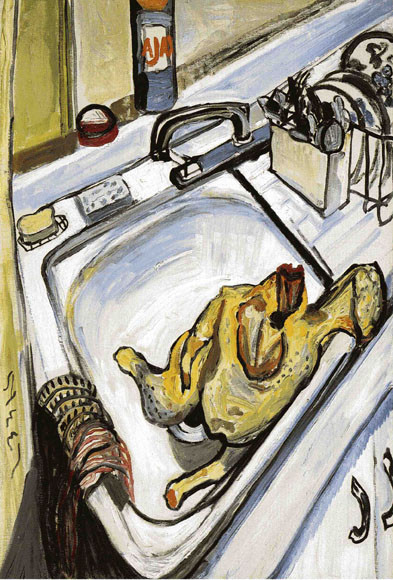

On a free afternoon during a recent lecture trip to Eugene, Oregon, I stopped by the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art to see the traveling exhibition of a contemporary Chinese artist Xiaoze Xie only to spend most of my time in the galleries in front of Alice Neel's unusual and timely "Thanksgiving" painting from the mid-1960s. The artwork's focal point is a contorted body of a plucked and decapitated capon at the bottom of a kitchen sink. The fowl's hips are twisted, revealing a thigh on one side with only a drumstick on the other. Its right wing is pointing into the drain, its left wing resting over the sink's rim, creating the illusion that the dead bird is straining to climb out of its awkward enclosure.

Alice Neel, Thanksgiving, 1965, Oil on canvas, 36 x 24 in (c) The Estate of Alice Neel, Courtesy David Zwirner, New York, Collection of Jonathan and Monica Brand

As I pondered the strange pose of the capon I noticed several other oddities. The space around the sink was uncharacteristically, almost suspiciously tidy for a Thanksgiving-day kitchen, with plates and forks resting in their proper slots on the drying rack, sponges and a soap dish neatly tucked away. In a bold and unambiguous emblematic reference to the birthplace of the holiday, a dish towel is hung out to dry over the left edge of the sink, its patterned folds evoking Old Glory's stars and stripes. We can still make out the characteristic red and white design, but, tellingly, now placed below rows of tiny black dots--the burnt out remnants of formerly white, bright and shiny stars. In the background, a modern chemical miracle--a container of Ajax looms large, making for an unappetizing combination with the capon, and reminding the viewers about the indispensability of the latest consumer goods in a nod to Pop Art's prominence during the 1960's.

While they share the same subject matter, the content of Neel's work could not be further away from Norman Rockwell's famous "Freedom From Want" (a.k.a. "The Thanksgiving Painting"), which appeared in The Saturday Evening Post on March 6, 1943. In his idyllic depiction a perfect family is about to commence a perfect feast in a sun-filled room, with the plump and golden turkey presented by the proud, smiling grandparents.

Norman Rockwell, Freedom From Want, 1943, oil on canvas, 45.75 × 35.5 in, Norman Rockwell Museum

Rockwell's "Freedom From Want" came as a response to F.D.R.'s wartime State of the Union Address delivered in January of 1941, in which the "Freedom from Want" was listed among the four freedoms to be enjoyed by the American people along with the "Freedom of Speech," the "Freedom from Fear" and the "Freedom of Worship." When it was published in The Saturday Evening Post just over two years later, the "Freedom from Want" image became an inspiration to millions of Americans who shared in the dream of prosperity, homeliness and abundance.

Just a quarter of a century later, with the country once again mired down in a war, Neel eschewed Rockwell's American dream as she presented an altogether new version of the holiday: a grotesque and lonely bird, strung-out in a stainless kitchen sink whose cold steel surface recalls a morgue gurney. No longer a delectable centerpiece to the most important meal of the year, a meal meant to bring together families all across the country for a day of celebration of plenty, Neel's bird is its own parody reinforced by the proximity of the American flag as a flaccid kitchen towel, and an icon of modern commodity, Ajax cleaning powder, as a surrogate side dish. Her painting is a Thanksgiving nightmare next to a Thanksgiving dream envisaged by Rockwell.

Although Neel's image could simply represent the other side of Thanksgiving—the interior of loneliness and domestic dysfunction hidden behind the exterior of Rockwell's postcard façade (Clint Eastwood's recent biopic "J. Edgar" has demonstrated that loneliness and dysfunction are as much a part of American identity as anything else)—I would propose a more sinister explanation for the differences between the two picture versions of the favorite American holiday. With the latest data on poverty in the US confirming that the "Freedom From Want" remains elusive for so many, the all-pervasive anxiety of Neel's account seems to reflect today's reality more accurately than Rockwell's much-loved but increasingly utopian vision. According to the numbers reported by the Census Bureau in mid-September, in 2010 over 46.2 million Americans were living below the poverty line (with 2.6 million joining the ranks in the last year alone). This is the highest number since 1959, the year of the US involvement in Vietnam, the very epic war that set the mood for Neel's remarkable painting. As we are preparing for yet another wartime Thanksgiving we might want to consider what it would take for all Americans to finally be able to celebrate the holiday Rockwell style.