Far too few psychiatrists, psychologists, and mental health professionals today have been exposed to the work of Dr. Thomas Szasz. Many have a stereotyped view of his ideas. Some don't even know who he was.

Do you recall The Myth of Mental Illness (1961), or Pain and Pleasure (1957), which preceded it? Or the more than 30 books that followed over five decades of radical, intellectual contribution (e.g., Law, Liberty and Psychiatry; Ceremonial Chemistry; The Manufacture of Madness; Suicide Prohibition; The Ethics of Psychoanalysis; and so many more with pithy and provocative titles).

Szasz died in 2012 at the age of 92. He was born in Budapest, Hungary, of Jewish, educated parents who fled to the U.S. when Hitler invaded Austria in 1938. They understood that Hungary was next in the Nazi's sights. Szasz was multilingual when he arrived in this country, speaking both French and German in addition to his native Hungarian, but he spoke not a word of English. That didn't impede his remarkable academic success in college and medical school -- though he could not get into a top ranked school or residency because of the Jewish quotas that prevailed.

He trained as a classic psychoanalyst in Chicago before serving in the Navy and then moving east to Syracuse, NY, where he made his permanent academic and personal home.

When I went to medical school and took my psychiatric residency at the State University of NY, Upstate Medical Center in Syracuse, Tom Szasz was already a legend. He was banned from teaching in the state psychiatric hospital affiliated with the medical school. But he still taught trainees and mentored many junior faculty because his brilliance was inescapable, as was the sharpness of his wit and the forcefulness of his challenges to a host of psychiatric conventions.

I recall my first seminar with him. I thought I would be willing to make a deal with the devil in exchange for being able to think as well as he did. In reading his work I saw that few people, in any field, could formulate and articulate concepts and arguments as keenly as did this lean, diminutive (in size) Eastern European who never lost his accent.

I also recall, some years later, my supervision sessions with him as he wore out my brain with staccato barrages of reason about how my profession was perpetrating intellectual fraud in claiming there was such a thing as mental illness and, worse, using that premise to involuntarily hospitalize people who had "problems in living." What was really hard was that I then would be on-call at the state hospital, often running there from his office to find the police waiting with a 250-pound agitated psychotic young man (or more than one). The local cops smiled and said "Hey doc, you're late. Here's your patient. We're outta here." If there is such a thing as mental whiplash, that was when I had it. I continued to be challenged by his ideas while having the gift of his collegiality for decades.

What Tom Szasz wrote and taught has informed and shaped my career, and many others. His influence often goes unrecognized. He was the ultimate libertarian, asserting that individuals needed to be protected from the power of the collective. As an immigrant Jew whose family escaped the Nazis he never forgot how ideas (ideology) can menace and destroy.

Szasz's intellectual tools were history, philosophical argument, ethics, logic, and humanism. He was a master at demonstrating how metaphor can take on the power of fact -- and be used in ways that erode liberty. Perhaps the best known of his metaphors is the "myth of mental illness," which incited early and enduring protests to the use of involuntary psychiatric treatment by patients and legal advocates, as well as many in my profession. That got him the mantle of being "anti-psychiatry" -- but he was not. He believed psychiatric practice should hold freedom over everything else, and that with liberty came personal responsibility. He believed that once mental disorders were proven brain diseases they would no longer be metaphors but belong to the field of neurology.

He conceived of therapy as a means by which experts, like psychiatrists, enabled patients to make the best use of their resources to have a rich and moral life. He also said that being a physician did not help with providing therapy -- and that doctors should forget they were doctors when treating psychiatric patients, and those who were not and aspired to act like MDs should let it go. His views against the use of psychiatric drugs were especially contrarian, and made appreciating his thinking all the more difficult.

Szasz's contributions to psychoanalysis are particularly forgotten. He was an early thinker in using concepts of relationships to supersede Freud's views of sex and aggression. His view of the psychology of schizophrenia (as deficits and distortions in the internal images that shape our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors) could help a lot of clinicians today.

Early in his work Szasz also modeled how doctor-patient relationships could mirror parent-infant, parent-child/adolescent, and adult-adult dyads. The goal of therapy was reaching the adult-adult stage to enable people to help themselves, free from the control of others, no matter how helpful they meant to be. These notions are at the heart of the mental health recovery movement today, and the shared decision-making that produces the best of outcomes for patients suffering from all chronic conditions.

Some of the last century's greatest psychiatrists frequently argued with him. They would claim he was wrong -- but brilliant. Not that I am one of them, but his emphasis on the individual was too dismissive of family and community for my work. What's more, we now have indisputable evidence of major mental illnesses having neurological (as well as genetic and molecular) pathologies -- unlike 50 years ago. And with that proof, neurologists still aren't rushing to fill the shoes of psychiatrists! I also have seen too many people take their lives in the throes of acute mental distress before treatment could avert their causing irrevocable damage to themselves and their loved ones.

But none of my differences with Tom Szasz diminishes my regard for this great man. His insistence on rigorously examining our ideas and his admonitions about the unintended consequences of would-be good intentions are timeless and priceless. His polemical style was a means of stirring -- rather than lulling -- the minds of psychiatrists and other mental health professionals.

I wrote this article after spending a sunny day in usually cloudy Syracuse, NY, with friends and colleagues gathered for a day-long symposium called a "A Celebration of the Life and Work of Thomas Szasz (August 8, 2014)." I hope he was listening in and hearing, in ways he would never permit when alive, the recognition (not just the argument) he continues to inspire.

---

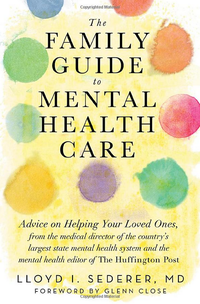

Dr. Sederer's new book for families who have a member with a mental illness is The Family Guide to Mental Health Care (Foreword by Glenn Close).

Dr. Sederer's new book for families who have a member with a mental illness is The Family Guide to Mental Health Care (Foreword by Glenn Close).

Dr. Sederer is a psychiatrist and public health physician. The views expressed here are entirely his own. He takes no support from any pharmaceutical or device company.

www.askdrlloyd.comhttp://www.askdrlloyd.com