The Battle of Jutland

At the onset of World War I, there were a series of naval battles throughout the world's oceans that saw the Royal Navy largely destroy the German Navy's surface combatants outside of the Baltic Sea. For the bulk of the conflict, the war at sea revolved mostly around anti-submarine warfare. Germany used its U-boat fleet to sink Allied shipping in the hope that it could starve Great Britain and drive it out of the war. The British in turn deployed the Royal Navy to protect the convoys of merchantman bringing in essential supplies and to hunt down and sing the German U-boats.

The most significant large scale fleet action of the war would finally come in the spring of 1916. The Battle of Jutland/Battle of Skagerrak was one of the epic naval battles of all time. A popular aphorism at the time was that the Admiral of the Fleet, John Rushworth Jellicoe, "was the only man who could lose the war for Great Britain in an afternoon." The Battle of Jutland would offer an opportunity to do just that. It opened on May 31, 1916 and ended with both Britain and Germany claiming victory.

The Commander of the German High Seas Fleet, Admiral Reinhardt Scheer, was intent on making a sortie against the British coast in a demonstration of German naval power. He was confident that his plans were unknown to the main British battle fleet based at Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands, and that he would be able to carry out his sortie and return to Germany before the British Fleet could engage him.

His confidence was misplaced. The Royal Navy had broken Germany's naval codes. Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, able to read Scheer's messages, knew exactly what he was planning. Scheer was not looking for a decisive naval action, simply a propaganda victory to showcase German naval strength. The Royal Navy, offered the opportunity to ambush the German Fleet, quickly prepared for their most important fleet action since Trafalgar.

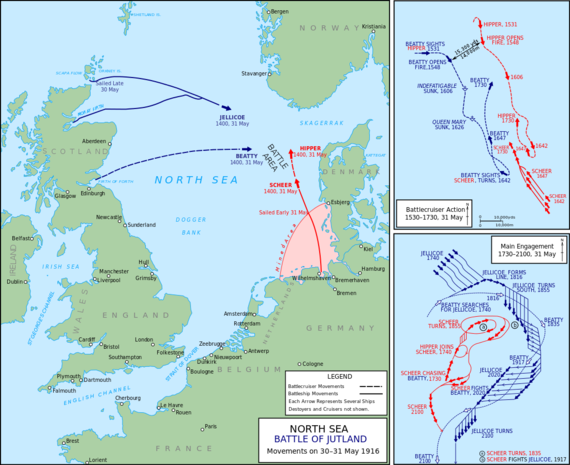

On May 30 the Grand Fleet put to sea. The 1st Battlecruiser Squadron under the command of Admiral David Beatty, leading the way from the Firth of Forth with six battle cruisers, four fast battleships, fourteen light cruisers and twenty-seven destroyers. The main British force, consisting of twenty-four battleships, three battle cruisers and fifty-one destroyers under Jellicoe's command, came from the Moray Firth and Scapa Flow.

On the same day more than one hundred warships of the High Seas Fleet left German ports. The German fleet was split into a main force under Scheer and a scouting force under Admiral Franz Hipper consisting of five battle cruisers, five light cruisers, and 30 torpedo boats. German torpedo boats were roughly the equivalent of a Royal Navy destroyer. The German Fleet also deployed Zeppelins to patrol over the North Sea.

Positions of British and German fleets at the Battle of Jutland, May 31, 1916

Beatty's orders had been to scout ahead of the main British fleet to a point 230 nautical miles, east of Britain and then turn north to join Jellico's main battle fleet. At 2:20 p.m. the following day, May 31, the British and German cruiser squadrons sighted each other off the Danish coast at Jutland and opened fire.

Having made contact with the British Fleet, Hipper, turned his German cruiser squadron south to re-join Scheer's main force. In a running battle, with Beatty charging after Hipper, the British Admiral made a classic military blunder. He split his forces; signaling his faster cruisers to steam ahead and engage Hipper while his slower battleships would follow. Meanwhile, as if anticipating his subordinate's poor decision, Jellicoe had detached three of his fastest cruisers to rush to Beatty's aid.

As Hipper and Beatty fought their way south, the British lost the battle cruisers Queen Mary and Indefatigable to superior German gunfire. The loss prompted Beatty to remark to his Flag Captain, Ernie Chatfield, on the bridge of the HMS Lion, "There seems to be something wrong with our bloody ships today." Just after 4:30 p.m. he received an unwelcome message from his scouting destroyers: the main German High Seas Fleet of sixteen battleships, six older pre-Dreadnought battleships, six light cruisers and thirty-one torpedo boats was surging towards him.

Under a screen of destroyers, Beatty now turned north in order to link up with the approaching Jellicoe. As he steamed north at full speed, fighting a rear guard action with significant losses, the three fast cruisers detached earlier from Jellicoe were steaming south. They missed Beatty's retreating force through a navigational error. Instead, in foul weather, which helped screen them, they arrived off the right flank of the German main force. In one of those fortuitous events on which great battles sometimes turn, they caught the German fleet by surprise; badly mauling the screening cruisers.

It was now the turn of the Germans to become confused. Scheer received an erroneous report from his right flank that an "enemy force of numerous battleships" had been sighted. In response, he turned to meet the threat. This put him perpendicular to the main body of the approaching British fleet. Shortly after 6:00 pm. the main forces of the Grand Fleet and the High Seas Fleet engaged.

Though initially obscured by smoke from Beatty's retreating warships, Jellicoe managed, with his greater speed, to "cross the T" of the German main fleet twice, sending broadside after broadside at the column of enemy ships. The "crossing of the T" was a classic naval maneuver where an attacking force approached perpendicular to an enemy fleet, allowing it to bring all its naval guns to bear on the lead elements of its opponent.

Scheer finally ordered the High Seas Fleet to retreat and to steam south to its German ports. Jellicoe attempted to overtake it before it could reach the safety of its own minefields. As night fell, despite a series of bitterly fought individual battles, the bulk of the German ships managed to evade Jellicoe's fleet and reach safety.

The British had lost fourteen ships, while eleven German vessels had been sunk. A total of 8,500 sailors had perished. Both sides claimed a victory. Though British naval supremacy had been severely dented, the German High Seas Fleet never again ventured out in force to challenge the Royal Navy during World War I.