At long last, the 2016 presidential primaries are (mostly) over. Before anyone breathes a sigh of relief or imagines that we'll get a break before the general election campaign kicks into high gear, forget about it. The 2016 presidential campaign will continue to swirl around democracy's drain. By November 9th--the morning after Hillary Clinton or Donald Trump is elected as the 45th of the United States--we'll all just be glad it is over. And, by January 2017, the 2020 race will have already begun.

Before we become too undone about the 2016 train wreck, we thought we might offer a simple reminder. Dissatisfaction with the process, the candidates, and the outcome is a defining characteristic of American politics. 2016 is likely to be special, but it will be a difference in degree rather than kind.

The Broken Process: Let's start with the process. In 1994 in his now classic book, Out of Order, Harvard political scientist Thomas Patterson offered a simple solution for fixing our electoral process: Shorten it. The length of the presidential campaign assured the electorate would grow weary of the election long before the final ballots are casts.

The media, Patterson argued, were largely to blame though not entirely at fault. Thanks to the oddity of the U.S. nominating process, U.S. elections were increasingly structured around the media rather than the political parties. As a result, the long campaign process and journalists' penchant for objective "game frame" news stories focused attention away from the issues and toward the horse race while the media's anti-politics biases assured voters were exposed to large doses of negative and cynical press coverage. In those rare moments when issues were covered, they were treated--not as the result of careful deliberation--but as an attempt to cynically manipulate voters.

Much has changed since 1994. The media system has been transformed by the growth of digital media and an increased choice in media content. Simultaneously and not coincidentally, the political parties have been neatly sorted into competing ideological camps. The affective distance between Republicans and Democrats has widened as the number of conservative Democrats and liberal Republicans has dwindled to near extinction.

These changes might have made for more sensible, issue-based campaigns. This, however, was not to be. First, as the Trump campaign powerfully illustrates, media decisions regarding news coverage may have played an even larger role in the 2016 primaries than in previous Republican election cycle. By some estimates, Trump received the equivalent of $2 billion in earned (or free) media coverage overwhelming the fundraising, political experience, and partisan networks of his opponents.

Second, the capacity of unlimited news coverage might have allowed for greater issue based news coverage of the candidate while also altering the balance of positive to negative tone in news stories. Instead, it appears to have primarily opened the door for unlimited partisan screeds and click bait headlines. Consider, for example, this non-random sample of news stories on the frequently visited political websites.

- Trump Change: Donald Short on Cash (Huffington Post)

- Newt Gingrich has a Theory about why Sanders is still in the race (The Blaze)

- Trump Full-Speed Ahead: "Feel like I am 35" (Drudge)

- Romney: Trump Will Inspire Trickle-Down Racism as President (News Max)

- 5 numbers that matters this week (Politico)

- American cynicism is reaching a boiling point and the electoral system is to blame (Salon)

This selection of stories is immediately self-serving but hopefully it illustrates the larger point. There is little in the news coverage of contemporary political campaigns to inspire confidence in the political system, the candidates, or the eventual outcome. The audience demands that long made the news media a poor vehicle for structuring campaigns have only grown as competition has intensified, assuring a constant barrage of negative, personal, and mostly issue-less news. Even if the process yielded better nominees (however one might define such a term), a substantial proportion of the voting public would still be unhappy about the process and the choices.

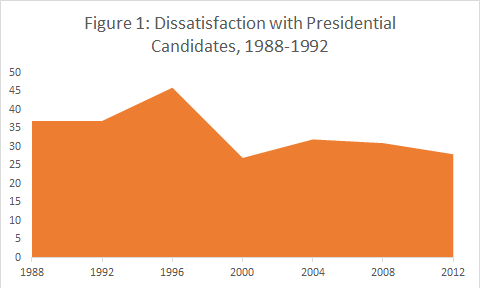

Unlikeable Candidates: Dissatisfaction with the candidates is nothing new. In most years (see Figure 1), roughly a third of voters express dissatisfaction with their final choice of candidates just prior to the election. In 1996, nearly half (46 percent) of voters said they were dissatisfied with the decision between Bill Clinton and Bob Dole.

2016 is still likely to be special. The last candidates standing - Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton - are not just widely disliked, they are the most widely disliked major party nominees on record. Consider that based on most recent polling data, 56 percent of voters have an unfavorable opinion of Hillary Clinton. This would be remarkable if she were not running against Donald Trump, a candidate viewed unfavorably by 59 percent of voters. Indeed, Hillary Clinton's most effective campaign appeal will be that she is not is not Donald Trump. The same will also be true of Trump. In this election cycle, voters will be primarily voting against (rather than for) candidates.

This is not, however, as unusual as it sounds. In 1966, V.O. Key famously noted that "the people only vote against, never for." Within political science, much scholarly attention has been paid to negative or anti-candidate voting. Midterm election cycles, for example, are driven largely by out-party voters who turnout in greater numbers to cast a ballot against the in-party president (but see Fiorina & Shepsle for evidence that this is an artifact). Modern campaigns are similarly built on the principle that voters suffer from negativity biases in how they allocate attention and make decisions. As a result, negative campaign appeals are often thought to be most effective in moving the day-to-day polling averages. Finally, studies of previous election cycles have found (based on self-reports) high levels of voting motivated by a desire to vote against a candidate. The high-water mark in these studies was 1980 when 46 percent said they were motivated to vote against Jimmy Carter or Ronald Reagan. In 1964 and 1984, by comparison, negative voting was much lower (30 percent) but still accounted for nearly one of every three votes cast.

Overall, what is special about 2016 is not that negative voting will occur. It's the number of voters who will cast a ballot not to promote a candidate or issue position but primarily to keep the other side from winning. Such high levels of negative voting will likely further influence attitudes about the fairness of the outcome.

Unfair Outcomes: Election night losers are not only typically unhappy with the result, they often believe the process itself was rigged. If only the game were fair, their side would have won. They similarly express less trust in political institutions and--more broadly--in the political system.

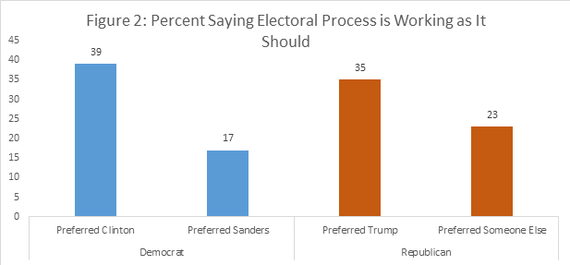

Bernie Sanders' supporters provide the best example from the 2016 primary season, believing the cards were stacked against him from beginning. (see Figure 2). Curiously, these perceptions hold even in light of evidence that Clinton won the most votes, pledged delegates, and unpledged superdelegates; despite the fact that Sanders' only recently claimed an affiliation with the party he is was trying to lead; and even though some rules (e.g., low turnout caucuses) clearly favored his campaign.

Sanders supporters are not entirely unusual. Existing studies have linked winning (or losing) with satisfaction with democracy, and have also noted that candidates play an important role in perceptions of the fairness of the process. With Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump each claiming the other is unfit to serve as president, the 2016 election may also be notable in its long term consequences in terms of support for democracy.

A Choice of Scoundrels: Democracy, by its very nature, is deeply dissatisfying. It not only requires a citizenry mature enough to realize that one side never wins all the time but also that they will often have to make imperfect choices between undesirable options. Turning to V.O. Key yet again, "when given a choice of scoundrels they will likely pick one." This is the nature of democracy: Even when the choices are not very good, the decisions are ours.