Hearings held last week by the House Ways and Means and Senate Banking Committees marked a turning point in Congressional debate on China's currency manipulation policies. There was widespread support for getting tough with China from members of both houses, and only token opposition from a few business witnesses. Fred Bergsten, head of the Peterson Institute for International Economics, came out in favor of a limited form of the Ryan-Murphy currency bill (HR 2378), which would allow the Commerce Department to treat currency manipulation as a subsidy in some countervailing duty investigations. He also called on the Treasury to name China a currency manipulator, and for the United States to mobilize allies in the G-20 to file a complaint against China at the WTO, requesting authority to impose restrictions on Chinese imports unless its currency rises significantly.

Yesterday, Ways and Means Committee Chair Sandy Levin announced that the committee will meet on Friday, September 23 to mark up a version of the Ryan-Murphy currency legislation. Levin noted that he had received a letter signed by 101 House members, including 30 Republicans, urging the Committee to consider and pass the Ryan-Murphy bill.

Meanwhile, opponents of getting tough with China have been reduced to recycling widely discredited claims. In a recent posting on his blog, former Labor Secretary Robert Reich (who also helped found EPI and is currently a board member), claimed China might retaliate by selling off some of their $843 billion in Treasury bill holdings. We should be so lucky: the dollar would fall, making U.S. exports more competitive. And it would have no impact on U.S. interest rates (contrary to Reich's assertions). As Paul Krugman has pointed out, "this fear is completely misplaced: in a world awash in excess savings, we don't need China's money -- especially because the Federal Reserve could and should buy up any bonds the Chinese sell."

Some U.S. businesses could suffer in the unlikely event that the U.S. and China do enter into a trade war. Companies like Boeing that sell lots of aircraft to China and foreign investors in that country could be penalized. However, China's exports from the United States exceed U.S. exports to China by more than four-to-one. Exports make up approximately one third of China's GDP, while U.S. exports to China are less than 0.7% of U.S. GDP. Countries like China with large trade surpluses always have more to lose in a trade conflict. This also illustrates why it's important to persuade other major governments such as the European Union (E.U.), Brazil and India to join us in threatening China with sanctions for its illegal currency manipulation. If the U.S. and E.U. both impose tariffs on Chinese imports, China would be unable to play Boeing off against Airbus.

Reich also claims (as do many others) that revaluation would not create jobs in the U.S. because other lower wage countries would just take their place, and because other countries would rush in to compete in China and other markets. But this claim ignores many studies showing that if the dollar falls, relative to the yuan and other currencies, the U.S. trade balance will ultimately improve. The most recent study, by Bill Cline of the Peterson Institute, showed that for every 1 percentage point rise in China's real effective exchange rate, its global current account surplus (the broadest measure of its trade balance) will fall by $17 to $25 billion. The corresponding improvement in the U.S. current account would be $2.2 to $6.3 billion. Thus, a 25% appreciation in the yuan would reduce China's current account surplus by $425 to $580 billion, and reduce the U.S. trade deficit by $55 to $157.5 billion. Cline's conservative estimates imply that only one-eighth to one-quarter of any reduction in China's current account would be reflected as an improvement in the U.S. trade balance. Nonetheless his study shows the U.S. trade balance would improve significantly if Chinese currency manipulation were reduced or eliminated.

Reich's claim about substitutes from other low wage countries primarily relates to the effect of currency manipulation on U.S. imports. But currency manipulation also acts like a tax on U.S. exports. This reduces U.S. export to China and every country around the world where we compete with Chinese exports. According to data from the Federal Reserve China is our most important competitor in world export markets, more important even than the EU or Japan. Eliminating currency manipulation will stimulate U.S. exports to China and the rest of the world, creating new jobs in the United States, especially in manufacturing, which produces most traded goods.

It is also important to remember that China is not the only country that manipulates its currency--other countries also need to revalue. Cline and Williamson (2010) have also identified Singapore, Taiwan, Malaysia and Indonesia as currency manipulators, and other countries such as Japan, Sweden and Switzerland need to revalue as well. A global currency realignment along these lines would result in further improvements in the U.S. trade balance.

Reich also argues that China's export policy doubles as a social policy that is needed to absorb the millions of workers flooding into the cities from the countryside, and that China risks riots and other upheaval if they don't continue to manipulate their currency. This claim ignores the fact that revaluation would be good for China's workers in several ways. It would raise real wages, allowing them to purchase more imports and enjoy the fruits of their labors. It would put downward pressure on Chinese inflation. It would also force China to invest more in infrastructure and the social safety net. This would create the domestically-oriented growth needed to sustain China's development while providing its citizens with the public and social services (e.g., housing, transportation, safe water and waste disposal) that they need and deserve. It will also reduce pollution and China's growing demand for energy and other materials needed to fuel its export engines.

Finally, Reich argues that the U.S. needs twenty million jobs and ending currency manipulation by China and other countries alone will not solve that problem. Most analysts agree that eliminating Chinese currency manipulation alone will generate between 300,000 and 1 million U.S. jobs. However, there's no reason to leave those jobs on the table while we search for bigger answers to the unemployment problem.

In fact, eliminating the overall U.S. trade deficit could provide the foundation for rebuilding manufacturing and the U.S. economy and to generating massive employment growth. Eliminating the overall U.S. trade deficit, including most or all of our oil imports, could support three to six million new jobs, or more. But it won't be cheap, and it will not happen overnight. We need massive new investments in clean energy technologies, infrastructure and R&D, to develop new clean energy industries and to rebuild U.S. infrastructure and manufacturing industries. We also need new tools for fighting unfair trade policies such as China's illegal subsidies to its steel, glass, paper and clean energy industries. Taken as a whole, these strategies could eliminate U.S. trade deficits and generate most of the jobs needed to get unemployment down to five percent. But it won't be cheap, or easy.

Attacks from the right

Proposals to punish China for currency manipulation have also been attacked from the right, most recently by Mark J. Perry of the American Enterprise Institute. Perry recently summarized a blog posting by Scott Grannis, former chief economist for a private investment management firm in California, and an acolyte of Arthur Laffer and other supply siders.

Grannis begins by claiming that the yuan is not too weak because it has appreciated 23 percent since 1994, and because inflation has been low in China for some time. Neither of these statements says anything about the appropriate level of the yuan or renminbi (RMB--the official name of China's currency). China maintains closed capital markets and does not allow its citizens to invest abroad. It maintains complete control of the domestic money supply, which is the primary determinate of domestic inflation.

Regardless of what has happened to the value of the nominal value of the RMB since 1994, the fact is that China is egregiously violating every accepted standard of currency manipulation (Scott and Bivens, 2006). It has maintained a large, bilateral trade surplus with the United States for more than a decade, both in dollar terms and as a share of its GDP. China has maintained large global current account surpluses (the broadest measure of all trade in goods, service and income flows). And it has massively intervened in currency markets.

China has purchased $1 billion or more per day in foreign exchange reserves for many years. This is prima facie evidence of currency manipulation. They have acquired $2.5 trillion dollars in reserves, equal to 22 months of import purchases, and far in excess of ratios held by other countries named by the United States as currency manipulators in the past (Taiwan, South Korea, and China itself on two occasions in the early 1990s).

Next, Grannis asks "if the yuan were chronically 'too weak,' what's the problem anyway? ...some manufacturers might go out of business but all consumers would benefit." Perry goes on to claim that if China is forced to appreciate the yuan only a small group of American producers will benefit, but it will harm "all consumers and many businesses." This is sadly confused logic. Unfair trade with China (and other countries) affects the United States in at least three ways--all must be considered to determine whether currency policy will help or hurt most or all Americans.

First, it is critical to remember that consumers are workers, too, for the most part. If imports are cheaper but workers have less to spend because imports and offshoring have depressed their wages, then the ultimate impact of imports on consumers can be negative. And trade with low wage countries like China does affect wages. This is a well known result in trade theory, but one that rarely makes its way into introductory economics textbooks.

Josh Bivens has shown that the rise of import competition from low-wage countries has depressed the wages of manufacturing production workers, and all other workers with similar skills by approximately $1,400 per year for the typical median wage earner. Most manufacturing production workers do not have college degrees, and the group of comparable workers in the economy is composed of all non-college educated production and non-supervisory workers. There are about 100 million such workers and they make up about 70% of the labor force.

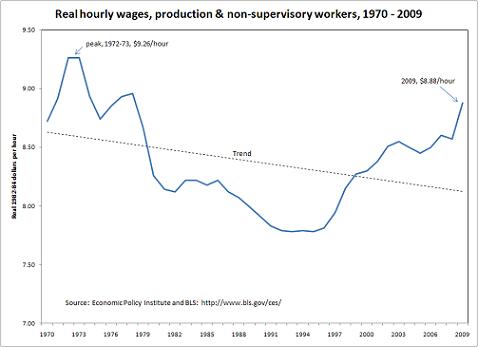

As shown in the Figure below, the real wages of production workers fell significantly between 1973 and 2009. The trend line in the figure shows the tendency of real wages to decline in this period.

(Note: The uptick in production worker wages in 2009 was an anomaly due to the sharp fall in energy prices during the recession. Real Wages are falling in 2010 on a monthly basis, and will likely fall more in the future as long as unemployment remains well in excess of five percent. )

If import prices were falling fast enough to provide a net benefit to production workers, then their real wages would have increased in the past three decades. In fact, they have fallen, as shown in the figure. The bottom line is that globalization and especially unfair trade with China have eliminated millions of U.S. jobs, especially in the past decade, and have contributed to the prolonged decline in the real wages of working Americans. Ending currency manipulation will reduce the downward pressure of globalization on U.S. wages.

The real beneficiaries of cheap goods from China are workers with college degrees, and especially professionals, managers, executives and stockholders. Those in the top 1 percent of all wage earners, who derive most of their incomes from profits, have benefited most of all from globalization. Between 1979 and 2007, before the start of the recession, this group captured 38.7 % of all the income growth in this period (Mishel 2010). Nearly two-thirds (63.7%) of all income gains went to the top 10%, and an additional 11.5% went to the next 10% of all households. Thus, the bottom 80% of the labor force captured only 26.3% of all the gains in income over this three-decade period. The most important effect of globalization, and especially unfair competition with China, has been to redistribute income from working families to those at the very top of the income distribution. It was a battle between Main Street and Wall Street, and multinational corporations captured the lion's share of the spoils in this fight.

The most direct effect of unfair trade is that it causes trade deficits to rise. A new EPI report shows that rising trade deficits with China will cost one-half million U.S. jobs in 2010 alone. Since China entered the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001, the United States has lost 5.5 million manufacturing jobs and more than 26,000 (net) manufacturing plants. China is responsible for at least 2.4 million of those lost jobs. These are concentrated loses, but the costs of unfair trade do not end there.

The Ryan-Murphy currency legislation being considered by Congress is a first step in the fight against currency manipulation. If passed, it would send an important message to China and the administration that Congress will no longer tolerate illegal currency manipulation. However, the legislation would apply to only a small share of total U.S.-China trade--only products subject to countervailing duties might be penalized (fewer than 60 products from China are now subject to antidumping or countervailing duties). It would not necessarily impose duties in particular specific cases--it would merely authorize the Commerce Department to treat currency manipulation as an illegal export subsidy in countervailing duty Investigations. There is growing support for much more aggressive action against Chinese currency manipulation, such as a 25% across the board tariff. If the Ryan-Murphy bill is passed and China does not get the message, then it will soon be time to consider much broader restrictions on Chinese imports.

Disclosure: EPI is a non-profit think tank that receives the majority of its funding from foundation grants but also receives support from U.S. labor unions and industrial associations.