1916 The Caucasus: The Trabzon Campaign

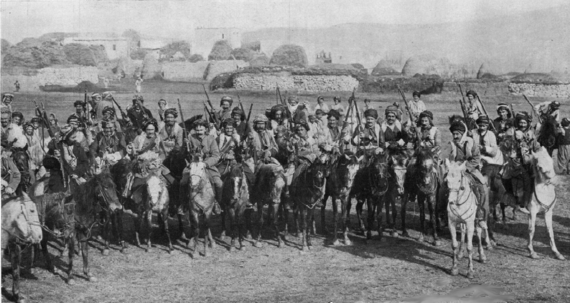

Russian troops before the Battle of Erzurum, January 1916

The Caucasus campaign was, in terms of forces deployed, a relatively minor theatre of World War I. Its long-term strategic importance, however, far out weighed, its practical tactical value. The campaign was fought exclusively by Russian and Turkish forces and their associated proxies.

During the Gallipoli campaign the Caucasus theater was important in tying up large numbers of Turkish troops in the east. After Gallipoli, it represented a backdoor to Constantinople, although given the rugged terrain, mountain passes that were only crossable in the summer, and the lack of adequate roads, pressuring the Ottoman government by advancing from the east would have been an exceedingly difficult task.

The strategic importance of the Caucasus campaign was in the fact that eastern Anatolia represented a route into northern Mesopotamia and from there down to the Persian Gulf. In theory, the Russian campaign could be seen as the northern end of a two pronged pincer movement that would have crushed Ottoman troops in Mesopotamia between the Russian troops advancing from the north and British troops advancing from the south.

The strategic theory notwithstanding, there was little coordination between Russian and British forces. In fact, London saw Russian interest in northern Mesopotamia as problematic to British interests in the Persian Gulf and its developing oil fields. The British advance on Baghdad and into northern Mesopotamia was to a large degree prompted by London's desire to keep Russian troops out of the region.

In the end, Ottoman forces under Mustafa Kemal, the hero of Gallipoli, in eastern Anatolia were able to blunt the Russian drive to the southeast. The subsequent collapse of Russian forces following the Russian revolution gave Great Britain a free hand in Mesopotamia and in the subsequent organization of British controlled Iraq.

The Caucasus Campaign, 1916

In early January 1916, Russian forces launched a daring winter attack against the major Ottoman fort at Erzurum. Poor roads and harsh weather conditions generally meant that military operations were suspended during the winter. Taking the Ottomans by complete surprise, the Russian destroyed an entire Ottoman division at the Battle of Koprukoy between January 10 and 18. The following month the Russians broke through both of the defensive rings surrounding Erzurum and captured the city.

In April, General Nikolai Yudenich, Commander in Chief of the Russian Army in the Caucasus, divided his forces in two. One column moved north and captured the ancient port city of Trabzon (Trebizond) on the Black Sea. Control of Trabzon provided the Russians with a port to receive supplies and reinforcements for the Caucasus campaign. It also created the strategic option of landing a Russian force further west behind the Ottoman lines, although the Russians had no experience with amphibious landing operations and lacked the equipment to carry one out.

Enver Pasha, the Ottoman War Minister and Commander in Chief of Ottoman military forces, immediately ordered the Ottoman 3rd Army, under Vehip Pasha, to retake Trabzon. The offensive failed, and Yudenich counterattacked on July 2, striking at the communications center at Erzincan, south of Trabzon. At the battle of Erzincan, July 2 to 25, the Turkish 3rd Army was forced to retreat and Erzincan fell to the Russians.

The second column headed south towards the cities of Bitlis and Mus. Bitlis was heavily fortified. It was considered the last stronghold of the Ottoman Empire in southeastern Anatolia and was the gateway into both Mesopotamia and central Anatolia. Between March 2 and August 24, in a series of actions culminating with the Battle of Mus and the Battle of Bitlis, Russian forces overwhelmed the Turkish 2nd Army and pushed it back deep into Anatolia.

The fall of Bitlis and Mus opened the door for a possible Russian advance into northern Mesopotamia and a potential link up with British forces; trapping Ottoman forces there between the two Allied armies. It also meant that the oil fields around Mosul might come under Russian control. That possibility was one reason why the British government ordered British forces in Mesopotamia to renew their drive on Baghdad.

Russian advances in eastern Anatolia had prompted the Ottoman government to appoint Mustafa Kemal, the Turkish hero of Gallipoli, commander of the XVI Corps of the Turkish 2nd Army. Kemal, who would go on to become the first President of Turkey after the war, is credited with being the founder of the Republic of Turkey. In 1934 the Turkish Parliament bestowed to Kemal the honorary surname Ataturk -- Father of the Turks.

Kemal rallied his troops and counterattacked, retaking the cities of Bitlis and Mus, halting for the moment the Russian drive towards Mesopotamia. A further advance to recapture Van was stopped by the Russians at Gevas. By late September the Ottoman counterattacked had ended. With winter fast approaching both sides ended any substantive offensive operations.

By the end of 1916, Russian armies were in control of a broad slice of eastern Anatolia running from Trabzon on the Black Sea south toward Bitlis in the southeast corner of Anatolia. In addition to the considerable Russian force that now faced them, Ottoman forces were also facing an ongoing insurgency in their rear by Armenian irregulars. Considerable numbers of Armenian volunteers had also joined the Russian army in the Caucasus and were serving alongside Russian troops. By the end of the year Russian forces numbered approximately 250,000 men.