The following is an excerpt from Dataclysm: Who We Are When We Think No One’s Looking by Christian Rudder. Rudder is a co-founder of OkCupid, and the operator of OkTrends, a blog that analyzes data culled from the site. The below essay analyzes whether Twitter's word count restriction is shrinking our vocabulary.

When you want to learn about how people write, their unpolished, unguarded words are the best place to start, and we have reams of them. There will be more words written on Twitter in the next two years than contained in all books ever printed. It’s the epitome of the new communication: short and in real time. Twitter was, in fact, the first service not only to encourage brevity and immediacy, but to require them. Its prompt is "What’s happening?" and it gives users 140 characters to tell the world. And Twitter’s sudden popularity, as much as its sudden redefinition of writing, seemed to confirm the fear that the Internet was “killing our culture.” How could people continue to write well (and even think well) in this new confined space -- what would become of a mind so restricted? The actor Ralph Fiennes spoke for many when he said, "You only have to look on Twitter to see evidence of the fact that a lot of English words that are used, say, in Shakespeare’s plays or P. G. Wodehouse novels... are so little used that people don’t even know what they mean now."

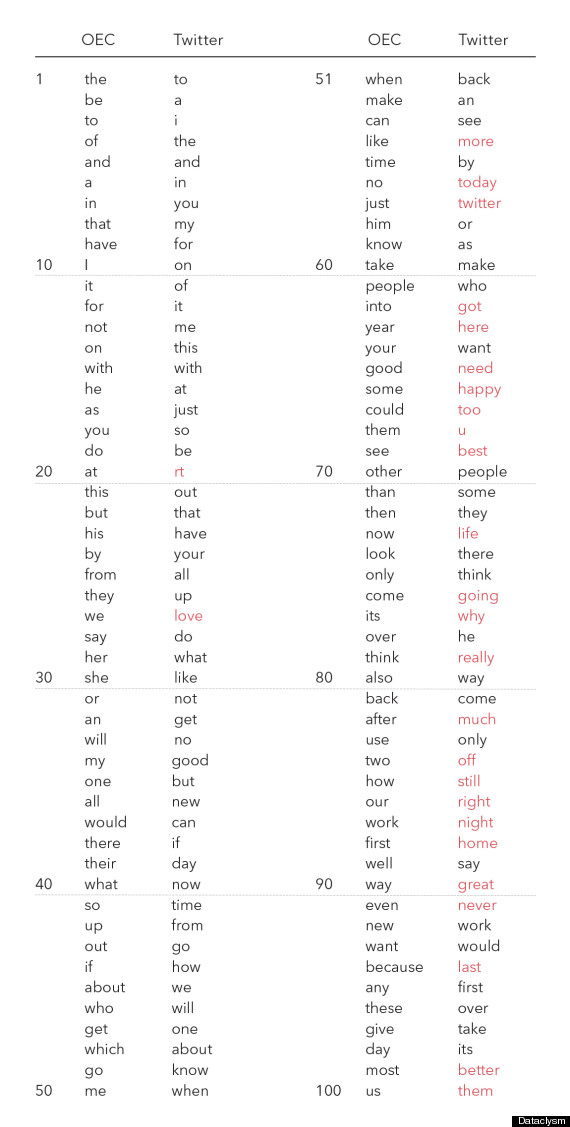

Even basic analysis shows that language on Twitter is far from a degraded form. Below, I’ve compared the most common words on Twitter against the Oxford English Corpus -- a collection of nearly 2.5 billion words of modern writing of all kinds -- journalism, novels, blogs, papers, everything. The OEC is the canonical census of the current English vocabulary. I’ve charted only the top 100 words out of the tens of thousands that people use, which may seem like a paltry sample, but roughly half of all writing is formed from these words alone (both on Twitter and in the OEC). The most important thing to notice on Twitter’s list is this: despite the grumblings from the weathered sentinels atop Fortress English, there are only two "netspeak" entries -- rt, for "retweet" and u, for "you" -- in the top 100. You’d think that con-tractions, grammatical or otherwise, would be staples of a form that only allows a person 140 characters, but instead people seem to be writing around the limitation rather than stubbornly through it. Second, when you calculate the average word length of the Twitter list, it’s longer than the OEC’s: 4.3 characters to 3.4. And look beyond length to the content of the Twitter vocabulary. I’ve highlighted the words unique to it in order to make the comparison easier:

While the OEC list is rather drab, lots of helpers and modifiers -- workmanlike language to get you to some payoff noun or verb -- on Twitter, there’s no room for functionaries; every word’s gotta be boss. So you see vivid stuff like love, happy, life, today, best, never and home make the top 100 cut. Twitter actually may be improving its users’ writing, as it forces them to wring meaning from fewer letters -- it embodies William Strunk’s famous dictum, Omit needless words, at the keystroke level. A person tweeting has no option but concision, and in a backward way the character limit actually ex-plains the slightly longer word length we see. Given finite room to work, longer words mean fewer spaces between them, which means less waste. Although the thoughts expressed on Twitter may be foreshortened, there’s no evidence here that they’re diminished.

Mark Liberman, a professor of linguistics at the University of Pennsylvania, concluded much the same thing: in a direct response to Mr. Fiennes, he calculated the typical word length in Hamlet and in a collection of Wodehouse’s stories (4.05) and found them both less than the length in his Twitter sample. He’s just one of many comparative linguists who’ve begun mining Twitter’s data. A team at Arizona State was able to reach beyond word count and length, and into the sentiment and style of the writing, and they found several surprising things: first, Twitter does not change how a person writes. Among the many examples they tracked, if a writer uses “u” for the second person in e-mails or text messages, she will also use it on Twit-ter. But, likewise, if she generally spells out “you,” she does so every-where -- on Twitter, in texts, in e-mail, and so on. The decision to refer to the first-person singular as "I" or "i" follows the same pattern. That is, a person’s style doesn’t change from medium to medium; there is no “dumbing down.” You write how you write, wherever you write. The linguists also measured Twitter’s lexical density, its proportion of content-carrying words like verbs and nouns, and found it was not only higher than e-mail’s, but was comparable to the writing on Slate, the control used for magazine-level syntax. Everything points to the same conclusion: that Twitter hasn’t so much altered our writing as just gotten it to fit into a smaller place. Looking through the data, instead of a wasteland of cut stumps, we find a forest of bonsai.

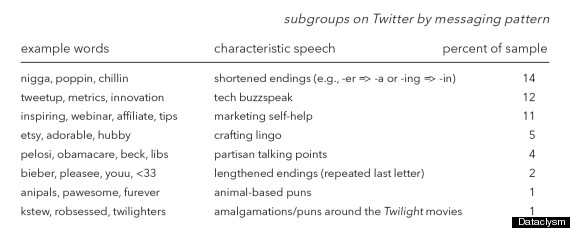

This kind of in-depth analysis (lexical density, word frequency) hints at the real nature of the transformation under way. The change Twitter has wrought on language itself is nothing compared with the change it is bringing to the study of language. Twitter gives us a sense of words not only as the building blocks of thought but as a social connector, which indeed has been the purpose of language since humanity hunched its way across the Serengeti. And unlike older media, Twitter gives us a way to track those bonds on an individual level. You can see not only what a person says, but who she says it to, when, and how often. Comparative linguists have long traced group commonalities through language. Basic words often share common sounds (like tres, trois, drei, three, and thran, from Spanish, French, German, English, and India’s Gujarati) and those stems have given us a sense of the movements of genes and culture across the face of time. Researchers are already grouping people by the language they use on Twitter. Here I’ve excerpted an early attempt to find the tribes and emerging dialects -- this is from a corpus of 189,000 tweeters sending 75 million tweets among them.

It’s important to note that the study grouped users by their words alone, who they messaged, and what they wrote -- these language clusters were not determined a priori. The top-listed group is in fact the largest the researchers detected, and it also happens to be the most voluble (sending the most tweets per capita) as well as the most insular. Some 90 percent of the tweets sent by the group are directed within it, and its users’ language is most strongly "characteristic" -- half of their 100 most representative words fit the “shortened endings” pattern. Throughout the list you see groups typified by slang, pop culture references, jargon, goofy puns -- people drawn together by special ways of speaking, and it’s exactly the kind of language (and information) that until now has been lost to history. Like knowing a man’s last words to his wife, knowing how people talk among friends gives you a much deeper sense of who they are. Technocrats, political wonks, marketing gurus, the robsessed; it will be interesting in the coming years to see how all these groups merge and recombine, and we’ll be able to track it all through their text.

Reprinted from the book DATACLYSM: Who We Are When We Think No One’s Looking by Christian Rudder. Copyright © 2014 by Christian Rudder. Published by Crown, a division of Random House LLC, a Penguin Random House Company.