"We won't kneel and we won't kneel. Bring your airplanes and your guns. But we won't kneel oh Bashar. This Revolution is a revolution of glory."

I hadn't been to Syria since August 2010, seven months before the start of the Revolution. In the ensuing two and a half years, I watched from afar, torn between the idealistic rhetoric of a glorious revolution and warnings of Western imperialism and intervention.

Even before arriving in Syria, it was clear the Syria of 2010 was long gone. On my flight to Southern Turkey, I sat next to a Free Syrian Army fighter. While I was going into Syria as a witness, he was going to fight, leaving his home, comfortable life and prosperous businesses behind. As we deboarded, I wished him safety. "I'm content," he responded, "I either die as a martyr or I live to see Syria free. Once Bashar is ousted, I'll let the politicians take it from there." In 2010, I could have never imagined speaking to another Syrian -- a fighter much less -- about martyrdom, freedom and the ouster of Assad. But this was the Syria of 2013.

I entered Syria through Atmeh Camp, the largest camp for internally displaced Syrians. Housing approximately 20,000 Syrians, Atmeh is primarily funded by private donors and organizations. Unlike Za'atari in Jordan and Killis in Turkey, no government runs this or the other camps in Syria as evidenced by the pure dysfunction and abject poverty of the camps. While many, if not most, in the camps are there to escape death and destruction, I was surprised to learn that others were there because they could no longer afford the daily costs of living. I was told that at least in the camps there was food (even if some of it was spoiled) and some basic humanitarian assistance.

Since the start of the Revolution, the Syrian currency has plummeted in value. Where in 2010, one U.S. dollar was valued at 45 liras, at present it's valued at approximately 215 liras. Prior to going into Syria, the Turkish currency exchanger joked: "next time you should bring a suitcase to carry your Syrian liras."

The devaluation of the Syrian lira coupled with international sanctions and the government's destruction of its own industries has resulted in unprecedented unemployment rates. In the areas I visited in northwestern Syria, most of the businesses were closed or destroyed. The lucky few with functioning businesses supported dozens of family members. And the unlucky many who lost their businesses lived off life savings or even moved to one of numerous camps in Turkey or Northern Syria.

Life in the IDP camps is brutal. The heat, dust, insects and filth coupled with the destitution of the refugees create a fester-pool of anger and hopelessness. In true Darwinian style, survival in the camps is for the fittest or at least, the most cunning -- those first in line for distribution, those with connections to the camp management or those with businesses that charge upward of three times as much on goods as prices in Syrian cities. Four and five year olds speak with the same frustration as adults, condemning both Assad, who destroyed their towns and brutalized their families, and the Revolution, which failed to deliver its promises of freedom and democracy. None of the glories of Revolution are apparent in the camps and no person pontificated on the dangers of Western intervention. Rather, the refugees shooed flies, cursed Assad, cursed the Revolution and then cursed the world that had turned a blind eye to their misery.

Traveling into "liberated" (i.e. rebel-controlled) Syria, I was initially struck by the appearance of normality. Olive groves bloomed, kids played on the street and food and drink stands peppered the roadways. Absent were the pictures and statutes of Bashar and his father Hafez al-Assad that I had come to expect from my many trips to Syria. Also missing were the regime flags and any other sign of Baathist rule.

The deeper we went into Syria, though, the more abnormal things became. Tinted and unlicensed SUVs with the insignia of a Free Syrian Army (FSA) or Islamist brigade were readily prevalent. Men with guns strapped to their backs wearing military fatigues and long beards rode on motorcycles. Demolished factories and bombed stores were more frequent sights than open and functioning stores. And FSA checkpoints secured the entry and exit points of most towns. As we drove deeper into Idlib Province, I found myself thinking of Dorothy's line in the Wizard of Oz: "Toto, I've a feeling we're not in Kansas anymore."

Entering Kafranbel -- a small yet internationally-known town due to its witty posters and weekly protests -- I was awestruck by the painted walls with messages of "rEVOLution".

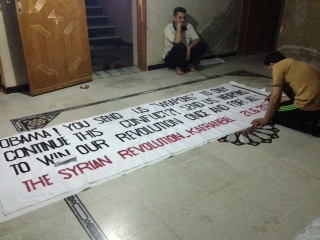

The media center was abuzz with foreign journalists and local activists as they prepared their posters for the Friday protest. The English and Arabic posters as well as the drawings depicting Barack Obama and Vladimir Putin were calculated to speak to local and global audiences. The activists spent hours strategizing how best to express their dissatisfaction with the U.S.'s failure to provide anti-aircraft missiles and heavy weaponry that could strike down government planes that terrorized the "liberated" areas.

Yet in the subsequent days, I experienced the more honest banality of life. Despite not having a physical presence in the "liberated" areas, the government still controlled the utilities and cut the electricity for 20 or more hours a day as both a carrot (a reminder that it remained in power) and a stick. There was no phone service and Internet was rare; jobs were even rarer. At times, it seemed that the only activity was in the sky from helicopters transporting soldiers or dumping loads of explosives on "liberated" towns or in the hospitals that assumed the consequent casualties. As we lazily sat around during the long hot summer days drinking one cup of sweetened tea after another and doing little else, I was surprised to hear Syrians state they had "no time." I soon understood that it was not the physical demand for time but the lack of mental clarity for solutions to the intractable conflict that had left Syrian towns with no formal governance and little resources; their residents, without exception, were left psychologically scarred and emotionally taxed. As one young man expressed to me: "everyone wants to train me in transitional justice and documenting human rights abuses but no one has offered to train me on how to overthrow the Regime. It's been over two years and I still don't know how to do the very thing that got me involved in this Revolution in the first place." Unfortunately there is no manual on Ousting Dictators for Dummies and I too was at a loss for a solution. Other activists expressed regret that there had not been a revolution of thought -- a period of enlightenment and education -- before this Revolution of action. When faced with the overwhelming feat of creating a civil society from scratch, addressing the growing physical and psychological needs of the people and avoiding death by government missile or bullet, it was true; there was very little time.

It is hard, if not nearly impossible, to describe what it's like to be indiscriminately targeted for death or mutilation. While I had previously visited other war zones, I had never experienced the terror of having one's own government wage a full-scale war against its people. Early one Thursday morning while in Kafranbel, I awoke to heavy shelling. My Syrian host, who was now accustomed to the shelling, urgently told me to hide in the bathroom underneath the attic. "The government is warning us not to go out to the demonstration tomorrow," she explained. "They are definitely going to shell us tomorrow." While she had worn her pajamas to sleep that night, she often slept in her clothes in case she had to flee.

In Saraqeb, I was told that it was not the shelling that scared its residents; it was the military planes and explosive barrels that frightened them. "The first shell is the most dangerous," told me a Saraqeb resident. "You don't know where it will land. After the first shell, you run indoors for protection and it's much safer. There's nothing to protect you from explosive barrels though. They can wipe out an entire building and even a street. If you go indoors, the whole house will fall on you. So now, every time we hear a helicopter or military plane overhead, we go outdoors and watch it. We have a higher chance of survival if we are outdoors." As this man spoke, I remembered a picture on Facebook of a group of Syrian men and young boys pointing at the sky with mixed looks of anger and horror.

Residents had only recently returned to Saraqeb when I visited, after months of fleeing to neighboring towns or hiding in the surrounding mountains to escape the government's incessant shelling. The broken streets, destroyed alleyways and decimated buildings were a testament to the government's onslaught. Saraqeb's main street was lined with bags piled seven feet tall full of sand to protect the storefronts from shrapnel. Like the other cities and towns I visited in "liberated" Syria, there were no government soldiers, no pictures of Bashar or government flags. The only reminder of Baathist rule came in form of Russian shells, scud missiles and explosive barrels dropped from the skies above.

On one of my trips to Saraqeb, I stopped at a bakery and was met with the stares of approximately twenty male foreign fighters eating ice cream no less. While I placed my order, a young foreign fighter wearing a turban, black eyeliner, military fatigues and an array of weapons interrupted me and told the Syrian storeowner in classical Arabic, "You are exploiting us with your ice cream prices." The unarmed owner, far outnumbered by his foreign clientele, responded without fear, "Don't tell me that I am exploiting you. I need gas to operate the generator so you can buy ice cream. When you lower the price of gas, I will lower the price of my ice cream." The foreign fighter muttered something about the coming of the Islamic era and walked out.

Through that interaction and others that I witnessed, it was clear that the Syrians did not welcome these foreign Islamists and viewed them as an evil, only second to the Syrian Regime and its allies. Indeed many Syrians suspected that there was a partnership of sorts between the "Islamiyeen" and the Regime. "While the Regime constantly targets FSA military posts," explained a Syrian man from Kafranbel, "it never targets the Jubhat or Dawlat's military posts."

None of the Syrians I spoke with knew the exact nature of the relationship between the Regime and the "Islamiyeen" but they strongly believed the Regime wanted them in Syria. "They substantiate the government's story that it is fighting terrorists," explained one man. "But rather than targeting them, the government shells us, its own people." The "Islamiyeen" also became the international community's scapegoat for declining to intervene in Syria or provide weapons to the moderate FSA. "What, the Islamiyeen are only about 9,000 fighters while the FSA are about 100,000 fighters!" told me the same man. "Yet America only talks about the Islamiyeen as if everyone else in Syria doesn't count." And of course, the "Islamiyeen" have little loyalties to the Syrians in the "liberated" areas and justify their extremist views and harsh dealings on archaic notions of religion and religious statehood. The Dawlat (ISIS) kidnapped a young Syrian videographer and activist I had met a day earlier because he wore a Metallica shirt and expressed irreligious sentiments in his private videos. To this day, his whereabouts remain unknown.

As I left the bakery, I jokingly asked my Syrian hosts if we had accidently driven to Afghanistan rather than Saraqeb. "Don't worry," one of them responded, "they are not welcome here and we won't let them stay in Syria once the Regime falls."

Had I been told in 2010 that the next time I visited Syria, it would be in the midst of a two and a half year Revolution, I would have surely scoffed. Or in the face of that uprising, the Regime would kill over 100,000 (and counting) of its own citizens using chemical and other lethal weapons, and injure, maim, imprison and displace millions more. That the seemingly apolitical and often physically unfit Syrian men of 2010 would come together in the ensuing two and a half years to form poorly-trained and poorly-equipped FSA brigades. And indeed these men would fight government soldiers and tanks to "liberate" the towns and cities I visited in Northwestern Syria as well as other areas throughout Syria. Or that the young women sitting in the cafes and students attending universities were soon-to-be hardened activists who would risk life and limb to stay in Syria, rather than travel abroad, and develop psychosocial programs for internally displaced families or free weekly magazines promoting democracy and civil society or schools for children who had not attended in over two years. Nor could I have imagined the international community's reaction would be calculated inaction in the face of Russia, Iran and Hezbollah's unabashed financial and military support of the Syrian Regime.

And had I known in 2010 that in seven months Syrians would rise up to demand freedom, chanting revolutionary slogans: "We won't kneel and we won't kneel. Bring your airplanes and your guns. But we won't kneel oh Bashar. This Revolution is a revolution of glory", I would have paused -- even for a moment -- to bid farewell to a country that would be forever transformed and to those who would rise up only to find ultimate freedom in death.

But as the saying goes, hindsight is 20/20, and now in 2013 I finally know.

CORRECTION: This post originally stated that the author's most recent visit to Syria was in 2009. It was in 2010.