"Addiction" has easily become one of the most stigmatized words in the English language. It invokes a sense of severity. It signifies a medical diagnosis. It indicates that a person needs an intervention -- and soon -- before being lost entirely. But you don't need to be an addict to benefit from the process of recovery.

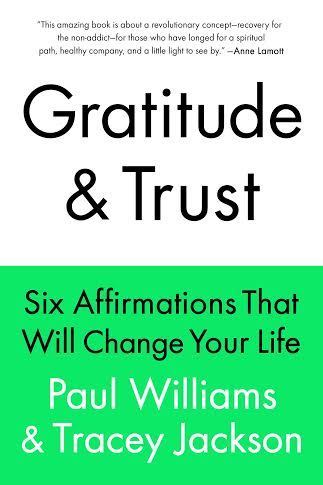

In their latest book, Gratitude and Trust: Six Affirmations That Will Change Your Life, co-authors Paul Williams and Tracey Jackson argue that therapeutic treatment can benefit anyone. No matter the walk of life you come from or the issues you face, the self-reflective recovery process can help you learn critical lessons. Using principles from the traditional recovery movement, the authors, who have become close friends over the past few decades, explain how such practices benefit a person's mental, physical and emotional health regardless of the "A" word -- and share their personal stories to prove it.

Williams is an Oscar- and Grammy-winning songwriter and a recovering addict. While he managed to keep his career in tact through his downward spiral with drug and alcohol abuse, 24 years ago he was forced to face the personal baggage that triggered his addictive behaviors in the first place. Recovery not only proved essential in helping him become the person he is today, but also revealed to him that the principles now guiding his life don't exclusively help people with addictions.

Jackson is a successful screenwriter and author and not an addict. Yet her experiences with traditional therapy -- as well as the recovery needs of many people close to her -- sparked her interest in sharing these helpful tools with people hoping to find productive ways to deal with daily difficulties.

The two friends reconnected several years ago after a screening of Williams's film, "Paul Williams Is Still Alive", when Jackson was itching to write a book on recovery but had yet to discover the right approach.

"I heard him speak, and he mentioned that his choo-choo ran on the twin rails of gratitude and trust, and sitting there in the audience, I just thought, 'That's the book, that's the catchword, that's the phrase,'" Jackson told The Huffington Post. "He had talked a lot about his recovery before, and I had heard him speak about it. He knew I had a lot of friends in recovery, he knew I liked the principles of recovery, but we never really said it. It was kind of an eureka day."

When Jackson approached Williams with the idea, he was equally excited by the chance to provide this information to a broader, more general audience.

"People have been saying they see the remarkable change in my life and the way I accept life on life's terms and ask, 'Why don't we have something like that?'" Williams told The Huffington Post. "When Tracey and I talked about it, all of a sudden we began to identify the difference between an addict who suffers from the life-threatening disease of addiction and people that have life-limiting habits. There's a great variety of things that hold people back from living their best possible lives."

In the text, they weave their individual experiences into information about belief systems from around the world that support the six affirmations holding the guide together.

The first affirmation, "Something needs to change, and it's probably me," is one of the toughest for many people to wholly accept. "It's a natural resistance," said Jackson. "We're trained from an early age in this society that everything is fine, that we should not broadcast our problems, that we should siphon our feelings. A lot of our behavior is engrained subconsciously, and oftentimes people don't even know where to go. They don't have a GPS, they don't have a map, they know something's wrong, they know something doesn't feel right, they know that their life is off-kilter, but they don't have any navigational tools to lead them where to go."

That's where the authors hope the six affirmations, accompanying explanations and small suggested steps will come into play. By focusing on living in the moment, taking it one day at a time and breaking down bigger problems into smaller pieces, we accomplish several things -- we better ourselves, we do it collectively, we help weaken the isolating stigma that says only addicts need or benefit from this type of work. Taking an honest look at ourselves before bad habits become destructive -- or addictive -- can lead to the most helpful discoveries.

Related

Before You Go

The problem with trying something new (like: photography) is that we approach it, hoping for instant success. Instead, write Ryan Babineaux PhD and John Krumboltz PhD in their new book, Fail Fast, Fail Often it helps us to bomb out over and over, each time using the experience to "fail forward." The co-creators of Stanford University's continuing studies course of the same name outline a specific process:

1. Find something that you'd like to try but haven't because you're afraid of splatting on your face. (Example: "I want take pictures for a living.")

2. Find a way to fail at it as quickly as possible. (For example, "I'm going to take pictures at my cousin's wedding next week.")

3. Do it and tell people you're new to this. (For example, "While I'm snapping away, I'll tell everybody I'm a beginner and ask what people think about the shots").

4. Go home and analyze ("What came naturally, and what do I need to work on? What was fun -- and what wasn't?")

5. Set another challenge and fail again ("Next time, I'll take pictures at a wedding and get paid for it"). By the shifting your focus to learning something as a beginner (instead of, say, producing something amazing), write the authors, you will perform better, enjoy yourself more, find ways to learn from your stumbles -- all of which leads you to succeed much more quickly.

The next time you're in a long meeting or conference, consider picking up a pen and drawing weird, flowery, scribbly thingamajigs on the edge of your agenda. Doodling, writes Sunni Brown, whose TED talk on the subject has been seen by more than 1.1 million people, can actually increase your ability to retain and remember information. As she describes in her book Doodle Revolution, when researchers at the University of Plymouth placed people on a monotonous phone call, some of them doodled, others didn't. Later, on a surprise memory test, the doodlers absorbed and recalled 29 percent more of the content than the nondoodlers. "Rather than diverting our attention away from a topic (what our culture believes is happening when people doodle)," says Brown, "doodling can serve as an anchoring task -- a task that can occur simultaneously with another task -- and act as a preemptive measure to keep us from losing focus on a boring topic."

Meaning is what makes us happier (and usually more successful) in our professional and personal lives. And yet we don't always immediately recognize what is most meaningful to us -- which is why Harvard researcher Shawn Achor's designed an experiment called the "happiness graph. How to do it: Think about the last year, then sketch a line graph with two axes, the vertical one for happiness and the horizontal one for time. "So, if you got a promotion in January, and that made you happy, that should be a high point on the graph," he writes in Before Happiness: The 5 Hidden Keys to Achieving Success, Spreading Happiness, and Sustaining Positive Change. "Or, if you were miserable in January but then in early February your football team won the Super Bowl, you'd draw a spike," and so on, all the way through December. Then, label the events that determined your highs and lows.

"The events you include can uncover important yet hidden nodes of meaning in your life," writes Achor. Some people's happiness fluctuates around family events, others around world events, still others around work events. "Whatever our individual graphs look like, they help us understand what parts of our lives our happiness (or conversely, our unhappiness) depends on." The question then becomes: Are you spending your time on your points of highest meaning? And if not, how can you change things in your life to let you focus more on those?

Step 1: Make a list of everything you do at work, write corporate trainers Jones Loflin and Todd Musig, who train Fortune 500 companies in time management and work-life balance. (If you are the director of a candy factory, for example, you might write down: monitor chocolate and butterscotch makers, advise the wrapping designer, plan factory expansion, make sure the tasters don't taste too enthusiastically). As the two describe in Getting to It: Accomplishing the Important, Handling the Urgent, and Removing the Unnecessary, their clients typically start the list with their current workload, then mention other upcoming activities, then lastly remember "all the smaller tasks that dot their plates like peas." After listening to their clients' frustrations for a short while, Loflin and Musig then ask them, "What are you paid to do?" In that moment, the clients usually realize how much of their day is spent on problems they inherited, tasks no one else wants to (or can) do and putting out minor (but avoidable) fireballs.

Step 2: "Dust off your job description," the two write, "and review your most recent evaluation." Make another list of the four or five things you're paid to do. If you give those your full attention, your performance on other to-dos may not matter as much. You'll do better at what your boss needs you most for. P.S. "This strategy," the two write, "also applies to the other roles in your life. What are the three or four things you can do as a parent, neighbor, volunteer, baseball coach, Sunday-school teacher, gardener, son-in-law, dancer, and so on, that make the greatest impact? Three or four key things are doable. Ten or 12 can be overwhelming."

"Let's say a rush of intense anger overtakes you," writes meditation teacher Sharon Salzberg. Normally, as she explains in Real Happiness at Work: Meditations for Accomplishment, Achievement, and Peace, we think about the person or thing that made us mad (for example, "They did this, so I'm going to do that and my vengeful act will destroy them!") or we beat ourselves up (for example, "I'm such a terrible person, I'm so awful. I can't believe I'm so angry. I've been in therapy for 10 years. How could I still be angry?") But what if you could take human beings out of the equation? What if the first thing you said was, "Oh...this is anger." Identifying the feeling allows you to look at the anger (not you or the other person) and, as Salzberg writes, this decreases its power to take over our minds since we stop being busy reacting. What we notice, she adds, is that anger is not just one thing; it is made up of moments of sadness, moments of fear, moments of frustration, moments of panic. Understanding that it is many different things also allows for many different ways to end it.

When we're trying to work a deal -- be it with a contractor redoing the house or a neighbor who wants to split a new power mower -- we usually think of what might go wrong. We may even name a few ideas (such as, the contractor might go overbudget or the neighbor might forget to fill up the mower with gas). But that is not enough, writes Harvard Business School professor Michael Wheeler in The Art of Negotiation: How to Improvise Agreement in a Chaotic World.

Instead, pretend the negotiation has started. Now imagine there's been a major problem. Ask yourself, "What will it be?"(maybe the contractor wants to install a $700 toilet instead of a $100 one, for example). Rather than having a fuzzy idea of something that might go south, you're now assuming something will, which fosters "an attitude of watchfulness, so you'll be quicker to see if/when the process is going awry. If you're alert, you may be able to put it back on track. If not, you'll have a plan B."

Now flash forward again. This time imagine that there's been some sort of wonderful surprise in your talks. What is it? "Studies show that negotiators who set lofty goals get better deals," writes Wheeler, who also edits the Negotiation Journal at Harvard Law School. "Instead of contenting themselves with outcomes they can live with, these negotiators focus instead on how much the other party might be prepared to grant. In addition, imagining upside scenarios prepare you to recognize opportunities and find creative solutions."

The breakneck pace at which we move today has become as seductive as alcohol or drugs, writes addiction specialist and psychologist, Stephanie Brown, PhD, in Speed: Facing our Addiction to Fast and Faster and Overcoming Our Fear of Slowing Down, not to mention it sucks us into stress levels that can impair our immune systems and "even rewire the brain, leaving us more vulnerable to anxiety and depression." Her favorite solution, which she borrowed from a client who grew up in Oregon where families leave wet boots in a mudroom by the front door: Create a space by your entrance where everyone places their cell phone, tablets and laptops before coming inside. Then set up tech-permissible times (say, after homework but before dinner) and tech-free times (say, Sunday nights). Watch what happens, including the sentences that result without one embarrassing auto correction.