We've started talking about mythology in painting, and I've been wanting to talk with you about Kyle Staver for a while, and she paints a lot of Greek myth paintings, and she has a show opening on Thursday at Tibor de Nagy Gallery, so there you go. Good fortune all around.

My feeling is that lately, we are accustomed to much too glossy and detailed a concept of the myth-image. This trend begins, I would suggest, with 19th century English painter Lawrence Alma-Tadema.

Lawrence Alma-Tadema, "Unconscious Rivals," 1893, oil on canvas, 18" x 25"

He's not painting myths per se, but his paintings of the classical world are apropos. Stripping classical history paintings of the melodrama and flights of fancy of the Renaissance and Baroque, he applies the enlightenment hope that knowledge can become total, that every single thing can be known. His paintings of Rome deploy an anthropological and archaeological rigor which were the state of the art of his age.

He was not the only one of his kind, but he was the master of the genre. His detailed, daylit view of antiquity persisted through our own century, in the confabulations of the silent age of Hollywood, and in the astonishing accomplishments of fantasy illustration.

D. W. Griffith, still from the film "Intolerance," 1916

What began as a heroic battle against the loss of memory and history has ultimately degenerated into the cloying, massless digital environments of the most recent Clash of the Titans movies. Here we find a dead end of the Alma-Tadema impulse. We discover that one form of knowledge precludes another, that to know all things born of brightness and identification is to forget things born of darkness and mystery.

Another lesson we learn from this degenerate retelling of myths is that the myth-image is not entirely rooted in the land of brightness and identification. The myth-image cannot be resolved; we cannot touch the face of Zeus as we can those of our human brothers. Sunlight does not make his features clear. There is a light that lights him, but we do not have the eyes to see that light. We will when we become gods. We are not gods yet, and pretending that we have their awful sight does not allow us to see. Rather, it cheapens our souls' turning toward the things we thirst to see. The visions these pretenses provide are trinkets rather than treasures. On Olympus there is an utter light, but down here the gods are shrouded in darkness and mystery.

One solution is to paint the gods as mortals see them. How do mortals see them? Indistinctly and murkily, by moonlight, with the aspect of a rustle among the leaves or a burst of feathers. A thing blurs past us, and by the time we turn to look at it, it is gone. This is how Kyle Staver paints the myths. Examine her painting of Daphne:

Kyle Staver, "Daphne," 2013, oil on canvas, 70" x 50"

Daphne was the daughter of a river god. Apollo fell in love with her and pursued her. She hated him and fled, but he was faster. She cried out to her father to save her by transforming her. So he turned her into a tree just as Apollo caught up with her. It was a laurel tree. Apollo's laurel wreath comes from the tree he loves.

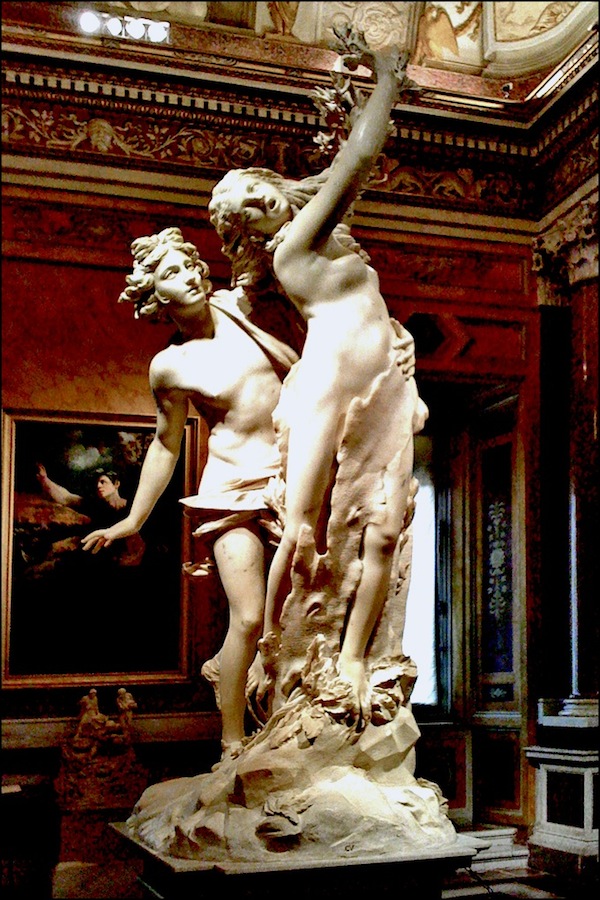

Staver is not the first person to come up with the clever idea of making art from this myth. It just so happens to be the subject of one of the finest sculptures ever executed:

Bernini, "Apollo and Daphne," 1622-25, marble, 96"

This sculpture hails from an age when the fruitful progress of knowledge had not yet degraded unselfconscious faith. Bernini, in the full glare of his own brilliance and arrogance, made a sincere "Apollo and Daphne." He saw them very nearly with the eyes of a god.

Staver has a different thing to contribute. Her painting is not about gods looking at one another, but about humanity looking at the gods. Painting with imperfect mortal eyes, she ruminates on how human beings understand the divine. Her picture plane is a flattened semiotic space, floating and chaotic like a cave painting. She says that we see the gods with the cognition of childhood: the childhood of our species and ourselves. Her figures are simplified and emptied out, indicated by illustrative marks which make clear what they are and what they do. She says that we anthropomorphize, just barely, something which is essentially inhuman and unseeable. And her scene takes place in a luminous darkness. It is not the complete dark of blindness, but the breathing, expectant dark of the full moon, when light appears in unexpected corners, catching flashes of things -- a paw, tree trunks, Daphne's breast and hip and sprouting leaves. This light, more than anything, is what I respond to in her work.

It is a dense, milky light, as if filtered through water or glancing in from another room. It lights very little but itself. It is a dreamy light, a separate active entity. It transforms the aspect of a scene from the physical to the transcendental. It is the light of Olympus, diluted so much that mortals can perceive it, and perceiving it, find that it is like a whisper or a glimmer in the woods.

Observe how much Staver gives up in exchange for this light: her composition is flooded with darkness, so that the light can glow. She overpowers the natural human impulses to know and to depict with a counter-strategy of obscuring and elliding. She can draw gracefully, but instead she draws crudely. If her drawing were graceful, the light would emerge naturally from it. It would be a rational light. But this rationality would destroy its uncreated divinity. So she must draw crudely, in exchange for the independent life of her light.

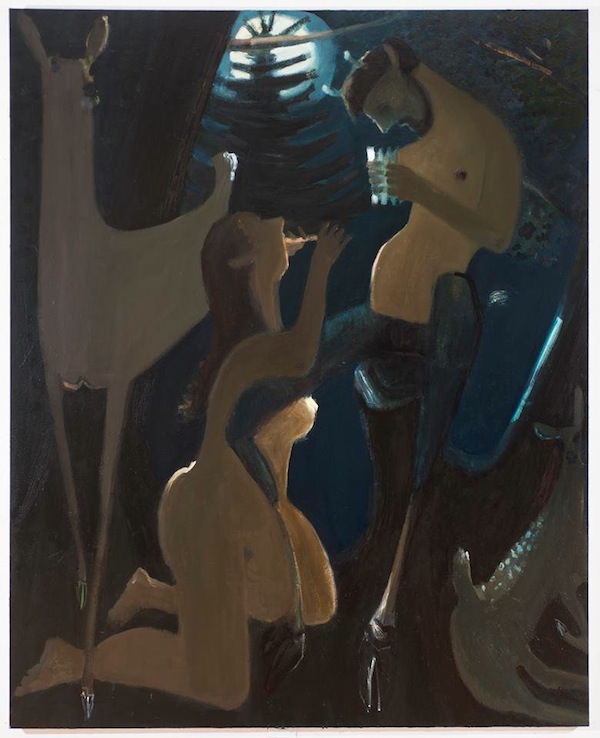

Kyle Staver, "Syrinx," 2013, oil on canvas, 68" x 52"

Here she depicts the myth of Syrinx, who had a problem with Pan not too different from Daphne's problem with Apollo. Syrinx got turned into water reeds for her troubles, and Pan cut them and made his pan pipes from them. We have looked at what Staver gives up for her light. But looking at this painting in addition to her "Daphne," we see more of the universe she gets in exchange.

First, and most obviously, Staver's light gives her work sexiness. It is filled with erotic portent. Light traces out some zones of desire, and leaves others achingly implied. Her night is a humid night loud with crickets and bullfrogs. The territory of the erotic spreads beyond its familiar hotspots until the entire scene is subsumed in it.

Less obviously but more profoundly, Staver's light is the medium through which felicitous synchronicities enter her work. What I mean by this is that when an artist finds their personal region of rightness, good things they did not intend or imagine happen of their own accord in the work. Rightness and strangeness go together this way. It is a form of magic. In the case of Syrinx, the full moon behind the pine reads, for an instant, like sharp teeth in the opened mouth of a predator. There is a shock of threat before the scene rights itself, and the echo of the threat remains, shining down on Pan and Syrinx. The violence of the scene has fallen out of Staver's depiction, except in that wolfish moon.

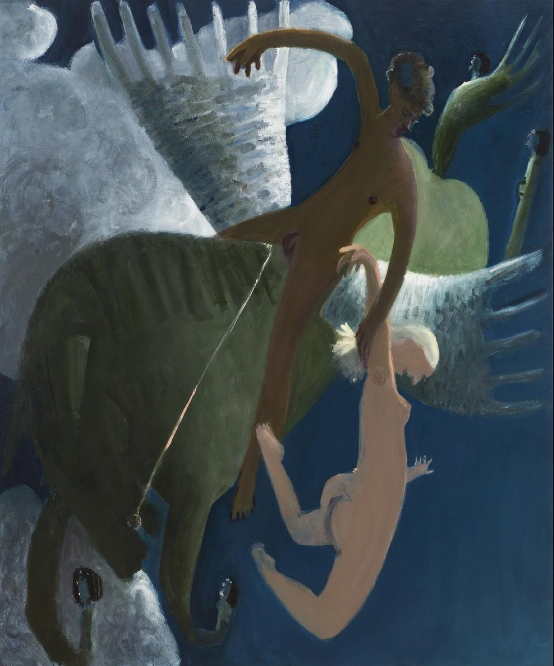

Finally, consider her "Andromeda":

Kyle Staver, "Andromeda," 2013, oil on canvas, 68" x 52"

Again we see the elements which repeat throughout her work: the floating vertical chaos which propels her figures into flight -- an ambivalent attraction to extremely literal male/female power struggles -- the frank reveling in familiar erogenous zones (top to bottom: nipple, penis, breast, ass) as well as the erotic bleed into surrounding territory -- and that phenomenal light, the enchanted indirect light that leaks in from the hallway after bedtime.

Notice here the massy clouds, and the brilliant trick Staver has used to preserve her high-contrast regions of dark and flashes of light: it is daytime but the blue sky is turquoise fading to navy and royal. What manner of day is this? It is the day of the thinnest atmosphere, day as seen from the mountaintop, the jet plane, the rocket ship.

Staver's mythology is native to the age of Pan Am and NASA; she reclaims the brutal Greek theophany -- the glimpse of the god -- in the context of the split atom and the integrated circuit. There are a hundred roads to Olympus. Staver's road may not be the one you would prefer. But in my opinion, we have not been the same since we lost what Olympus offered, and I'm glad Staver is out there with her machete, hacking her own winding, authentic path back through darknesses and mysteries to the house of reason, of ruthless beauty, of blinding visions and ideas greater than we are.

---

Kyle Staver: Recent Paintings

October 17 - November 23

opening reception October 17, 5 p.m.-7 p.m.

Tibor de Nagy Gallery

724 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY, 10019

Alma-Tadema, Bernini, and Griffith via Wikimedia Commons

all other images courtesy Kyle Staver