Over the last few days, I've read -- watched, listened and read -- "Piano Demon," the fascinating story of nearly-forgotten 1930s jazz pianist Teddy Weatherford as it unfolded on my iPad. In a pre-release version of The Atavist, I've glimpsed how we'll read as smart mobile devices become even more ubiquitous.

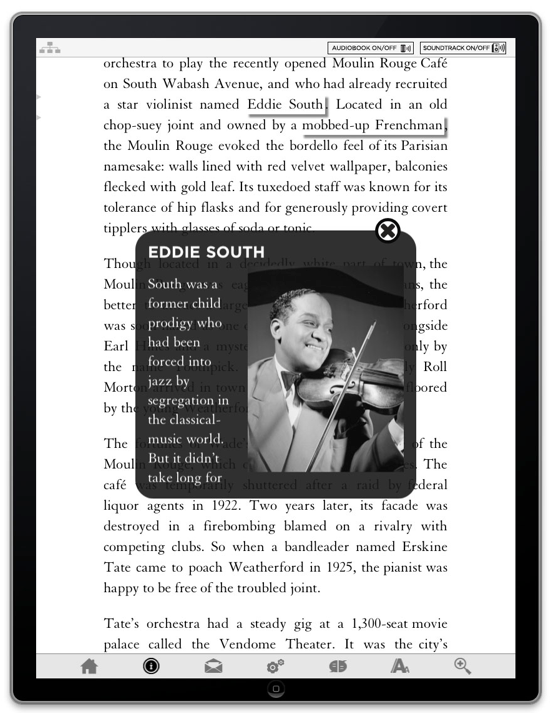

The Atavist is a multi-device reading app for presenting long-form nonfiction created by journalist Evan Ratliff, New Yorker editor and author Nick Thompson, and digital designer Jefferson Rabb. The Atavist will launch this week on iTunes for iPhone and iPad and a slimmed-down version for Kindle, with Nook and Android versions to follow soon. The free app presents the first two stories for purchase at $2.99 each, Wired journalist Brendan Koerner's "Piano Demon" and Ratliff's own bank-heist narrative, "Lifted." Atavist stories are researched and reported by experienced journalists and editors, and make full use of their digital platform by including "in-line extras" such as video, audio, interstitial images, timelines, character bios, maps and definitions. The stories include musical soundtracks where appropriate (with a mute option), and can be experienced as audiobooks with author readings (a neat scrolling feature lets you toggle between audio and text without losing your place). It's already attracting notice, with dual interviews with Ratliff and Rabb in Fast Company, and a short profile in Business Week.

Rabb's app design is a model of concision and elegance, with page elements that unobtrusively reveal the "extras" and options to personalize the reading experience. Each story receives its own design based in the content, making it a unique product while integrated into the Atavist format. The story structure and interface reflect its primary home on the iPad and iPhone. Stories are chaptered, which allows interstitial content between chapters and gives the narrative natural rests, perhaps a recognition that some mobile readers will access the story in short bursts. The stories progress through the chapters with horizontal swipes and the text of each chapter scrolls downward. I'm told by Rabb that this user experience remains somewhat controversial among the team. I think it rightly reflects the gesture inherent in the device and user behavior rather than nodding to a legacy of horizontal flipping inherited from print.

The Atavist founders describe their endeavor as "a boutique publishing house producing original nonfiction stories for digital, mobile reading devices." And that raises the question of what it means to be a publisher now. The Atavist essentially combines a storefront for individual stories with a proprietary content-management tool called Periodic. The Atavist "store" exists comfortably within the larger iTunes marketplace, an environment that taught consumers to purchase music, tv series or games by individual song, episode or app. Periodic allows editors to easily, intuitively assemble stories and then push them to the various mobile formats at once. The tool re-formats text, layout and media for the opportunities and limitations of each device. The Atavist team therefore concentrates on finding, commissioning and presenting intriguing stories, without the people and infrastructure required to physically package, manufacture, sell and distribute - activities that occupy the majority of publishing employees. In other words, The Atavist partners get to do the fun stuff without the complexities and expense of print publishing.

The seminal insight that led to The Atavist came from Thompson and Ratliff's work in magazine journalism, and their frustration with print's space constraints. Instead of digital's limitless territory, print magazine pages are scarce, high-priced real estate whose availability is largely driven by the success or failure of the ad-sales staff. And short books cost nearly the same to produce and deliver as longer works, while being less welcome in the bookstore. Thus The Atavist's digital-only model promises to revive the 10,000-plus-word nonfiction magazine feature and the nearly-extinct novella-length book. Unbound, stories expand to their ideal length with accompanying digital features that enrich and guide. Each story finds its reader without struggling for attention with departments, lists, photo features and ads. Many magazine apps feature dazzling design and technology. But most borrow their print forerunners' reliance on readers grazing through a buy-it-all buffet when the consumer increasingly expects to "playlist" digital bites, sampling individual stories, songs, tv episodes or streaming movies. And readers now expect to be part of the creative process; Atavist stories will be updated if the story evolves and may soon accommodate comments and reader participation.

In addition to writers hungry for a paying outlet for long-form journalism, the Atavist partners have met with a long list of curious magazine and book publishers. Here's what the publishers saw: nimble digital programming and design for mobile devices, today's fastest-growing platform; attention to and investment in content, not infrastructure and personnel; and seamless user experience and commerce designed for how we buy and read, based on iTunes, Amazon and Android, not a palimpsest of pre-digital legacies and web experiences. Magazine and book publishers could find worse roadmaps to the future.