Germany and the Irish Easter Rebellion

During the First World War Germany and its allies adopted a strategy of fomenting rebellion in many of Great Britain's far-flung colonies as a way of weakening Britain's military capabilities. Enver Pasha, the Ottoman Minister for War, focused on inciting rebellion among the Muslim subjects of the British Empire. Berlin, on the other hand, tried to use Irish and Indian nationalists in a similar way.

Germany also attempted to use a variation of this strategy to try to incite a war between Mexico and the United States, as well as to recruit German-Americans to fight on Germany's behalf. That gambit would backfire disastrously when its disclosure in the Zimmerman telegram paved the way for the American intervention into World War I on behalf of the Allies.

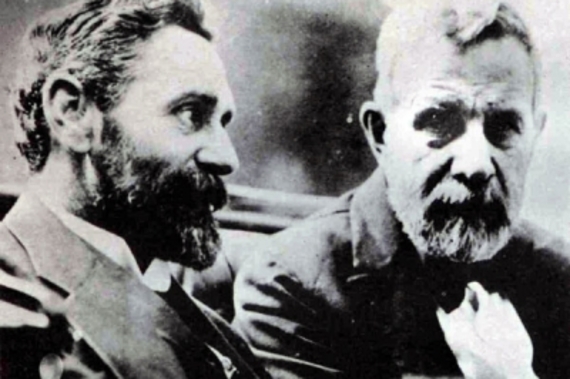

Within days of the start of World War I, Irish nationalists reached out to Germany for support in their struggle for Irish Independence. In early August of 1914, Sir Roger Casement, a former British diplomat of Irish extraction, and John Devoy, the head of the nationalist Clan na Gael, met in New York with Germany's Ambassador to the United States, Count Johann Heinrich von Bernstorff. At the meeting the Irish nationalists proposed to organize an Irish revolt against Great Britain if Germany would sell guns to the Irish revolutionaries and provide officers to organize and train an Irish military force.

On September 13, 1914, in Washington DC, Casement met with Franz von Papen, the German military attaché, to again seek Germany's support. At that meeting, Casement suggested that an Irish Brigade be organized from among the Irish prisoners of war from the British Army that had been captured by the Central Powers. The Brigade, he proposed, would fight alongside German troops against Great Britain and the Allies.

A month later, in October 1914, Casement, styling himself an Ambassador of the Irish nation, traveled to Germany, via Norway, to meet with officials in the German government. On December 27, 1914, in Berlin, Casement signed an agreement with German Secretary of State Arthur Zimmermann formally authorizing the creation of the Irish Brigade. The German government subsequently issued a declaration supporting Irish independence and hinting they might land an army in Ireland, someday, to advance the cause of Irish sovereignty.

The Brigade would be trained by the Germans and were to receive their own uniforms. Eventually, they would be made available to return to Ireland to fight against the British there. An Irish Brigade was in fact ultimately organized. Only 56 Irish POWs, out of the approximately 2,000 then being held in Germany, volunteered, however--far less than the usual 3,000-man strength of a brigade sized force. The men were sent to a POW camp in Limburg for training and eventually attached to the 203rd Brandenburg Regiment.

By the time of the Easter Rebellion in April 1916, however, the Irish Brigade had been dissolved. There is some evidence that Casement also had some involvement in a similar effort to recruit and organize an Indian brigade from among Hindu POWs held by the Germans. Dubbed the Hindu-German conspiracy, it sought German assistance to win Indian independence.

With the ongoing Battle of Verdun in full swing and Britain preparing for a new offensive on the Somme, Irish nationalists decided to organize a rebellion against British rule. Roger Casement traveled to Berlin to once again try to obtain German support for the planned uprising. He asked for 40,000 rifles to arm the Irish nationalists, as well as German officers to train them. He also sought to obtain a promise of a German landing on Ireland's west coast to support the rebels.

The Germans did subsequently offer 20,000 Russian 1891M Mosin-Nagant rifles. The rifles were standard equipment for the Russian infantry, and had been captured by German forces on the Eastern Front. Berlin, however, declined to send officers to train the Irish nationalists or to land German troops in Ireland. Germany also offered ten machine guns, as well as ammunition.

British code breakers had intercepted German communications from Washington DC discussing the shipment and were aware of its impending arrival. The ship transporting the weapons was a German merchant ship disguised as a Norwegian freighter, and was intercepted by the HMS Bluebell, an Acacia Class Sloop in the Royal Navy, on Friday, April 21 (Good Friday). While being escorted to Queenstown (today's Cobh) in County Cork, its Captain, Karl Spindler, scuttled the German freighter.

Disillusioned by the failure of Berlin to deliver the promised support, Casement ended his discussions and returned to Ireland by German submarine ostensibly to call off the rebellion. Historians have since hotly debated the issue of how much Roger Casement knew of the proposed rebellion. Some have claimed that Casement was only dimly aware of the proposed uprising and that his journey to Berlin to seek German aid was a precondition to the rebellion going forward.

Others have argued that the date for the rebellion had already been set in anticipation of the promised German support and that Casement was aware of the proposed date and his hasty return to Ireland was prompted by his desire to call off the uprising when the promised German support failed to materialize. Casement arrived in Ireland in the early hours of April 21, and was captured later that day. Charged with treason, sabotage and espionage, he was imprisoned in the Tower of London awaiting trial. He was subsequently found guilty and hanged at Pentonville Prison in London on August 3, 1916.

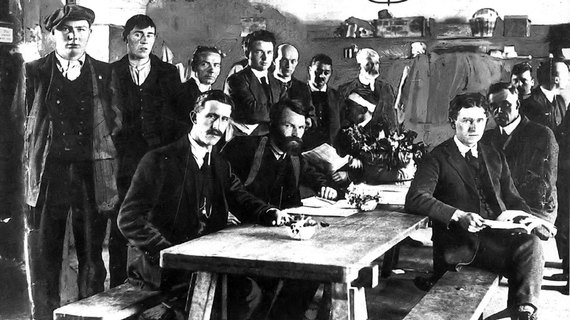

The British government was well aware of Casement's attempts to seek German support for a planned Irish rebellion. The British garrison in Dublin, however, believed it had Irish nationalism in check. To the surprise of both the British, and many Irish nationalists, rebellion erupted on April 24--Easter Monday--1916. Organized by members of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, and with the support of several other republican groups, approximately 1,250 rebels seized public buildings in the center of Dublin, including the General Post Office. Irish nationalists in Dublin quickly proclaimed a Free Irish Republic.

London was infuriated over the rebellion at such a critical time in the war, and particularly since Ireland had been promised home rule once the conflict was over. The rebellion lasted six days before it was extinguished. More than 300 Irish nationalists had been slain and over 100 British troops killed. Initially there was resentment in Dublin against the rebels due to the damage caused and the civilian casualties caught in the crossfire. This changed, however, with the ensuing court-martials.

Popular belief, which was untrue, was that Sinn Fein, a separatist organization that was at the time neither militant nor republican, was behind the uprising. Sixteen of the rebels were executed. The most prominent leader to escape execution was Éamon de Valera, commandant of the rebel's 3rd Battalion and a future president of Ireland. He was saved, in part, because of his American birth. Over 1,400 of the rebels were shipped across the Irish Sea and interned in England and Wales.

Casement's remains were eventually repatriated, after numerous requests, to the Irish Republic in 1965. His body laid in state at Arbour Hill for five days. Approximately half a million people filed past his coffin. He received a state funeral attended by over 30,000 people and was buried with full military honors. Among those present was the 81 year old Eamon de Valera, President of the Republic and the last surviving leader of the Irish rebellion. He attended the funeral despite his doctor's orders not to.