The Emergence of Anti-Submarine Warfare

World War I marked the emergence of submarine warfare, and its counter response, anti-submarine warfare, as a critical element of naval operations. Submarines were not a particularly new idea. The concept of an undersea boat had first been suggested by the Renaissance genius Leonardo da Vinci.

After the defeat of the Venetian fleet at the Battle of Zonchio in August 1499, he proposed to the Doge of Venice an undersea craft that could approach the Turkish galleys and drill holes in their hulls in order to sink them. He even designed the first primitive wet suit and a system of using air filled bladders to refloat the sunken warships. Da Vinci asked for half of whatever ransom was obtained by Venice for the return of any captured Ottoman officers and seamen. By 1515, he had designed a prototype submersible, although it does not appear it was ever actually built.

In 1578, the British mathematician William Bourne also designed plans for a submersible craft. It was not until 1620, however, that the first submarine was actually built. Cornelius van Drebbel, a Dutch inventor, built the first submersible by tightly wrapping a wooden rowboat in greased, waterproofed leather. The underwater ship had air tubes with floats to the surface to provide oxygen. It was powered by 12 oarsmen. The oars then went through leather gaskets in the hull. In its first trip in the Thames River, this first primitive submarine remained submerged for three hours.

The American inventor David Bushnell built the first submarine actually deployed militarily in 1776. Dubbed the Turtle, it was a one-man, wooden submarine powered by hand-turned propellers. During the American War of Independence it was deployed against British warships at anchor. The Turtle would approach the ships and attach explosives to their hulls. The explosives, however, failed to go off underwater and little came of the effort.

Robert Fulton, an American inventor living in France, designed and built a second submarine, the Nautilus, between 1793 and 1800. Jules Verne adopted the name for the submarine in his novel "20,000 Leagues Under the Sea." The submarine was roughly 21 feet long and six feet in the beam. It was built out of copper sheets affixed to a wooden frame. The craft looked remarkably modern, not unlike contemporary small research submarines.

The Nautilus carried a naval mine called a "carcass." The device consisted of a variously sized copper cylinder containing anywhere from 10 pounds to 200 pounds of gunpowder. The submarine would approach a ship, drive a spiked eye into its hull, and then speed away while simultaneously releasing the cable that passed through the eye and attached to the "carcass." When the mine came into contact with the ship's hull, a detonator, a gunlock mechanism, would set off an explosion.

The submarine could stay underwater for up to eight hours and proved to be remarkably effective, notwithstanding a tendency to leak. Fulton proposed to the French government that it build a fleet of submarines to counteract British naval power. Napoleon lost interest in the project, however, and nothing came of it. The British Admiralty was sufficiently alarmed by Fulton's proposal that they hired him to come to England and design submarines for the Royal Navy. After the British victory at Trafalgar, however, the project was abandoned.

Over the balance of the 19th century a number of countries experimented with primitive submarine designs. Both the Union and Confederate navies deployed submarines during the American Civil War. The Chilean Navy built a submarine during the Chincha Islands War. Other countries that developed submarines during this period included Peru, Ecuador, Great Britain, France, and Prussia. During this period the first torpedo design also began to emerge. None of these early submarines, however, proved to be particularly useful. Most sank while still being tested.

The modern era of submarine design began in the 1890s, when two rival American inventors, Simon Lake and John P. Holland, developed competing designs for the first true submarines. The U.S. Navy purchased Holland's design, while Russia and Japan opted for Lake's version. Their submarines used gasoline driven steam engines for surface cruising and electric motors for traveling submerged. Both inventors also invented the electric motor driven torpedo, ushering in the era of submarine warfare.

The first German submarine was designed by the Bavarian inventor and engineer Wilhelm Bauer, and was built by Schweffel and Howaldt in Kiel in 1850. It was intended to end the Danish naval blockade during the First Schleswig War (1848-1852). The submarine carried a three man crew and was designed to approach enemy ships while they were at anchor and attach explosives to their hulls. Named the Brandtaucher, "Fire-diver," it sank on its first test dive in Kiel harbor. It was rediscovered in 1887, raised in 1903, and placed in a museum.

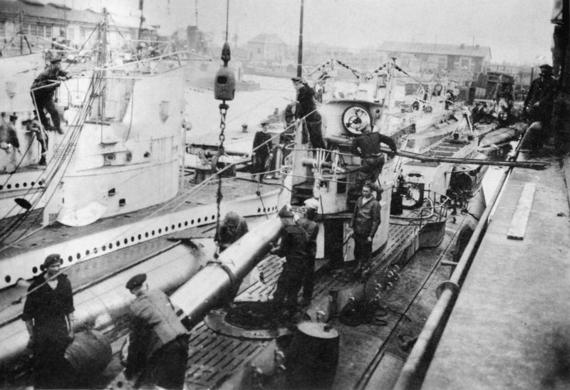

The modern era of German submarine construction began with the "Nordenfelt" design of submarines. These steam powered submarines were the result of a collaboration between a Swedish engineer, Thorsten Nordenfelt, and a British reverend, George Gannet. A number of submarines were built but they proved unstable. These were followed in 1906, by the Karp class, a double hulled, kerosene engine driven, single torpedo tube submarine.

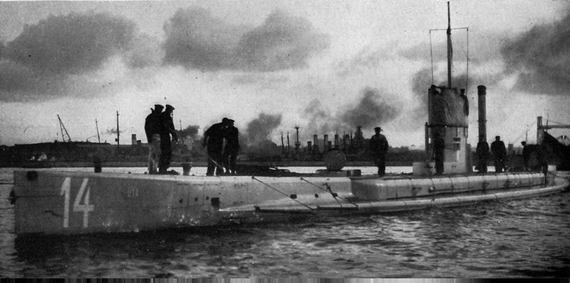

The SM class, the next evolution on German submarine design, was deployed in 1908, starting with the U-2. These boats were 50 percent bigger and had two torpedo tubes. Diesel engines were installed beginning with U-19. At the beginning of the war in August 1914, the Imperial German Navy had a total of 48 submarines across 13 different "classes," or designs, either built or under construction.

The German word for submarine is Unterseeboot, which was shortened to U-boat, and remains the German designation for submarines from World War I to the present day. The first ship sunk by a self-propelled torpedo fired from a U-boat was the HMS Pathfinder. It was sunk by SM U-21 on September 5, 1914.

Initially, the British Admiralty had dismissed the use of submarines as a threat to surface warships. The steady success of German submariners against Royal Navy ships, and the realization that German submarines could sink British battleships, caused a re-evaluation of the threat that they presented. The danger posed by U-boats was underscored when SM U-9 sank three British armored cruisers on the afternoon of September 22 1914.

At first, British anti-submarine countermeasures were largely ineffective. At the time there was no means of identifying submerged submarines much less attacking them. Most submarines that were destroyed had been on the surface and were attacked either by ramming or by surface fire. In a throwback to ancient naval tactics, a number of British warships designated for anti-submarine warfare were even outfitted with specially designed rams on their bow to sink German submarines.

A primitive form of depth charge had been developed in 1913, by taking a standard Mark II mine and fitting it with a hydrostatic pistol pre-set to detonate at 45 feet below the surface. Called a "dropping mine," it could be effective to 100 feet below the surface, well within the effective depth that WWI era submarines could reach. The device carried a charge of 1,150 pounds of explosive and the resulting explosion could pose a danger to the ship dropping it.

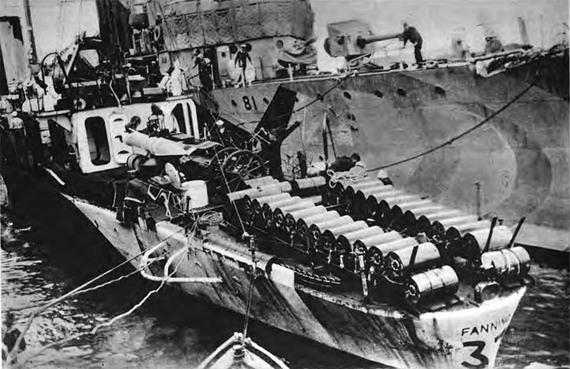

The first effective depth charges did not become available until January 1916, with the introduction of the Type D depth charge. These were the familiar barrel shaped design and carried a charge of either 300 pounds or 120 pounds of TNT. Slower ships used the smaller charge to ensure that the resulting explosion wouldn't damage them. For most of the war, however, demand for the depth charges exceeded the supply and most ships rarely carried more than two depth charges.

The first successful depth charge attack was against U-68 off Kerry, Ireland on March 22, 1916. Over the course of the war a total of 74,441 depth charges were issued by the Royal Navy, 16,451 of which were fired, resulting in 38 outright "kills," and aiding in the subsequent destruction of 140 more U-boats.

There were a variety of tactics employed in defending against U-boat attacks. The most effective tactic was turning toward the U-boat and attempting to ram it. If the boat submerged, the merchant ship's superior speed over a submerged U-boat would allow it to escape. Over half of all attacks against merchant ships by U-boats were defeated in this way.

World War I era torpedoes had a range of between 1,640 and 3,380 yards. The range eventually increased to 9,190 yards. Ranges were based on an average speed of 27 knots. At the top speed of 35 knots, the range, even on later models, would drop by 60 percent--to between 2,400 to 3,800 yards. German U-boats had a submerged speed of about seven to eight knots versus those of merchant vessels on the surface of between 11 and 13 knots. That meant that within 15 to 30 minutes a merchantman could open up a distance between itself and an attacking submarine to place it beyond torpedo range.

A second option was either arming merchant ships for self-defense, or arming and manning decoy ships with concealed deck guns. These were the so-called Q ships. If a U-boat surfaced, Q ships could engage and sink it. There were never enough Q ships to make a real difference, however, and U-boats rarely surfaced. The Germans argued that such tactics put merchant ships outside the protection of the Cruiser Rules. Since the Germans weren't abiding by those rules anyway, the point was largely academic. In total, sixteen U-boats were destroyed over the course of 1915, by these various tactics. In return the U-boats sank a total of 370 ships totaling 750,000 Gross Registeedr Tons (GRT).

In 1916, the Germans returned to a strategy of using U-boats to reduce the British Grand Fleet's numerical superiority. The plan was to stage a series of operations that would lure the British Fleet into an ambush, a killing zone, where prepositioned U-boats could open fire without warning as the fleet approached.

Since the U-boats could not keep up with the faster battleships, they would have to be prepositioned in patrol lines while the German Fleet acted as bait to draw the British Fleet into the trap. A number of these operations were staged in March and April of 1916 with no success. They were repeated in August and October, again with no success. It is likely that the British Admiralty's knowledge of German Naval codes gave it ample warning of the proposed ambushes.

Ironically, no U-boats were present at the one fleet action that did take place--the Battle of Jutland. Since the fleet engagement had occurred largely by chance, there was not enough time to preposition U-boats in the area, nor were there any U-boats in the vicinity when the battle occurred.

The submarine came into its own as a naval weapon during the First World War. Over the course of the war German U-boats sank around 5,000 ships with a combined capacity of about 13 million GRT at a cost of losing 178 submarines and 5,000 men in combat. Had Germany been able to deploy sufficient numbers, submarines might well have changed the outcome of the war. Since then, along with surface ships and naval air forces, the submarine has become a critical element of the triad that constitutes naval power in the modern world.