Every week, we bring you one overlooked aspect of the stories that made news in recent days. You noticed the media forgot all about another story's basic facts? Tweet @TheWorldPost or let us know on our Facebook page.

On Friday, Japan marked 20 years since members of a shadowy cult let off deadly sarin nerve gas in Tokyo's subway system. The attack was the worst in modern Japanese history, and prompted global concern about terrorist groups obtaining chemical weapons.

The attack left 13 people dead, and more than 6,000 others suffering the effects of the nerve gas. More than 20 years later, a majority of the victims say they still have vision problems and fatigue.

"The incident isn't over yet because many are still suffering from the after-effects of the sarin," Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe said at an anniversary ceremony on Friday.

Station master Mitsuaki Ota walks to an altar for the victims of the 1995 deadly nerve-gas attack in Tokyo on Friday. (TORU YAMANAKA/AFP/Getty Images)

Station master Mitsuaki Ota walks to an altar for the victims of the 1995 deadly nerve-gas attack in Tokyo on Friday. (TORU YAMANAKA/AFP/Getty Images)

On March 20, 1995, cult members dropped five plastic bags of liquid sarin on subway trains packed with rush-hour commuters in the Japanese capital. In a coordinated attack, the assailants each pierced their packets with metal-tipped umbrellas, releasing the deadly nerve gas.

A New York Times report from the time describes the terrifying scenes that unfolded:

As the trains arrived in stations and opened their doors, passengers staggered out and collapsed on the platforms[...]Subway entrances soon looked like battlefields, as injured commuters lay gasping on the ground, some of them with blood gushing from the nose or mouth. Army troops from a chemical warfare unit rushed to the scene with special vehicles to clear the air, and men in gas masks and clothes resembling space suits probed for clues.

A subway passenger with his mouth covered up by a handkerchief is escorted by masked policemen at Tokyo's Akasaka Station, March 20, 1995. (AP Photo/Itsuo Inouye)

A subway passenger with his mouth covered up by a handkerchief is escorted by masked policemen at Tokyo's Akasaka Station, March 20, 1995. (AP Photo/Itsuo Inouye)

Developed in Nazi Germany in the 1930s, Sarin is one of the most deadly nerve gases in the world. Experts later said the death toll in Tokyo could have run into the thousands if the sarin had been deployed differently.

A commuter is treated by an emergency medical team at a make-shift shelter after inhaling a lethal nerve gas unleashed by attackers in the Tokyo metro system, March 20, 1995. (JUNJI KUROKAWA/AFP/Getty Images)

A commuter is treated by an emergency medical team at a make-shift shelter after inhaling a lethal nerve gas unleashed by attackers in the Tokyo metro system, March 20, 1995. (JUNJI KUROKAWA/AFP/Getty Images)

The attack left Japan reeling. Tensions soared as authorities thwarted a spate of further chemical and gas attacks in the months that followed.

Wearing gas masks, members of the Japanese Ground Self-Defense Forces clean up subway cars late on March 20, 1995 in Tokyo. (JIJI PRESS/AFP/Getty Images)

Wearing gas masks, members of the Japanese Ground Self-Defense Forces clean up subway cars late on March 20, 1995 in Tokyo. (JIJI PRESS/AFP/Getty Images)

Suspicion quickly fell on Japan's Aum Shinrikyo religious cult. Days after the attack, police raided Aum facilities around the country and discovered extensive preparations for chemical and biological attacks.

Hundreds of cult members were arrested. The cult's leader, Shoko Asahara, was finally caught two months later, hiding in a secret room at the cult's headquarters. It took another 17 years for authorities to track down the last two fugitives sought in connection with the attack.

A squad of helmeted riot police moves toward the facilities of the Aum Shinri Kyo sect at the foot of Mount Fuji on Tuesday, March 28, 1995. (AP Photo/Katsumi Kasahara)

A squad of helmeted riot police moves toward the facilities of the Aum Shinri Kyo sect at the foot of Mount Fuji on Tuesday, March 28, 1995. (AP Photo/Katsumi Kasahara)

Nearly 200 members of the cult were convicted in connection with the Tokyo sarin attack and a string of other terror attacks and assassinations. Thirteen of them, including Asahara, are on death row.

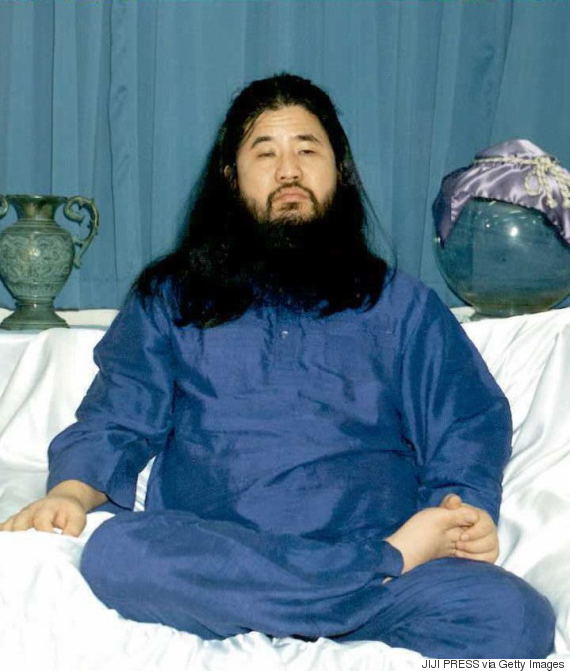

Asahara, who is partially blind, started the cult in the 1980s. Drawing on elements of Christian, Buddhist and Hindu teaching, he declared himself the savior of the world, with supernatural powers. He said the end of the world was near and only his followers would be spared. At its height, his cult was estimated to have around 40,000 followers in Japan and Russia, and was notorious for attracting wealthy and educated recruits.

The leader of the Aum Shinrikyo Shoko Asahara pictured in October 1990. (JIJI PRESS/AFP/Getty Images)

The leader of the Aum Shinrikyo Shoko Asahara pictured in October 1990. (JIJI PRESS/AFP/Getty Images)

Twenty years later, Japan is still grappling to understand the cult's actions. While Asahara hardly spoke during his trial, he did deny ordering his followers to carry out the attack. Japanese authorities said the cult wanted to disrupt an impending police crackdown on the group, as well as to hasten the apocalypse.

Riot policemen wearing gas masks stand by during a dawn raid at a building of the controversial Aum Supreme Truth sect in Kamikuishiki, west of Tokyo on March 22, 1995. (AFP/Getty Images)

Riot policemen wearing gas masks stand by during a dawn raid at a building of the controversial Aum Supreme Truth sect in Kamikuishiki, west of Tokyo on March 22, 1995. (AFP/Getty Images)

Despite the attack, Aum was never banned in Japan. While it was outlawed in Russia and designated a terrorist organization by several countries, Japan opted instead to keep the group under strict surveillance, an order renewed in January for three more years. The group did lose its religious status and was forced into bankruptcy by compensations payments to the victims of the attack. But it lives on in two new offshoots, Aleph and Hikari no Wa, which have an estimated 1,500 followers. They claim to have disavowed Asahara, but many Japanese remain deeply suspicious of their activities.

Photos of Shoko Asahara hang on the walls of the Aum Shinrikyo shrine in their New York office, March 23, 1995. (AP Photo/Osamu Honda)

Photos of Shoko Asahara hang on the walls of the Aum Shinrikyo shrine in their New York office, March 23, 1995. (AP Photo/Osamu Honda)

The victims of the attack insist that Japan must never forgot the events of 20 years ago. "If people who do not know about the incident increase, a similar tragedy will occur again, so I want young people to take interest in what happened,” Shizue Takahashi, whose husband was killed in the attack, told Japanese newspaper The Asahi Shimbun on Friday.