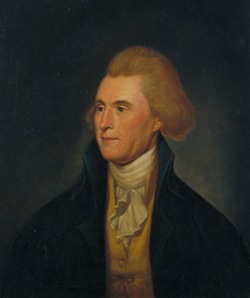

I recently appeared on the Today Show talking about Thomas Jefferson and making macaroni and cheese. Since it was so brief, I thought I'd share a few more fun facts about this early American foodie.

Thomas Jefferson served as minister to the court of Louis XVI from 1784 to 1789. Though no stranger to French cuisine when he set sail, the years spent in France completely revolutionized his culinary thinking and opened up a new gastronomic world for him.

We often view the eighteenth century in terms of elegance: Parisian salons, powdered wigs and rarefied manners. Jefferson's Paris was the years immediately preceding the Revolution, a time of extreme economic disparity. While royalty lived in excess, feasting on roasts and rich confections, Parisians were starving. Urban and rural riots - often caused by lack of affordable grain - were the order of the day. Intellectuals questioned the legitimacy of nobility and the monarchy itself and championed the rights of men to a free and prosperous life. It was the Age of the Enlightenment and Jefferson was a product of that thinking.

Though disgusted by the excess of Parisian society, Jefferson couldn't help but be drawn to its art, architecture, music, food and wine. A man of contradictions (he was adamantly against slavery yet never freed his 200 slaves), Jefferson socialized with the bourgeoisie and aristocracy, and was known to host lavish dinner parties in his Parisian apartment on the Champs Elysees (Bordeaux was his wine of choice). He employed four French chefs and had his slave, James Hemings, learn the art of French cooking. His favorite recipes were recorded in his own hand -- one of these recipes is of macaroni, then a term for pasta.

It was during his time in France that he came to understand the role and value of food in people's lives. He saw French food as a language that communicated his style and status yet he never supplanted his own American food traditions, only broadened them. He was a vocal defender of the New World and its natural products, and even grew corn in his Parisian garden!

Though he sided with the revolutionaries, Jefferson always looked at the Old World to make the New World better. When he sailed back to America in 1789, he brought back 86 crates of kitchen supplies including European cookbooks, the first pasta maker to enter the US, 680 bottles of wine, grapes vines (he said one day America would make wines as good as those in France), Parmesan cheese, olive oil, pasta, figs, apricots, teapots and tablecloths. In Virginia, these products blended with those arriving on slave ships from Africa, creating a unique Southern cuisine. In his Monticello kitchen garden, he grew Irish wheat, Italian grapes and French tarragon alongside Mexican chiles and African okra. Ironically, as much as he loved food he the only time he entered the kitchen was to wind the clock.

Cheers to this early American foodie and to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. Bon appétit!

Macaroni and Cheese

Thomas Jefferson served a variation of this modern recipe at a White House dinner in 1802, making this then exotic dish popular in America. His relative, Mary Randolph, includes a recipe for macaroni and cheese in the 1845 cookbook, The Virginia Housewife.

1 pound elbow pasta

1 bay leaf

salt to taste

4 tablespoons unsalted butter

4 tablespoons flour

4 ½ cups milk

1 ½ cups Gruyere, grated

3 cups cheddar cheese, grated

2 teaspoons Dijon mustard, preferably Maille brand (Jefferson's favorite)

pinch nutmeg

½ cup plain breadcrumbs

1 cup Parmesan cheese, finely grated

salt and pepper

1. Preheat oven to 350º F.

2. Bring a large pot of salted water to a boil and cook the pasta until not quite al dente, about 7 minutes. Drain, transfer to a bowl, and set aside.

3. Mix the Parmesan cheese and breadcrumbs in a small bowl and set aside.

4. In a saucepan heat the milk with the bay leaf, but don't boil it! Remove the bay leaf.

5. In a medium saucepan over medium heat, melt the butter and whisk in the flour until smooth. Whisk in the warm milk and cook, continuing to whisk often, until the sauce coats the back of a spoon, about 10 minutes.

6. Stir in the cheese, one cup at a time and whisk until the cheese is melted and incorporated. Whisk in the mustard, pinch of nutmeg, and season to taste with salt and pepper.

7. Remove pan from heat and stir in the reserved pasta. Pour into a baking dish and sprinkle the top with the Parmesan and breadcrumb mixture.

8. Bake until golden brown and bubbly, about 25 minutes. Let cool 10 minutes before serving.

Serves 6 to 8

Image:

Thomas Jefferson, 1791

Charles Willson Peale, American

Oil on canvas

Huntington Library, Art Collections and Botanical Gardens