To assert that economists are having trouble figuring out the relationship between inflation and unemployment is like saying chefs can't figure out what to do with salt and pepper. It's that fundamental. Yet, we're befuddled, and that has powerful policy implications.

For example, a prominent macro economist recently suggested to me that we must have been at full employment for the past 20 years, because inflation has essentially hovered around the Fed's target of 2% since then (average core PCE, year-over-year, since 1994: 1.7%; standard deviation: 0.4%). If output gaps truly persisted, then inflation should have fallen well below this band; if we were overheated, vice versa.

Given the obvious absence of full employment in recent years, I think his point was really that traditional relationships between critical variables are shifting in ways we don't understand. And given how large this relationship looms both as a policy determinant at the Fed and in understanding the dynamics behind their mandate to balance full employment and price stability, this is a serious problem.

To be clear, in discussing our lack of understanding of the unemployment/inflation tradeoff, I'm not talking about the rabid inflation hawks who've been tilting at an inflationary phantom for years now, though they're not a trivial group. I recently testified in Congress alongside my old friend Larry Kudlow, who called the fact that inflation has been quiescent "miraculous." As Paul Krugman noted about this interpretation: "It's not something wrong with my model. It's a miracle!" (To give Larry credit, at least he's not veering into the wing-nuttery claim that the statistical agencies are cooking the books.)

I'm thinking about the rest of us, starting at the top--with the Fed--who are struggling to figure out the nature of the tradeoff as the Fed begins to contemplate unwinding. Given Chair Yellen's (very appropriate) focus on job-market slack and thus her up-weighting of the full employment side of the mandate, there's clearly some anxiety building around the potential for overshooting on inflation.

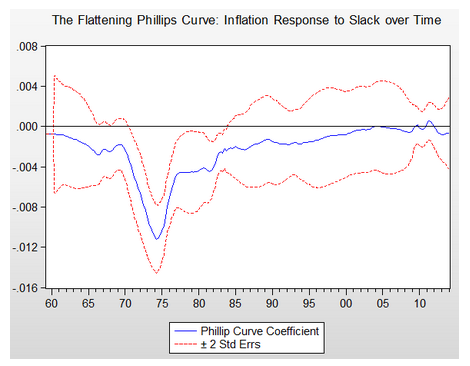

A big part of the problem is the evolution of the inverse relationship between unemployment and price growth, i.e., the flattening of the Phillips curve, implying a reduced negative correlation between inflation and unemployment. This phenomenon is by now fairly well known; the figure below (see here for more explanation) shows how much the correlation has diminished over time.

Source: author's analysis of Ball/Mazumder model.

Why has it flattened so much? The Fed has done a good job of convincing people that it will keep inflation "well-anchored" no matter what else is going on, higher inequality means stickier wages, globalization has reduced supply constraints, and especially in recent years, the unemployment rate is widely regarded as an inadequate measure of slack.

One implication of this, as David Mericle of Goldman Sachs Research recently wrote (no link) is that "...looking ahead, the flattening of the Phillips curve implies that the inflation costs of misjudging slack--however measured--are likely to be smaller than in the past."

Of course, one could argue that another implication is that if inflation did start to climb quickly, "flat Phil" also means that it would be harder to slow inflation through higher unemployment. That's possible, but the above list of "flattening factors" is pointing solidly in the other direction. In fact, I'd say the experience of the 20 years suggests an anti-inflation bias in most advanced economies, with Japan of course leading the pack.

To be clear, I think the unemployment/inflation tradeoff lives on--I don't believe the zero at the end of that Phillips curve figure above. But I'm afraid that's about the extent of what we know right now.

A related problem, noted above, is how to measure slack, the key input into this relationship. Given the decline in the labor force, a phenomenon partly driven by weak demand, the unemployment rate is a less reliable indicator (you're only counted as unemployed if you're actively searching for a job). That's led the Fed to adopt a "dashboard" approach, involving a plethora of indicators, including underemployment, new hires, payroll growth, wage trends, and more.

I think that's both smart and necessary, but it further complicates our understanding of the tradeoff and makes it harder for us to understand what the Fed is up to (remember when they blew by their erstwhile 6.5% unemployment target?). Mericle evaluates the state of the dashboard indicators and finds something quite interesting: the level indicators, like underemployment or the quits rate, are still below their target ranges. But the rate-of-change indicators, like payroll growth, are much closer to the target.

By this analysis, there's still too much slack but it's closing at a decent clip. How does that map onto inflationary pressures? Who knows?!

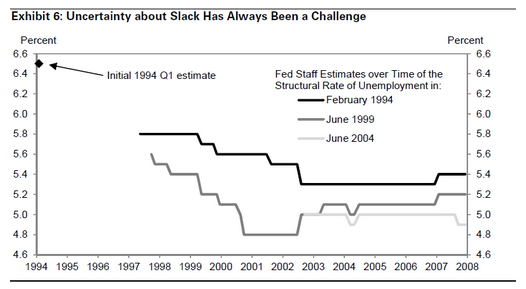

Next, pretend for a moment that the unemployment rate accurately reflects labor market conditions. To assess the extent of slack, you still need an estimate of the lowest unemployment rate consistent with stable prices (the so-called "structural rate"). And that number, which changes over time, is elusive to say the least. While economists still crank out such estimates with abandon (even adding numerous decimal points, just to show we've got a sense of humor), Dean Baker and I recently pointed out that the confidence interval around these guesses is a whopping four percentage points.

Moreover, like I said, it moves. Mericle prints the figure below showing Fed staff estimates of the structural rate over time, from the mid-6's to the high 4's.

Source: David Mericle, GS Research; Philadelphia Fed.

One begins to see how challenging this question of inflation and unemployment has become. The world has changed in ways that both significantly alter this relationship and make it harder to measure. Importantly, those global changes are not random: they lean towards a weaker correlation between slack and price pressures.

So what's the best way forward? First, as the increased analytic scope at the Fed has shown, the simple, two-variable Phillips curve may be a tired, old macroeconomic war horse that should be put out to pasture if not sent to the glue factory. It simply can no longer provide the guidance we need.

Second, as I've stressed throughout, the history of inflation in recent decades suggests that risk of overshooting is diminished, and even if we do, there's nothing wrong with slightly higher inflation (there is, of course, a problem with spiraling price growth, but the factors holding down inflation--anchoring by the Fed, global supply chains, restrained wage growth--lower that risk). Conversely, the risk of persistently slack job markets is seen and felt by millions every day, and not just for the millions still unemployed and underemployed, but in the paychecks of the vast majority of the workforce.

Simply put, we cannot afford to continue to sacrifice the goal of full employment at the altar of an inflation hawkery that is increasingly out of step with both the data and the changes in the historical relationship between unemployment and price pressures. To their great credit, the Yellen Fed seems to get this, but as time progresses and prices firm--as I said, that correlation isn't really zero--they'll be hearing a lot about "overshoot risk." An honest assessment of what we know should lead them to discount that risk as they keep their eyes on the dashboard and their feet gingerly on the gas.

This post originally appeared at Jared Bernstein's On The Economy blog.