"Epitaph" for Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald, Kenneth Britton, The New Yorker, 1926

The first issue of The New Yorker magazine appeared on 21 February 1925. "Not edited for the little old lady in Dubuque," as the always-misquoted phrase actually appears in print, the Manhattan-based magazine sold itself from the start as urban and urbane -- a magazine for the literati and literate. In February 1925, Scott Fitzgerald was in Rome, revising the galleys of The Great Gatsby. From the Hotel des Princes, Fitzgerald announced in a letter to a friend: "I've written a novel, Patsby, that's just about the best one written in America for twenty years. It appears in the spring. I'd tell you the name only I'm going to change it." He may not have told his friend the name of his book, but, either jokingly or unavoidably, Fitzgerald spelled her name not "Patsy" but "Patsby" throughout the letter. On April 10, 1925, Scribner's published The Great Gatsby in New York.

The young author was already famous, thanks to his first novel, This Side of Paradise (1920); the young magazine would quickly become so. The New Yorker appeared at the heart of the decade Fitzgerald named the Jazz Age, and, as a literary, social, and intellectual magazine concerned primarily with New York city and the cosmopolitan metropolitan area from Southampton to Saratoga, The New Yorker chronicled the same events, people, and scenes from which Fitzgerald took much of his inspiration for fiction. This Side of Paradise gets scary and seamy -- and so very exciting -- when the Princeton boys take those trains into the city, and out to the posh spots of Long Island. Gatsby veers along those new commuter rail lines and new roads between Wall Street and the Hamptons, the restaurants and businesses and hotels of Manhattan crucial settings for the novel's events. Even Fitzgerald's Riviera masterpiece, Tender Is The Night, is populated, and haunted, by Americans who hail from New York, who refer to it constantly, and whose names, like McKisco, evoke its suburbs long before the novel's end fades back to the city, and the Empire State beyond, to Geneva, Hornell, to "a very small town -- in that section of the country, in one town or another."

Today we are well accustomed to having some of the most enduring names in American letters long associated with The New Yorker: John Updike, appearing there for nearly sixty years; E. B. White; James Thurber; John Cheever; Rachel Carson; John McPhee; Dorothy Parker; Jay McInerney; Seymour Hersh; and many more. Logically, we look back at The New Yorker during its first days, and expect to see Hemingway, Fitzgerald, and Faulkner publishing in it. The Jazz Age Manhattan magazine, to our retrospective eyes, should surely have carried Fitzgerald as its biggest-name contributor, poster boy, alter ego.

However, The New Yorker was a newcomer in 1925. Fitzgerald had arrived in 1920 -- so young himself, but half a decade earlier. Already-established names in contemporary writing, many of them authors under thirty, published instead in Collier's, The Saturday Evening Post, Smart Set, and, particularly if their books were published by the parent organization, Scribner's Magazine. By the 1930s, more recent arrivals like E. B. White, James Thurber, and John O'Hara, along with The New Yorker's founding folk like George S. Kaufman, Rea Irvin, and Dorothy Parker, would be getting known for their fiction as well as essays, reviews and illustrations. Fitzgerald, though, generally remained too much in demand for The New Yorker, and beyond its budget -- much to its regret -- in the first decade of its life.

This patently bothered people at the magazine. They would have loved to publish Fitzgerald, and did snap up occasional writings whenever they could -- such as his infamous drinker's "Short Autobiography," in the 25 May 1929 number. But for years The New Yorker's connection to Fitzgerald was largely restricted to reviewing his books and collections when they appeared -- generally unfavorably, or at least without much visible affection -- although the magazine was peppered with cartoons, couplets, little asides and mentions of Fitzgerald that have gone uncollected, and largely unnoticed until now. The attention that The New Yorker paid to Fitzgerald and his work was sometimes envious, sometimes admiring, sometimes quite entertaining, and sometimes sadly dismissive, considering both the source and the author.

The real world upon which The New Yorker reported and the fictional world that The Great Gatsby depicted were remarkably similar, which is unsurprising given Fitzgerald's basing his novel on the places, people, and events of the short corridor - less than 25 miles - from Manhattan to Great Neck. The public spectacles were elaborate and varied. Women's golf, Jordan Baker's event, received extensive coverage. Baseball was immensely popular, but so were entirely unrelated extravaganzas at the city ballparks. In July 1925, for example, Aida was performed at Yankee Stadium, with live horses and a bored camel (not to be outdone, the Polo Grounds booked the Municipal Opera Company to perform Carmen in September, though without animals). In the Gold Cup Regatta in 1925, a 30-foot mahogany powerboat with a V-8 engine, built on City Island, returned the Cup to New York waters. She won the race in Manhasset Bay, Long Island, and her Gatsbyesque name was Baby Bootlegger.

"Baby Bootlegger" wins the Gold Cup, Johan Bull for The New Yorker, 1925.

Drinking mattered as much in Prohibition-era Manhattan as it did in East and West Eggs. In the month of Gatsby's publication, "The Talk of the Town" reported on a bootlegger called "the Yale Boy," who had made a fortune courtesy of a swift yacht and "London offices of distilling concerns." Having spent the fortune on hotel living, a titled lady, and gambling, the Yale Boy was reported to be plying the seas again. A regular feature near the end of each issue of The New Yorker in 1925, "The Liquor Market," listed what hard liquors and champagnes were available in town -- though it rarely printed from whom -- and what the prices were that week. Helpfully, the magazine reminded its readers during the summer of 1925 that Coney Island, where Gatsby wants to take Nick that steamy summer's day, was a good place to get drink.

Cartoons about drinking, and stories about drinking, were in just about every issue. When Babe Ruth managed to get his hands on a particularly generous supply of illicit beverages and appeared in public "bousing with more than the usual flagrance, in short, violently drunk," he was suspended for a week by Yankees manager Miller Huggins and fined $5000 -- earning top coverage in The New Yorker. In two glorious touches like Jay Gatsby's, Ruth insisted on pink pajamas when taken ill in Asheville, North Carolina, only two weeks after Gatsby was published; and, at a St. Louis hotel in the heat of summertime of 1925, Ruth "bought some twenty, bright silk shirts." When he checked out, "'They're yours,' said Mr. Ruth to the conscientious bell boy who ran after him with the collected garments." Perhaps The Babe, himself a poor boy on his own from youth who found wealth and immortal celebrity in New York and far beyond, who lived not merely like a young rajah but the Sultan of Swat, took a look at Fitzgerald's novel. Perhaps he found some things to like in its title character -- even if Gatsby might, reprehensibly, have been involved with Meyer Wolfshiem's fixing the 1918 World Series.

Princeton and Yale fans meet on "the bottlefield" at a football game, The New Yorker 1926

There were regular letters from "Tophat," telling women and men what to wear, and exulting in new, flourishing clubs like the Club de Vingt, "rivaled only by the Plaza Grill in its Scott Fitzgeraldism." The New Yorker reported who was lucky enough to be sailing for Europe, and who was to be seen or visited where. Even in the humor columns, Fitzgerald was noted in absentia. He might not have even been in New York when the magazine commenced, but who might one look for, on the trip from Paris to Rome? According to the "Speaking of Europe" column in April 1925, "the Fitzplasters" and "the Hemingnits."

The Great Gatsby was reviewed, snidely, in May 1925. "[Fitzgerald] still reveres and pities romantic constancy, but with detachment. Gatsby, its heroic victim, is otherwise a good deal of a nut, and the girl who is its object is idealized only by Gatsby[.]" The New Yorker did recommend Gatsby that summer in their "Tell Me A Book To Read" column (designed to direct readers to "a few of the recent ones best worth while"), but summarized it thus: "Quixote dismounts near Great Neck from a blind-tiger Rosinante, to sacrifice himself to a despicable Dulcinea." Other blurbs in the "Tell Me" during summer 1925 would call Gatsby the "Ugly-duckling emergence of a true romantic hero in North Shore Long Island high low life"; "a Yankee Quixote so fine as to be taken seriously"; and "a rough diamond of devotion and chivalry, cast before swine on Long Island." The New Yorker had to admit that Fitzgerald, the "grandfather of the Long Island flapper," had "ripen[ed] as a novelist" with Gatsby. However, the "In Our Midst" column that June couldn't resist noting that Fitzgerald, "disappointed in the Motherland's reception of the latest chef d'oeuvre," had been seen moping about Paris. Gatsby was off the recommended book list by the end of August.

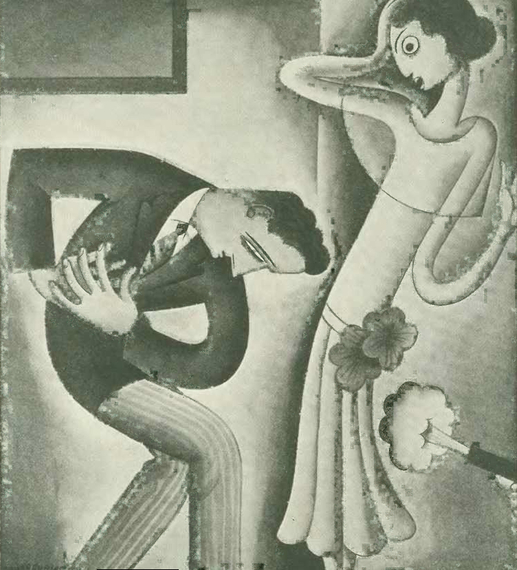

Gatsby gets shot while Daisy watches (Broadway version), The New Yorker, 1926

Little squibs, longer articles, and even cartoons in The New Yorker after Gatsby's publication nonetheless routinely paralleled its stories and themes. An inordinate number of the small illustrations at the bottoms of pages feature speeding cars, policemen in pursuit, and car wrecks. Gatsby is, of course, driven by car accidents of all kinds, as was contemporary New York. Traffic lights had just come to major American cities in the late nineteen-teens, and were often disregarded. On Long Island, the roads had three lanes -- a middle lane, intended as a passing and turn lane, was the inevitable site of dreadful head-on collisions. Both Scott and Zelda were bad drivers; in 1920 she wrote genially to Scott's old Princeton friend Lud Fowler that she had "ruined" their car "because I drove it over a fire-plug and completely de-intestined it."

Bad drivers, Peter Arno for The New Yorker, August 1925

Cars were dangerous, yes, but also beautiful. Henry Ford's famous dictum that a customer could have a car painted in any color as long as it was black would help lead to the demise of the first affordable American car, the Model-T, in 1927. Customers wanted colorful cars in the Jazz Age. The colors available were every bit as outrageous as Myrtle Wilson's chosen lavender taxicab; Caprice Rose, Pigeon Egg Blue, and Sea-Fog Green were among the colors of the cars on display in the showroom at the Hotel Commodore in November 1925. "Motor Caste," by Stanley Jones, in the 30 May 1925 New Yorker, is full of descriptions of cars that read like a parody of Jay Gatsby's "circus wagon" and its kin: "My eye was struck by a low, coffee colored car of tremendous length which thrust a long, pointed nose at us. Lamps like snare drums bound in silver flanked the boat-like prow, and the low leather top fitted close over the tonneau, like a girl's sport hat."

And, in a keen irony where Gatsby and Fitzgerald are concerned, a young Harvard lawyer named Charles Brackett published a novel, Week-End, right on the heels of Gatsby in the summer of 1925. Brackett's book is similar to Fitzgerald's in terms of setting and characters, a Long Island saga of decadence and lavish limousines, a wealthy hostess, and "a muscular young man and a determinedly coltish girl." I've read Week-End, and can't recommend it -- but The New Yorker gave it a rave review that September, dubbed Brackett "a rather surprising and shining debutant," and soon hired him as their drama critic. Week-End also got Brackett a job at Paramount as a screenwriter in 1932. Brackett would win three Academy Awards -- including one for The Lost Weekend, whose alcoholic writer hero Don Birnam loves The Great Gatsby -- and an honorary Oscar, as well as being president of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences during the 1950s. Brackett's collaboration with Billy Wilder was one of the great combinations during the golden age of movies. The easy success of Week-End in print, and Brackett in Hollywood, contrast vitally to the fates of Gatsby, at the time, and Fitzgerald in Hollywood. An admiringly inscribed copy of Week-End, to Fitzgerald from Brackett, was in Fitzgerald's library when he died.

When Fitzgerald suffered a fatal heart attack in Hollywood in 1940, The New Yorker memorialized him, dismissively once more, in "The Talk of the Town" on 4 January 1941. It was as if by dying young he had somehow proved them right. Though praising him for his beautiful writing, and regretting as a given fact that he was already becoming forgotten, they couldn't stop likening Scott Fitzgerald to Amory Blaine and Dick Diver, and diminishing him even in the act of commemoration: "The desperate knowledge that it was much too late, that there was nothing to come that would be more than a parody of what had gone before, must have been continually in his mind in the last few years he lived. In a way, we are glad he died when he did and that he was spared so many smaller towns, much further from Geneva."

© Anne Margaret Daniel 2013/Huffington Post

Images appear online via The New Yorker Archive, where the whole run of the magazine from February 1925 - present is available.

Please read my full article on Fitzgerald and The New Yorker in the Fitzgerald Society Review 2013, available now from Penn State University Press.