Predicting elections is tricky. Polling has come a long way from its early failures, but it can still go spectacularly wrong. When polling-based prediction actually succeeds, we're cautioned about relying on its success, sometimes to the extent of predicting the failure of predictions.

Wouldn't it be nice if we could dispense with all polling's expense, effort, and risk? Maybe there's a group of people so in-tune with the electorate that they could do the predicting for us?

That's what bellwether counties are for!

These mythical places come to prominence in every electoral cycle, most recently in On the Media's segment "Magic" Terre Haute. OtM reports on Don Campbell's investigation of Vigo County, Indiana which has "voted for the winning candidate in every presidential election except two -- 30 out of 32 elections", and has not "missed in 60 years". According to Campbell, "No other place in America comes close." According to Bob Garfield, they're "history's most reliable presidential bellwethers".

Does Vigo County really predict how the nation will vote? To find out, I collected county-level voting data from ICPSR and the Congressional Quarterly Voting and Elections Collection, covering the period 1840-2012 (code available on GitHub, there are some disagreements between these data sources and Dave Leip's US Election Atlas).

Which are the bellwethers?

It's true that Vigo hasn't missed since 1952, but neither has Valencia County, NM. These two counties are far from outliers: fourteen other counties have only missed one of those elections.

Looking back further, on elections since 1840 Vigo County is an OK predictor but there are nine other counties that do just as well. Racine County, WI might be the single best bellwether: if it called all the elections with missing data elections correctly, it would have 86% correct.

Also, spare a thought for Webster County in Georgia. Since its founding in 1853 it has only got 13 out of the 37 extant elections right. That makes it a somewhat reliable an anti-bellwether: if you picked the opposite of Webster's vote, you'd do better than siding with 75% of other counties with as much data.

What good are bellwethers?

Google Scholar reveals surprisingly few papers about Presidential election bellwethers. Perhaps the best is this 1975 paper by Tufte (yes, that Tufte) and Sun. It concludes that bellwether status can only reliably be assigned after the fact.

This is a common problem for predictive endeavours: it's trivial to tweak your predictive machinery to predict the something that's already happened. Once you've predicted the past, you can also easily tell yourself that you could have done so before it happened.

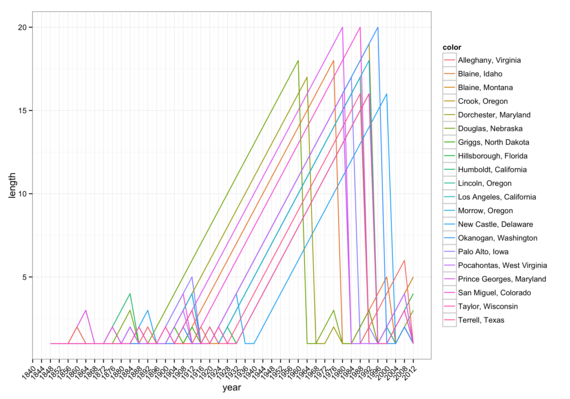

We can extend Tufte's analysis to our larger data set. For simplicity's sake, we'll look at counties that have had -- at any point in time -- the same 60-year/15-election streak that Vigo currently enjoys.

Take 1968, for example. Northampton, PA and Prince George's, MD (as well as four other counties) had predicted the correct result in every election in the preceding 60 years. But in the next election Northampton voted for McGovern and Prince George's voted, accurately, for Nixon. There are 90 cases where a county had a streak of 15 correct predictions going into an election year (for 43 distinct counties). But in 47% of those cases, the county failed to get the next election right. That's pretty close to a coin-toss.

This graph (click on it for a bigger image) shows the performance of the 20 counties that have ever had a streak longer than Vigo's. It's something between a fluke and a post-hoc selection that Vigo is the only county with a 60 year streak right now. But we shouldn't expect it to continue.

What is a bellwether anyway?

So far, we've worked out that bellwethers aren't particularly great at making predictions, and Vigo isn't the only contender. But how are they supposed to be making predictions in the first place?

Bellwethers are claimed to be demographic and attitudinal microcosms of the US as a whole, meaning the majority of the their population chooses the candidate who becomes President.

This justification is suspect given the way US Presidential elections work, namely: the winner of the majority popular vote is not necessarily the winner of the election. Even if a county was a perfectly representative sample from the whole population, that's not sufficient to predict all elections, a true bellwether's majority would sometimes have to go against the popular vote.

This isn't just a specualtive question: in 2000, a majority of voters in Vigo County voted for George Bush -- but the winner of the nationwide popular vote was Al Gore. Vigo's residents somehow got the election right while getting the popular vote wrong.

Is there really a plausible mechanism which could be causing bellwether citizens to predict the distinctly non-proportional outcome of the electoral college -- taking into account Maine and Nebraska's Congressional district method, faithless electors and the Huntington-Hill method?

Conclusion

In machine learning, best practices require strict separation of the data you predict with (the training set) from the data you evaluate with (the test set). Without this, it's easy to over-fit: to produce a model that can perfectly predict what has already happened but does not generalise to the future. When you've only got 57 observations -- and you have to wait four years to acquire another one -- maintaining that discipline is hard. That's at least part of the story with bellwethers too. They're not great predictors, except in retrospect.

But bellwethers still matter -- if we don't care solely about predictive power. We can certainly learn something by studying a small town in detail, as from the Middletown studies. However, these findings can't be generalised in the (relatively) straightforward statistical way that a random sample can be. We can learn from Vigo, Valencia, York, Racine, and Strafford. But to do so, we'll need to make use of well-informed and sensitive interpretation, which, by the way, a documentarian like Campbell is well-placed to develop.

On the Media was looking for alternative to pundits. As it turns out, bellwethers aren't a alternative to pundits. They're another talking point.

A longer version of this post appeared at adamobeng.com