La Carte d'après Nature, an exhibition curated by Thomas Demand, will be on view at the Matthew Marks Gallery, 522 West 22nd Street (between 10th and 11th Avenues) through October 8, 2011. Gallery hours are Tuesday through Saturday, 11:00 A.M. to 6:00 P.M.

Since the Surrealists of the 1920s and 1930s undertook to make an art of the unconscious that freed the artist and viewer from the authoritarian constraints of overzealous rationalism and morality, every successive generation of artists has learned some new lesson derived from the Surrealist project of articulating the free exchange of form in Nature and its representations in the Mind.

German artist Thomas Demand continues the artistic fixation with the Surrealist equation of Mind and Nature, but unlike preceding generations, he doesn't center his exploration on the nihilistic convulsions and injuries inflicted on civilization through its divorce from nature. Instead, Demand has chosen to highlight the synergism and synchronicity discernible between the forms produced in the Mind and the forms produced by Nature in his exhibition La Carte d'après Nature, which he curated originally for the Nouveau Musée National de Monaco and since this July has been installed at the Matthew Marks Gallery in New York. This synergism and synchronicity is underscored by Demand in paring down the surrealist vision to fit what he calls "domesticated nature... potted plants, gardens, theme parks and models of wild growth."

It's a kind of demure surrealism we're not accustomed to seeing, yet the kind for all its subtlety is welcome today as a respite from the barrage of overblown surrealisms marketed in popular culture and found in such productions wanting irony as The Matrix films and Lady Gaga music videos. Demand's exploration is so subtle it can easily be mistaken as quite traditional, even academic, artmaking. All the more reason that it lends itself to comparisons with the cultivated theories of Mind and Nature we've inherited from the Renaissance, Enlightenment, Romanticism and Modernism.

It was as a result of the radically new domestication of civilization and nature that took hold of Europe some four to five centuries ago -- first by the aristocracy and later by the affluent middle classes -- that theories of the relationship between Mind and Nature began to be elaborated. In having the newfound freedom, leisure and resources to surround oneself with a domesticated nature, reflective minds became enflamed with ideas about Nature and the Mind. Suddenly contours, colors, patterns, markings, textures, durations, intervals, functions and processes found in nature became more readiy appreciable as a result of the labor and expense required in taming a simple garden. Reinforced with the paintings of the new landscape artists, such observations encouraged philosophers to infer the existence of some form of continuity or exchange between Nature and the Mind. Competing theoretical schools devoted to the study of the Mind, Nature and their relations developed. Some went so far as to divide Mind and Nature into a dualism of essence and experience, then debated whether forms, patterns and processes exist "all in the Mind" or "all in Nature."

Although the Surrealists were varied in their approaches to both Mind and Nature, it can be said that many of them made art that not only suggests Nature and the Mind aren't dualistic, but together form a single continuum which can't be separated. In this respect, Demand's selection of art for his exhibition seems to be redefining "the uncanny," or at least the domesticated uncanny, as being no more than our recognition of the moment when the Mind, in its attempt to impose a human-centered order onto Nature, finds that that order is already there. But does our recognition of that order in Nature mean that the Mind stands apart from Nature any more than, say, a groundhog responding to sight of its own shadow?

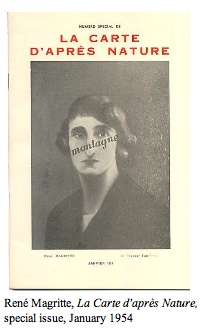

The very idea of a surrealist recognition seems to depend on the continuum of Mind and Nature, as we can only understand that of which we are a part. For that matter, Surrealist art implies that in forming one continuum, Nature and the Mind actually inform (that is, shape) one another simultaneously in the human experience of the world and the self. Demand alludes to this continuum when he announces in his press release that the title of his show, La Carte d'après Nature (The Map After Nature) is taken from the title of the journal published by René Magritte between 1951 and 1965, in which the artist "collected ideas from different times and places, relating them to one another by way of shared threads of thought."

I, for one, am grateful for Demand's perusal of shared threads from vintage art. After decades of being subjected to artists fixated on the nihilistic fractures and breakdowns of civilization to be "corrected" by the artistic operations of isolation, irony, recontextualization, and deconstruction, Demand's mannerist yet contained foray into vintage surrealisms is a refreshing breeze reminding us of what today's sustainability-minded ecophiles can learn from generations past.

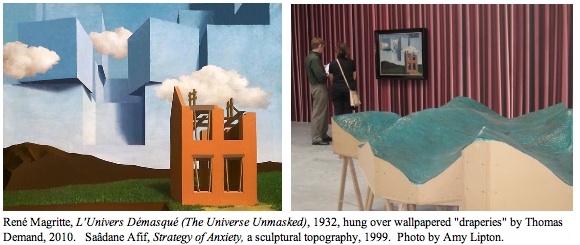

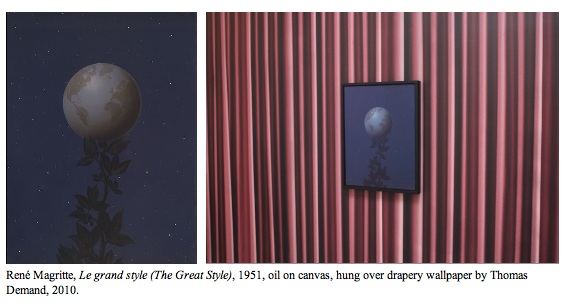

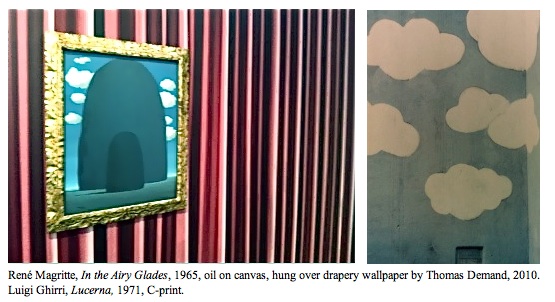

If Magritte's forays into the Mind-Nature continuum is only hinted at in the show's title, Demand's conspicuous hanging of three little-known paintings by Magritte confirms that this most ironic of Surrealists presides over the exhibition. Each of the paintings is strategically positioned on a wall "draped" with wallpaper digitally produced by Demand in the fashion of draperies covering a living room bay window and with which we close ourselves off from the world outside our control. But they equally suggest theatrical curtains that close off the portal of a proscenium stage from its anticipating audience.

The obvious reference to the boundary between the expectant audience and the actors (or in this case the visual artists) assembled onstage metaphorically summons to mind the mythical interface separating the Mind from the Theater of the World. But if Demand's curtain metaphor is at all functional in this age of ecological activism that renders Mind, Nature and the World as a continuum, it's because the curtain of the proscenium is designed to rise to impart sight of the world in which we find ourselves immersed.

Because the Magritte paintings embody the original Surrealism that opened the eyes of artists and audiences to the Mind-Nature continuum nearly a century ago, we are at first struck by the audacity of Demand placing the work by this most revered of modernists atop his own simulated curtains. But after we gain sight of the numerous vintage works mixing with art made in the last decade, it becomes obvious that Demand's imposed conversation with the master Surrealist sets the tone for the coalescence of contemporary and retrospective themes rebounding off one another throughout the installation.

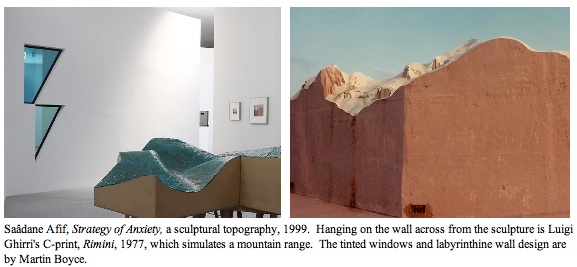

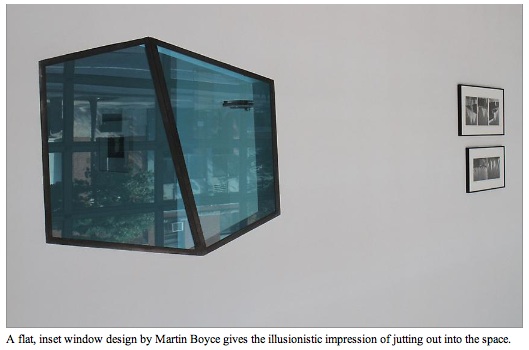

For that matter, so do the temporary and labyrinthine walls set at obtuse and acute angles in retro-expressionist fashion, replete with multilateral, chatrueuse- and cerulean-tinted windows that recall the modernist European aesthetics that are as much the protagonists in this discretely narrative space as the reciprocal themes of Mind and Nature.

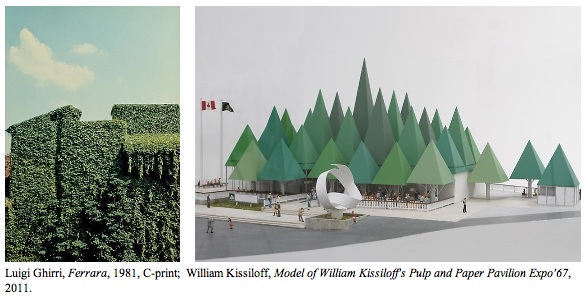

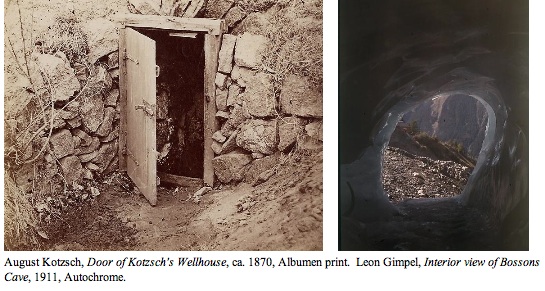

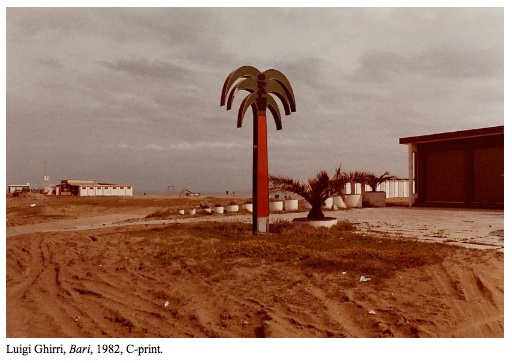

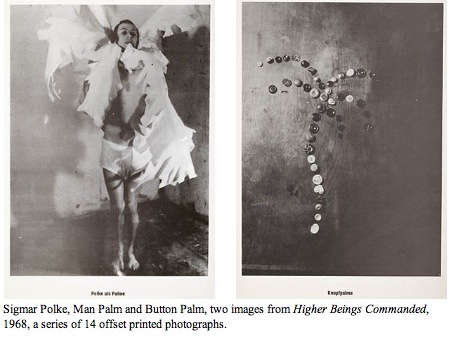

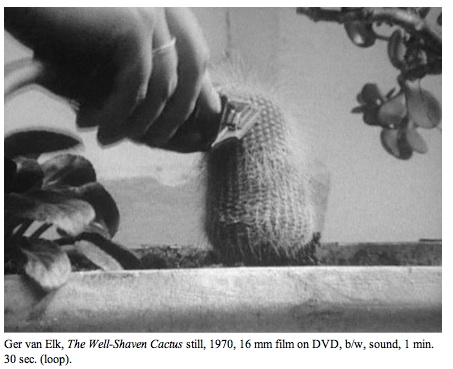

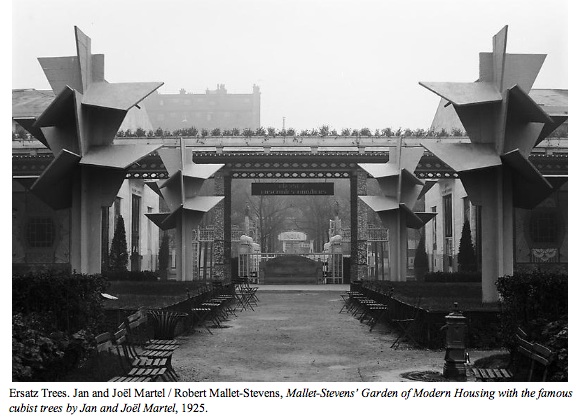

The vintage photography with which Demand confirms the historical paternity of the Mind-Nature continuum includes a selection of Albumen prints by August Kotzsch from the 1870s; an autochrome with light box by Leon Gimpel from 1911; a photo of cubist trees by Jan and Joel Martel in the 1920s; a range of photos by William Kissiloff, Ernst Roch, and Sigmar Polke from the 1960s; and especially a Ger van Elk video of a cactus being shaved, and a large and widely dispersed assembly of exquisite C-prints by Luigi Ghirri from the 1970s. As for the contemporary artists in the exhibit -- Martin Boyce, Henrik Hakansson, Tacita Dean, Saadane Afif, Rodney Graham, Chris Garafolo and Kudjoe Affutu -- all seem to echo the vintage work either by formal resemblance or thematic content. Demand further underscores the vintage aura of the show by screening 16mm films by Dean and Graham on obsolete projectors and playing music by Graham and birdsong by Hakansson recorded on old-fashioned vinyl records revolving on turntables.

In short, Demand has turned Magritte's journal devoted to "collected ideas from different times and places ... by way of shared threads of thought" into a space whereby the walls function as pages of a book bearing images and ideas attesting to the reciprocity of Mind and Nature -- the "prose of the world" one presumes would have enticed the aging Magritte himself.

It may be just my take on things, but Demand appears to have chosen the three Magritte paintings for their pictorial embodiment of three distinct models of the relationship of Mind to Nature and the world. If the painting Le grand style embodies the exterior-objective space of Nature, In the Airy Glades is easily the subjective interior of the mind. In between is The Universe Unmasked, the intersubjective space of architecture as the meeting place of inside and outside; room and landscape; dream and reality.

Considering that Magritte is the artist most famous for distinguishing between the mind's structural conflation of an object with it's function as a sign -- I mean, of course, Magritte's famous painting of a pipe with the words "Ceci n'est pas une pipe" ("This is not a pipe") -- the three paintings in this show remind us that Magritte had another side to him capable of blurring the hard distinctions between object, subject, sign and context to effect ambiguities that invite metaphysical speculation and mysticism, and visual puns that betray the unconscious conflations of the mind.

If I seem to be over-analyzing Demand's inclusion of Magritte, it's because an understanding of the work of Magritte in relationship to the recent developments underway in more mainstream art forms benefits from it. In Magritte's day the concepts I'm articulating here were confined to academic, intellectual and avant-garde enclaves. Today, although still not the grist of popular conversation, the most compelling artists in gaming, animation, and cinema are utilizing theories of ontology (what exists), epistemology (what is knowable), and phenomenology (what can be experienced) to facilitate the audience's (or in gaming, the player's) full mental and physical immersion.

For example, in mainstream cinema, some variation of these models of the Mind vs. Reality/Nature/the World permeate the work of Ridley Scott, James Cameron, Andy and Lana Wachowski, Darren Aronofsky, Kathryn Bigelow, Christopher Nolan, and David Fincher. Clearly the entry of such arcane theories of the mind and reality into popular culture indicates that the discussion of the Mind-Nature continuum is no longer merely academic, considering they inform the billion-dollar global industries of CGI as an artistic modeling tool as essential as any computer software or hardware.

It may even be said that the new mainstream media have rendered the age-old dichotomy of the subjective and objective as near-obsolete in the realms of art and entertainment, while rendering the intersubjective bridging of subjectivity and objectivity as among the most important new theoretical and psychological models of use to both scientists and artists today.

A major difference between the Nature and Mind relationship as portrayed in today's popular arts and the art of the Surrealists is that popular art assumes a mythical interface exists between the Mind and Nature. Of course, this interface is devised to effect a dramatic and entertaining narrative tension. In hugely popular films like The Matrix, Avatar and Inception, characters facing deadly cyber dangers in dreams or some other out-of-body projection wake up to find the dangers instantly vanish.

The Surrealists, on the other hand, sought to dissolve this mythical boundary. They held the events of dreaming to be as potentially perilous, if not more, than the events of waking life. Dreams have the capacity to disinter the repressed immoral and subversive desires of the unconscious psyche, enabling such desires to follow and overtake the dreamer even more threateningly when awake. It's ironic that the Surrealists here prove themselves to be more realistic than the media dreammakers of a popular culture obsessed with realistic portrayals.

By contrast, the artists assembled by Demand in La Carte d'après Nature show no sign of this imagined interface. Forms and ideas flow freely between Mind and Nature. In this respect, the exhibition is like a dream journal, that over an extensive span of time, relays the accumulating epiphany that has made the dreamer aware of a stage between dreaming and waking whereby s/he feels s/he is actively manipulating the form and content of the dream s/he is waking up from. Artists, who are experts at choosing and editing content and shaping media to conform to their wills, are particularly well attuned to this stage between waking and dreaming.

It is the artists' expertise at mapping the terrain between dreaming and waking -- the overlapping of Mind and Nature -- that compels Demand, like Magritte before him, to designate "the Map" ("La Carte") not just as a metaphor for art, but as the premier function of art.

Although La Carte d'après Nature concerns itself with the enclaves of a refined and fully awake, if sometimes punning, compilation of imagery and ideas, it no less conveys this sense of a world unfolding by intelligent design as one moves from work to work in the show, and especially when we survey whole rooms in succession. Which is to say that it is Demand's process of selection, editing, and arrangement of work that heightens the viewer's recognition of the forms and the spaces between forms, as well as the temporal processes and intervals between processes. It is Demand who sees to it that the forms and processes reciprocally mirror, mimic, rebound off, balance, invert, give way and conform to one another in ways that compel the alert viewer to imagine the boundaries of objects deliquescing into the fluid and protean plenum that informs the continuum of Mind and Nature.

If I've focused near-exclusively on Demand as if he were staging a solo show of his own work, that is because, despite the show's presentation as a group show, in summation it is more an authentic vision of Demand the artist. Demand might have more easily appropriated the art assembled in La Carte d'après Nature by copying it in the fashion that Sherrie Levine appropriates Walker Evans.

But make no mistake. In the control he wields over the work of the artists by way of the show's conceptualization, classification, mirroring and rebounding of themes, Demand has in effect gone one step further than Levine's process of copying by appropriating and redefining the authentic works of art, however temporarily. It's a choice that suggests Demand has theoretically reasserted the primacy of the aura of the original over the aura of the copy. (But then we might argue, with current auction records to support us, the aura of the original was never truly dimmed or surpassed in brightness.)

Then, too, in Surrealist art, as in dreams, the artist/dreamer commonly assumes or doubles the appearance and identity of others -- an act that affirms not just the continuum of Mind and Nature, but also the continuity of the human race. It is perfectly in keeping with the original Surrealists for Demand to blur the boundary between his own identity and art and the identities and art of the artists he includes in his show, both living and dead. In this context La Carte d'après Nature transcends the narcissism of artistic attribution by attaining a totality of vision that makes even the art produced a century before Demand's birth appear as if it were made for his 2011 installation.

Read other posts by G. Roger Denson on Huffington Post in the archive.