Political scientists have long struggled with understanding American political parties. For years, we wrote that they lacked ideological structure and organizational capacity. We looked with longing at European political parties which painted issues in cleaner partisan lines, structured vote choice, and mobilized the working class. This European party envy was perhaps best expressed in the American Political Science Association's Committee on Political Parties 1950 report "Toward a More Responsible Two Party System."

Then Newt Gingrich happened, and American parties began a process of sorting neatly into well-defined ideological camps. In light of this new reality, political scientists quickly pivoted and lamented the inability of parties to govern. The American political system built on checks & balances and separation of powers required political parties that were less rigid and more open to compromise. European style parties just didn't work very well within a Madisonian design. Norm Ornstein and Thomas Mann chronicled this shift in "The Broken Branch" and then declared in a follow-up that partisan polarization "was even worse than it looked."

In 2016, Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders provide yet another twist in this evolving story line. Both are contenders for their party nominations despite rather sordid histories of partisan infidelity and, at best, weak connections to their current party's organization and leadership. Not long ago, Trump claimed to be a Democrat (and/or an Independent) rather than a Republican. And, while Sanders might have caucused with Democrats, he kept them mostly at arms' length, working with them when convenient but never fully embracing the cause.

Their primary success reminds us that--despite our recent flirtation with responsible parties--nominations remain outside of party control and the meaning of a party label is fluid and subject to change with each new election cycle. Sanders is a Democrat and Trump a Republican for no better reason than that they say they are.

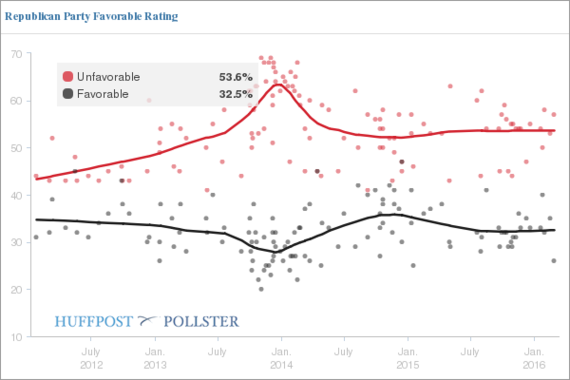

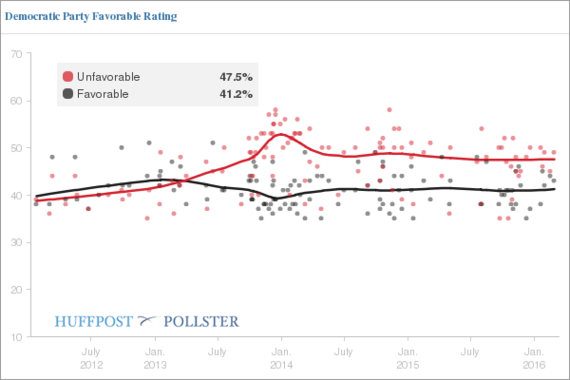

Their success is also a reminder that--even if party labels help to define political identities, structure political attitudes, and guide political behaviors--we aren't particularly fond of parties as organizations. Neither party enjoys very strong favorability ratings, especially when the party is explicitly linked to Congress. Republicans in Congress are held in particularly low esteem.

Recently, political scientist Howard Gold summarized trends in public attitudes toward political parties and party systems. The following findings are particularly noteworthy for current purposes:

•The percent of Americans with favorable views toward the Democratic and Republican Parties has declined significantly. In 1997, 60 percent of Americans had a favorable view of the Democratic Party. This dropped to 46 percent in 2014. Over the same time period, Republican favorability declined from 57 to 37 percent.

•Americans are more likely to see "important differences in what the Republicans and Democrats stand for" today than in the past. In 1996, 64 percent of Americans said there were important differences in the parties. By 2012, this had increased to 81 percent.

•Since 2003, the percent saying the Republican and Democratic Parties do an adequate job of representing the American people has declined from 56 percent to 26 percent.

Overall, we are more negative toward parties, see them as more polarized, and less effective in representing our preferences. Paradoxically and simultaneously, however, partisans have become increasingly disgruntled with their own party for not remaining adequately committed to core "conservative" or "liberal" ideological values.

Within this context it should come as no surprise that presidential candidates running against the party establishment are enjoying success. Running against the party is not, historically, a unique phenomenon. Eric Cantor's loss to David Brat (described in Slingshot by Bell, Meyer, & Gaddie) is illustrative of Tea Party take-downs of establishment politicians over the past several years. These challenges have typically come from the right and self-described "true conservatives," and have been aimed at elected officials believed to be too accommodating, too willing to compromise, or too corrupted by Washington.

What is unique about 2016 is the potential for a GOP infidel rather than jihadist to destroy or recreate the Republican Party brand from the top down. The Sanders' campaign is similarly more of a coup aimed at toppling establishment leaders than a grassroots revolution.

We won't know the full effects of these campaigns until we know the outcome of the 2016 elections. What we do know - with all due respect to Stephen Wayne - is that this is no way to run an election. Since 1968, nominating processes have been ceded to rank and file caucus-goers and primary voters, opening the door to entrepreneurial outsider candidates willing to challenge the party establishment and giving undue influence to voters in early primary and caucus states.

We can debate how well this system has worked in prior presidential elections but the 2016 election cycle has been a case study in a broken presidential nominating process. It is past time to revisit the rules, give the parties greater control over who can compete for party nominations, and shorten the length of the primary season.