Here’s everything we know so far about Thomas Eric Duncan, the first patient to be diagnosed with Ebola in the United States. We traced his journey to the U.S. -- from his arrival in Dallas on Sept. 20, to his first signs of symptoms on Sept. 25, to the impact of his illness on the Dallas community since he's been hospitalized in critical condition.

1. He came to the United States to reunite with his son and marry his son's mother.

Duncan arrived in the U.S. on Sept. 20 to reunite with Louise Troh, a former romantic partner from Liberia, and son Karsiah Duncan after a 16-year separation, The New York Times reported. Duncan and Troh had met in a refugee camp in the early 1990s, but separated after Karsiah was born. Troh left for the U.S. in 1998, where she has lived since, according to The Times. Troh had previously visited Liberia to see him and plan his trip to the U.S., where they hoped to get married, The Star-Telegram reported.

“They made a plan for him to come to the States ... and plan a wedding,” said Troh's pastor George Mason to The Star-Telegram. “Every indication I have is that it was a long-standing plan and not related to his being infected.” Duncan was also looking forward to reuniting with his 19-year-old son, who attends Angelo State University in San Angelo, Texas, The Star-Telegram reported.

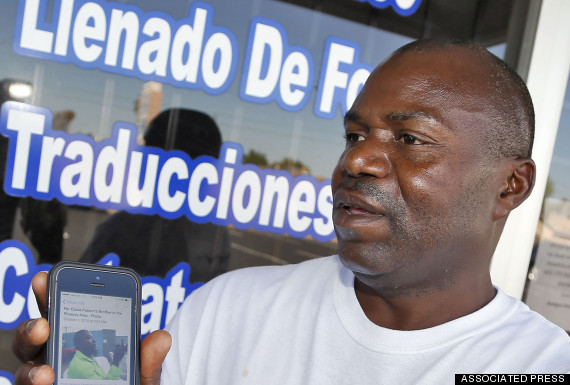

Wilfred Smallwood, who identified himself as a brother of Ebola patient Thomas Eric Duncan, speaks about his brother, while holding a photo of him, Wednesday, Oct. 1, 2014, in Phoenix. (AP Photo/Matt York)

2. He was screened before leaving Liberia.

Before getting on a plane to leave Liberia, health care workers at the airport took Duncan’s temperature and recorded it as 97.3 degrees Fahrenheit -- which means he did not have a fever before he took the long journey to Dallas. He had also filled out a survey asking if he had been exposed to anyone with the disease, to which he answered, “no,” according to the Associated Press.

3. He was exposed to Ebola days before his trip.

New York Times reporters have been able to pinpoint exactly when Duncan may have contracted Ebola. Just four days before his trip to the U.S., he had helped his neighbors transport Marthalene Williams, a sick pregnant woman, to and from a hospital. They were turned away from the hospital for lack of space, and Duncan had helped carry Williams from the car back to her house. She ended up dying early the next morning.

Mercy Kennedy, 9, cries as community activists approach her outside her home on 72nd SKD Boulevard in Monrovia, Liberia Thursday Oct. 2, 2014, a day after her mother was taken away by an ambulance to an Ebola ward. Neighbors wailed Thursday upon learning that Mercy's mother had died; she was among the cluster of cases that includes Thomas Eric Duncan, a Liberian man now hospitalized in Texas. (AP Photo/Jerome Delay)

4. He may not have known he was exposed.

Because Williams was the first Ebola case in Duncan’s neighborhood, it’s plausible that Duncan may not have known what he was getting himself into when he helped transport her to and from the hospital. Indeed, the Associated Press reported that everyone who had helped Williams get to and from the hospital assumed that her convulsions were related to her seven-month pregnancy. Those good Samaritans have since either been infected with Ebola or died.

What is known is that Duncan had told health workers he had just arrived from Liberia when he initially sought treatment at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital Dallas, his sister confirmed to the Associated Press.

Duncan’s family is defending him amid accusations that he knowingly got on a plane to the U.S. in order to seek care for Ebola. For one, they said, it takes a long time to obtain a visa to enter the U.S., which indicates that the trip could not have been a spur-of-the-moment decision in response to Ebola exposure. They also see Duncan as a hero for helping to care for Williams, who later died of Ebola.

"He’s a good man,” Duncan's half-brother Wilfred Smallwood told The Star-Telegram. “He attends church. He tried to save that woman’s life in Monrovia.”

5. His case is an important lesson for all U.S. hospitals.

His case exposed serious flaws in the emergency room intake process of a major hospital and alerted other medical centers across the country about the need to educate all staff about how to screen for Ebola. Both nurses and doctors who had initially assessed Duncan’s symptoms on Sept. 25 apparently had access to Duncan's travel history through the hospital electronic health record system, but they sent him home anyway with antibiotics -- a decision that may have potentially endangered his life and exposed scores of Dallas residents to Ebola symptoms.

But perhaps what’s more alarming is the way the hospital has released information about Duncan’s first contact with health care workers. In the very first press conference, a spokesman for Texas Health had nothing to say about Duncan’s gap in care or potential mistakes workers had made. Then the hospital admitted one nurse knew he had come from Liberia, but the information wasn’t properly disseminated. Then they said that a flaw in the workflow of the hospital's electronic health record system was to blame. Then it turned out both doctor and nurse did have access to his travel history, and that there was in fact no flaw with the hospital's record system.

“For me, the most disappointing thing isn’t that the system didn’t work, but in the aftermath, instead of helping every other hospital in the country understand where their system failed and learn from it, they have thrown out a whole lot of distractions,” said Dr. Ashish Jha, a professor at Harvard University’s School of Public Health, in an interview with The New York Times.

6. The family he came to visit is still at risk.

When Duncan was in Dallas, he stayed with his partner Louise Troh in her apartment, where she lived with three others: her 13-year old son, Duncan’s nephew Oliver Smallwood and a friend, Jeffrey Cole, The New York Times reported. Those four people were quarantined in the apartment -- along with the bedding and clothes that Duncan had used -- for six days before being moved to a more spacious home in an undisclosed part of the city. So far, they’re all asymptomatic, but have been under duress because of the quarantine, media spotlight and the stress of knowing they had come into contact with Duncan when he was infectious.

A member of the Cleaning Guys Haz Mat clean up company removes items from the apartment where Ebola patient Thomas Eric Duncan was staying on Oct. 6 in Dallas, Texas.(Photo by Joe Raedle/Getty Images)

7. Duncan may have exposed others to Ebola, too.

Duncan may have also exposed health care workers and community members to the disease, by the time he was transported to the hospital via ambulance on Sept. 28. The CDC is monitoring 10 people who had direct contact with Duncan while he was symptomatic -- three relatives and seven health care workers -- as well as about 38 other people who may also be at risk. So far, none are showing any symptoms of Ebola.

8. Duncan is currently fighting for his life.

Duncan is in critical condition and fighting for his life. Saturday (Oct. 4), he started receiving an experimental drug called brincidofovir. The drug has already been tested in up to 900 patients in late-stage FDA trials, but for viruses like cytomegalovirus and adenovirus.

A general view of Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital Dallas is seen where patient Thomas Eric Duncan is being treated for the Ebola virus.(Photo by Joe Raedle/Getty Images)

9. If Duncan survives, he could face charges in two countries.

Liberian authorities want to press charges against Duncan for allegedly lying on his airport screening questionnaire. Binyah Kesselly, chairman of the board of directors of the Liberia Airport Authority, told the Associated Press that Duncan had brought “stigma” to Liberian ex-pats for bringing the Ebola virus to the U.S. Texas authorities are also weighing whether or not to press charges against Duncan, but they’re not sure what those charges would be yet.