fire abatement. According to Cornell University, essential/volatile oils in Blue Gum Eucalyptus leaves range from less than 1.5 to over 3.5%. While the leaves of California Bay Laurel trees contain 7.5% of essential/volatile oils, more than twice the amount of oil in leaves of Blue Gums.

Not only are Eucalyptus trees very fire resistant, but they provide a variety of other benefits as well. Eucalyptus trees, for example, increase biodiversity, with a 1990 survey in Tilden Park, one of the parks slated for deforestation, finding 38 different species beneath the main canopy of Eucalyptus forests, compared to only 18 under Oak trees. Indeed, Eucalyptus provide nesting sites for hawks, owls and over 100 other species of birds. They are also are one of the few sources of nectar for Northern California bees in the winter and are crucial for migrating Monarch butterflies. Eucalyptus trees benefit other trees, as well. Without the Eucalyptus trees to capture and distill the moisture in fog, Oaks currently growing under the canopy of Eucalyptus would be unable to survive in many of the areas in the hills they can now be found, areas which would otherwise be too dry to sustain them. Lastly, they benefit the human residents of the hills by not only providing breathtaking natural beauty, shady hiking trails and serene, peaceful escapes from the hectic pace of day to day life, they trap particulate pollution, sequester carbon and prevent soil erosion in the hills -- a particular concern to hills residents whose homes are located above steep hillsides of Eucalyptus forest now slated for eradication.

Given that Eucalyptus trees are so beautiful and environmentally beneficial, what is the real reason proponents of deforestation want to clearcut them? They claim that the trees are "non-native," a pejorative term based on an idea we have thoroughly rejected in our treatment of our fellow human beings -- that the value of a living being can be reduced merely to its place of long ago evolutionary origin. But even accepting the discriminatory and unscientific underlying premise which responsible environmentalists are beginning to reject in ever increasing numbers -- that the word can and should be divided between "native" plants and animals who are worthy of protecting and "non-native" plants and animals who deserve to die -- the claim that that Eucalyptus trees are "non-native" is being challenged as well. Given that Eucalyptus readily hybridize with other species and have created types of Eucalyptus trees which originated in California and can be found nowhere else, some claim "we might now have some California eucalyptus hybrids that could rightly be considered native, or at least have earned full citizenship."

For those of us who were born and raised in California, have lived here most of our lives and have found ourselves surrounded by Eucalyptus trees and forests wherever we may travel in this beautiful state, the suggestion that trees which are so abundant and have been here for over a century should be considered anything but iconically Californian betrays both logic and experience and the deep affection so many of us feel for them.

In 1933, Gertrude Stein is credited with describing Oakland with the famous quip, "There no there there." It has been used by Oakland-bashers ever since. In truth, Oakland has a lot going for it. And in the Oakland hills, it's got the forests; forests filled with hundreds of thousands of majestic, towering, beautiful, quintessentially "Oaklandish" Eucalyptus trees. Indeed, when asked what he would miss most after being traded from the A's to the Yankees, Mr. October himself, hall-of-fame slugger Reggie Jackson, said, quite simply, "I'll miss the trees." So will we all. Because if this plan is allowed to proceed -- at least as it relates to the Oakland hills -- Stein's words may yet prove prophetic.

Both Nathan & Jennifer Winograd contributed to this article.