Waterloo and the Road to World War I

Two hundred years ago this month, on June 18, 1815, on the field of Waterloo, in what is now Belgium, a French army under the command of the former Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte was decisively defeated. The victors were a pan-European force, the Seventh Coalition, under the overall command of British Field Marshall Arthur Wellesley, the First Duke of Wellington, supported by Prussian troops under Marshall Gebhard von Blucher. The defeat ended once and for all Napoleon's ambitions for mastery of Europe.

Waterloo along with Sarajevo would frame a century of overwhelming European power and influence in the world. It would see the conquest and colonization of much of Africa and the Asia-Pacific by various European nations, a second industrial revolution and unprecedented technological innovation that would transform daily life, and the emergence of what today we think off as the "modern world". Indeed, the 19th century would prove to be the most transforming century in human history, exceeded only by its progeny, the 20th century. World War I would mark the end of the peace that began with the victory of Waterloo and the beginning of a cycle of unprecedented violence and destruction which framed the 20th century and whose legacy reverberates to this day.

The peace that followed the Congress of Vienna, the Pax Britannica or the British peace, did not end war on the European continent, but it did buy a measure of stability. By creating a system of checks and balances, backed with Great Britain's money and the powerful Royal Navy, while ostensibly remaining neutral, London insured that no single European power would emerge to dominate the continent and risk another all-out war.

In the words of British Prime Minister, Lord Palmerston, "We have no permanent allies, we have no permanent enemies, we have only permanent interests." Preventing the emergence of a dominant European power was at the core of those permanent interests. For just over a century, Europe was spared the destructive, continent-wide wars that had dominated its politics for almost three centuries previously. The ambitions of would be conquerors, from Phillip II of Spain, to France's Sun King, Louis XIV and finally Napoleon Bonaparte, had been checked for good. Or so it seemed.

The Rise of Prussia

Prussia, a small German principality on the periphery of Western Europe, was an unlikely candidate to aspire to the mastery of Europe. Located on the north German plain, it was poor, predominantly agricultural, with few natural defenses. To the west and south were a bevy of small German duchies. It was vulnerable, however, to its larger neighbors. These were two formidable powers, Poland to the east and Sweden to the north. Beginning in the eighteenth century, Fredrick William I and then his son Fredrick II began transforming their Prussian kingdom into a major military power.

The ambitions and actions of one man, Otto von Bismarck, would transform Prussia into a German empire stretching from the Rhine in the west to the Oder in the east, and from the Baltic to the foothills of the Alps. As Prime Minister of Prussia, and later as the Chancellor of the German Empire, Bismarck figured large in European politics from the 1860s until his dismissal by Kaiser Wilhelm II in 1890. It was Bismarck who, by intrigue and warfare, succeeded in creating the Empire out of a loose collection of confederated German states.

His first step, in 1866, was to reduce Austria's influence as the most important Germanic state by drawing it into a war over disputed territory in the duchy of Holstein. The seven-week war was fought between the Austrian Empire and its allies in the German Confederation and the Kingdom of Prussia and its German allies. Italy was also allied with Prussia. Italian troops attacked Austria and took control of the province of Venetia.

After some initial setbacks, the Prussian military quickly established its dominance on the battlefield. The result was a shift in power among the German states away from Austria and towards Prussia. The German Confederation was abolished and replaced by the North German Confederation. The latter excluded Austria and the South German states and was dominated by Prussia. Austria also ceded Schleswig, Holstein, Hanover, Hesse, Nassau and Frankfurt to Prussia.

Next, Bismarck turned his attention to the south with the aim of uniting the remaining German states under Prussia. To facilitate this, he engineered a war with France - the Franco-Prussian War of 1870. In 1870 a dispute had arisen between France and Germany over the succession to the Spanish throne. A German prince, a member of the Catholic wing of the Hohenzollern dynasty, had been offered the position.

French emperor Napoleon III, already concerned by the growth of German power and influence, feared encirclement between a rising Prussia and a German influenced Spain. He had objected to the German Prince Leopold, and had instructed his ambassador to Prussia to obtain a promise from King Wilhelm I that Prussia would never again support the nomination of a Hohenzollern prince to the Spanish throne.

Bismarck arranged for the release of a transcript of the conversation between King Wilhelm I of Prussia and the French ambassador. Bismarck's carefully edited version, the "Ems Telegram," gave the impression that the two men had insulted each other and caused an uproar in both Paris and Berlin.

Napoleon III, pressured by the French press and public opinion, seized upon the telegram as an insult to the French ambassador and his government, and promptly declared war. Forced to choose between France and Prussia, the south German states rallied to Prussia. German military forces proved superior in the field. A series of swift Prussian victories in eastern France culminated in the Battle of Sedan on September 1, during which a large portion of the 120,000 strong French Army of Chalons, along with the French Emperor Napoleon III, were captured.

Fighting continued for some five more months, culminating in the siege and subsequent fall of Paris on January 28, 1871. The armistice that ended the Franco-Prussian war was negotiated in a railroad car located at German military headquarters in Compiegne. The symbolism of that event would be repeated in two successive world wars.

Hostilities were formally brought to a close with the Treaty of Frankfurt on May 10, 1871. France agreed to pay reparations of five billion francs, gave Germany the city of Strasbourg and the fortifications of Metz, and relinquished control of the province of Alsace and the northern portion of Lorraine, Moselle. Alsace was home to a majority of ethnic Germans and had been part of the Holy Roman Empire until seized by Louis XIV.

Lorraine however was predominantly French. For Germany it was simply taking back a region that was historically a rightful part of the German-speaking world. For the French, "to the injury of Alsace was added the insult of Lorraine." The "lost provinces" of Alsace-Lorraine became a source of resentment that would poison French-German relations for the next three-quarters of a century, and it would become one of the contributing factors leading to World War I.

Significantly,Bismarck had opposed the annexations, fearing both the influx of Catholics into the German empire and the risks of making France into a permanent enemy, but had finally conceded the point in the face of overwhelming popular support for their seizure.

With the South German States now solidly in Prussia's orbit, Bismarck, on January 18, 1871 at the Palace of Versailles just outside Paris, had orchestrated the proclamation of the new German Empire, the Deutsches Kaiserreich. The Reich would be led by the now Emperor, Wilhelm Fredrick, with Berlin as its capital.

He had brought into being a new European superpower. The German Empire had the largest population of any European state, was the most industrialized, and boasted an economic output that would soon overtake even that of Great Britain. Having unified Germany, Bismarck now needed to ensure its stability. This he intended to do by building alliances with key European powers and forestalling the creation of any alliances that might conceivably threaten the German Empire.

The Bismarckian System and the Realignment of Europe

Bismarck is said to have once observed that, "German foreign and military policy was hostage to its geography." Lying astride the heart of Europe, the rise of German military power could simultaneously threaten virtually all of the nations of Europe. Bismarck's principal aim was to insure that the rise of Germany would not precipitate an anti-German alliance by its neighbors. Above all else, he wanted to insure that Germany would not find itself in a position where it would have to fight a war on two fronts concurrently.

The Bismarckian international system that he implemented had three principal objectives: maintain friendly relations with Great Britain to insure continued British neutrality, isolate France, and seek an alliance with the conservative monarchies of Austria-Hungary and Russia.

While aware of the danger of French ambitions to retake Alsace and Lorraine, Bismarck realized that France alone could not stand up to German military power. The possibility of any kind of French-British alliance, while possible, seemed remote. Britain was continuing to pursue a policy of non-involvement in European politics. Moreover, France, its historic enemy, remained a potent rival in the race to colonize Asia and Africa.

In 1873, Bismarck turned his attention to Russia and the vanquished Austria, creating the "League of the Three Emperors." The League was designed to bring the conservative monarchies of Austria-Hungary, under Emperor Franz Joseph I, and Russia, under Tsar Alexander II, into alignment with Prussia.

Each party was obliged to come to the others' aid in time of war. In this way, Bismarck intended to maintain the balance of power within Europe and insure that no anti-German alliance would be formed. The Three Emperors League had an inherent weakness, however. Austrian and Russian interests were increasingly at odds in the Balkans.

The steady weakening of Turkish control over the Balkans had inspired a succession of revolts among the various subject peoples there. Austria-Hungary, whose heterogeneous population included many ethnic elements also present in the Balkans, found the prospect of a score of independent countries in the Balkans based on ethnicity profoundly destabilizing to its empire.

Russia, styling itself as the protector of Slavic people everywhere, used that pretext in advancing its own geostrategic interests in the Balkans. Among those interests was securing warm water ports on the Mediterranean as well as the ability to outflank Turkish control of the Dardanelles.

Ultimately, Germany would have to choose between an alliance with Austria-Hungary or an alliance with Russia. Wilhelm Fredrick I and Alexander II had both favored a German-Russian alliance. This was not without precedence. A similar alliance had existed between Catherine II (the Great) of Russia and Fredrick II of Prussia. Their mutual animosities notwithstanding, the two had signed a defensive alliance in 1764, and had collaborated in the successive partitions of the Polish-Lithuanian commonwealth that began in 1772.

A similar alliance would be made between Adolph Hitler and Joseph Stalin in 1939. Bismarck, however, was determined to unite the German-speaking people under Prussian leadership, and insisted on Austria-Hungary as Germany's main alliance partner. He threatened to step down as Chancellor if he did not get his way.

There was nothing inevitable about the alliance structure that would ultimately coalesce in the closing years of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth century. A German-Russian alliance had always been a distinct possibility. Indeed were it not for Bismarck's opposition, it might well have come about. Such an alliance would have left Austria and France as the two "isolated" parties.

Having both been victims of Prussian aggression, the two countries would have been natural allies. Moreover, their foreign policies were highly compatible. France had little interest in the Balkans and Austria-Hungary had little interest in overseas colonies. A Russian-German versus an Austrian-French alignment would have left Italy surrounded by two historic enemies and put it firmly in the German-Russian camp.

Such an alignment would not only have been plausible but it would also have been more consistent with historical precedent. We can only speculate how an alternative alliance structure would have affected subsequent British and Ottoman policy.

Angered by what it perceived as a lack of German diplomatic support for its gains from the Russo-Turkish War of 1777-78, Russia abandoned the pact in 1879. Bismarck tried again, creating a more formal, officially documented, Three Emperors Alliance. The alliance was concluded in 1881 for a term of three years and was renewed in 1884, but it lapsed in 1887. Bismarck then proposed a "reinsurance treaty" with Russia under which Germany and Russia both agreed to observe neutrality should either party be involved in a war with a third country.

The fact that Russia and Germany had moved from mutually supporting each other in the event that one of them found itself at war to being neutral underscores the steady divergence in Russian-German relations over this period. This neutrality would be applicable if Germany attacked France or Russia attacked Austria. In a secret protocol, Germany also pledged to remain neutral in the event of a Russian intervention in the Bosporus and the Dardanelles.

The three-year treaty remained in force till 1890. The Russians asked for a renewal, but by then Bismarck had been dismissed and his successor, Leo von Caprivi, was unsupportive. Moreover, the German Foreign Office had concluded that the Reinsurance Treaty with Russia was incompatible with the aims of the Dual Alliance between Germany and Austria.

In 1881, Italy joined the Dual Alliance to create a Triple Alliance under the terms of which Germany and Austria-Hungary would assist Italy if France attacked it. In fact, this alliance proved to be meaningless, for Italy went on to negotiate a secret treaty with the French under which it would remain neutral in the event of a German attack on France - a possibility that became reality in 1914.

Bismarck's insistence in making Austria rather than Russia the keystone of Germany's alliance system would prove to have enormous consequences on the alliance structure that would eventually emerge at the beginning of the twentieth century. As Russian-Austrian rivalry in the Balkans increased, Germany found itself increasingly in the position of supporting Austria at the expense of its relationship with Russia. In turn, Russia found itself increasingly isolated diplomatically within Europe. The strands of the carefully knitted Bismarckian system were beginning to loosen. In the next few years they would completely unravel.

In 1890, Bismarck found his historic career at an end. The new German Kaiser, Wilhelm II, unceremoniously replaced him. The satirical British magazine Punch lampooned the move as "dropping the pilot." The new Kaiser now declared that he would protect "Germany's place in the sun" by following a more vigorous and rapid expansion of the German empire.

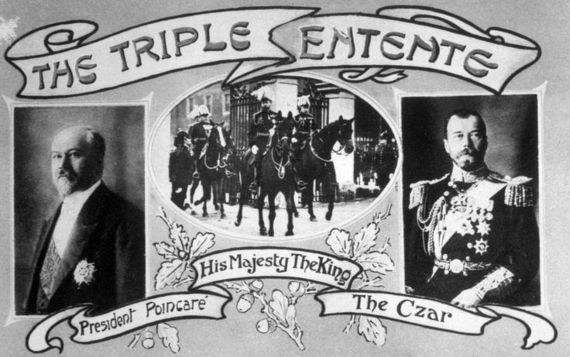

The Formation of the Triple Entente

Even though Bismarck had insisted on an alliance with Austria, he had repeatedly sought a diplomatic accommodation with Russia to forestall any kind of French-Russian alliance. Such an alliance seemed a remote possibility. Republican, revolutionary France seemed to have little in common with conservative, backward Russia. But driven by what they both perceived as an increasingly belligerent Germany, the two countries increasingly found common ground. The rapprochement was rapid.

In 1891, barely a year after the collapse of the Russian-German reinsurance treaty, a contingent of the French Naval fleet visited the Russian naval base at Kronstadt and was warmly welcomed by Tsar Alexander II. On their arrival they were greeted by a performance of the French national anthem La Marseilles. The visit marked the first time that the French anthem had been performed in a public setting in Russia. Prior to that visit any such performance would have been a criminal offense. Two years later, the Russian Fleet reciprocated with a visit to the French naval base in Toulon.

The two countries agreed on a military convention in August 1892, signed by the Chiefs of the respective Army General Staffs, pledging that if either was attacked by Germany, or by one of Germany's allies supported by Germany, the other would immediately attack Germany. The agreement further stipulated that in the event of war France was obligated to mobilize at least 1.3 million troops and Russia 700,000 to 800,000. After extensive negotiations, this Franco-Russian alliance was formally accepted in both countries on January 4, 1894. In October 1896, Nicholas II paid a visit to France. It was followed by a visit of the French President Faure to Saint Petersburg in August 1897.

The new French-Russian alliance had some unexpected consequences. With the encouragement of the French Government, Russia issued a large number of bonds, via the Paris Bourse. The proceeds were used to develop its railroads and transportation infrastructure and modernize the Russian military. Anything that would allow a more rapid mobilization of the Russian military, from railroads to streetcars, was seen to be in France's strategic interest.

These are the "Russian Bonds" that Lenin repudiated after the Bolshevik revolution; claiming that interest and principle had long since been paid with the Russian blood spilled for France on the Eastern Front. Many of these bonds, still unredeemed, continue to circulate today and remain at the root of countless financial scams. The new alliance made all things Russian the height of fashion in Paris. From the Ballet Russe to vodka and caviar, Russian culture was greeted with open arms by Russia's new French allies.

In 1898, Germany enacted the first, of what would eventually be four, Fleet Acts as part of a deliberate policy of challenging British naval supremacy. The German action came at a time when Britain, as a consequence of international disapproval of its actions in the Boer war, was finding itself increasingly isolated in the international community. The challenge also came at a time when London was acutely aware of a sense of imperial over reach. Great Britain remained a powerful country capable of meeting the challenge of any of its adversaries, but increasingly it was clear that it would be hard pressed to meet the challenge of multiple adversaries simultaneously.

Faced with a direct threat to its naval supremacy, the Admiralty developed and launched the dreadnought class of battleships. Named after the first ship launched, the dreadnought design offered two revolutionary innovations: an "all big gun" armament configuration with an unprecedented number of heavy caliber guns and a steam turbine propulsion system. Subsequent innovation saw the power plant converted from coal to fuel oil, increasing both speed and cruising range. These super battleships, by the standards of the early twentieth century, instantly made all previous pre-dreadnought battle ships obsolete, towering over them in both speed and fire power.

Faced with what it perceived as a direct and growing threat from Germany, Great Britain slowly abandoned its historical neutrality towards Europe in general and Germany in particular and, in turn, began to look for allies with which to contain German ambitions while at the same time reducing its imperial burdens. The search brought an unlikely set of allies, from an accommodation with the United States to an alliance with Italy in the Mediterranean and Japan in East Asia. Two additional allies, in particular, would, historically, have been highly unlikely ones.

France, driven by various French attempts to dominate the European continent, from Louis XIV to Napoleon, had been Great Britain's historic nemesis. Even after Waterloo, France remained a formidable competitor to Great Britain for power and influence around the world, and it had emerged as a strong rival in the race to colonize Africa and Asia.

As late as 1898, the two countries had almost gone to war over the Fashoda incident in the Sudan; where France tried, unsuccessfully, to oust Great Britain from the upper Nile. But now, British attitudes towards its historic rival began to change. In 1904, London and Paris signed a series of agreements called the Entente Cordials. The agreements marked the formal end of Britain policy of neutrality in European affairs. Their importance was underscored by a series of visits to Paris by King George V.

These negotiations served to forge a political alliance in response to the growing strength and influence of Germany. Although the entente did not include any specific clauses for mutual defense, privately the British government had assured Paris that, in the event of war with Germany, Great Britain would support France militarily.

There was still one more unlikely ally to join the alliance. For decades Russia and Great Britain had engaged in "The Great Game" for power and influence across central and East Asia. Russia's steady expansion to the east had often brought it into conflict with British interests in Persia and the Indian subcontinent. Even in China, Russia's ambitions in Manchuria and western China, although geographically removed from British interests in Hong Kong and south China, were still a cause for concern.

By 1907, however, the tensions and rivalries of "The Great Game" had been set aside for a newer and more acute concern, containing German ambitions. That year, Great Britain and Russia signed the Anglo-Russian convention. In less than a decade, Britain had reconciled with its historical nemesis France and with its great power rival in central Asia, Russia, to form the Triple Entente.

Bismarck's carefully constructed foreign policy was in ruins. One by one, the core principles of the Bismarckian system had collapsed: Britain had abandoned its historic neutrality to join an anti-German alliance, France had ended its isolation by reconciling with its historic nemesis Great Britain and had successfully forged a military alliance with Russia, and Germany now faced the one scenario that Bismarck had worked so tirelessly to avoid; powerful enemies joined together in mutual support on both its eastern and western borders.