To meet the challenges of climate change and infectious diseases, we might find the best answer by revisiting a stunningly successful model: the Manhattan Project. In 1939 the United States initiated a bold and ambitious program to develop an atomic bomb. At the time, scientists knew little about splitting the atom.

In establishing the Manhattan Project, the U.S. did not apply the knee-jerk capitalistic model of mobilizing competition. Had we succumbed to that model, the government might have offered grants and other incentives to encourage individual scientists, universities, private and publicly held companies to compete in a race to develop the bomb -- with benefits to the winner.

Why didn't we go that route? It was well known that Germany was working furiously on developing an atomic bomb and had made significant progress. President Franklin D. Roosevelt feared Nazi Germany beating us to the bomb and bringing the entire world to its knees. It was a desperate emergency which called for objective logic, not the replay of doctrinaire political and economic ideologies. And that logic dictated the best probable path for achieving success.

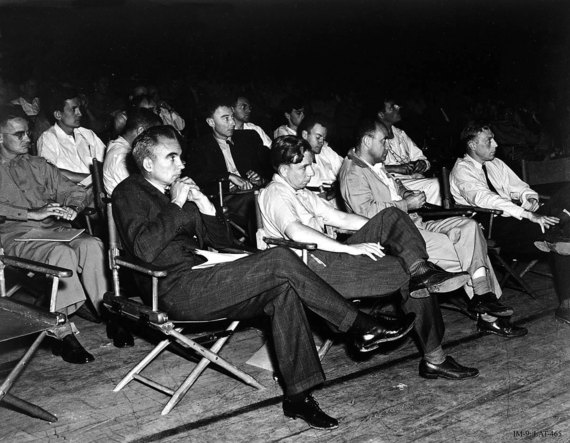

The Manhattan project brought the most brilliant physicists and other scientists and managers from around the world to a campus in Los Alamos, New Mexico, where they worked intensively and cooperatively. Teams labored on different aspects of the thorny theoretical and engineering conundrums, frequently sharing progress and results. Two demanding and determined overseers -- General Leslie Groves and physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer -- constantly reviewed developments to shape strategies for moving in the most fruitful and promising directions. This was a far cry from the usual pattern of companies working in isolation and secrecy to protect their findings in the hope of making discoveries and then obtaining patents to reap huge financial rewards.

Starting with scant knowledge about splitting the atom, the Los Alamos-centered Manhattan Project achieved its goal in a mere six years -- and at a cost of $2 billion, which is about $26 billion in today's dollars. Juxtapose that with the $180 billion that the U.S. government spent to bail out AIG in 2008. What was the benefit to mankind of that dole?

How long have scientists been working on a cure and vaccine for AIDS and how much have we spent? How long have we sought alternative energy sources to save the planet and how much has that cost? Decades, and billions far in excess of the cost of the Manhattan Project -- and we still have no solutions for these crises. Is the problem our addiction to a failed model and our unwillingness to adopt a proven model, the Manhattan Project.

On June 8, 2014, I attended a press briefing at the United Nations on international progress in cutting carbon emissions. Ban Ki-moon, Secretary General of the United Nations, was first to step to the podium. He made the encouraging announcement, based on the Pathways to Deep Carbonization Report, that major carbon emitting countries will be signing an agreement to cut carbon emissions by mid-century "enough to limit human induced temperature rise to the globally agreed goal of less than two degrees Celsius." A rise of two degrees, according to the report, "constitutes a serious threat to human well-being."

The Secretary General's announcement was soon deflated when Jeffrey Sachs, director of Columbia University's Earth Institute who led the panel discussion on the report, said that the commitments of various countries are not likely to be met. More disturbing, Sachs warned that the world is heading toward an increase of four degrees or possibly more. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, a four-degree rise "would pose dangers that might exceed the abilities of societies to adapt, including crop failures, drastic sea-level rise, migration of diseases, and extinctions of ecosystems." Thus, even if the target for carbon reduction is met, it will not be commensurate with the projected devastating global rise in temperature.

The report also cites progress in the development of alternative non-carbon or low-carbon emission technologies but emphasizes that for further progress "we need accelerated research, development, demonstration, and diffusion of these emission reducing technologies to make them reliable, cost-competitive, and widely available in every country." How will these goals be accomplished? Again we are caught wedded to the fragmentation model of appealing for solutions from individual countries, individual entrepreneurs, corporate and private entities. With life on the planet at stake, doesn't a cooperative international effort like the Manhattan Project make more sense?

The world is immediately struggling to cope with the Ebola crisis, an infectious disease for which there is no cure or vaccine. The black plague, which swept across Europe in the 14th century killed 20 million people -- a third of the population of the continent. If the Ebola virus became readily transmittable through the air the world could face a similar fate. Even if the Ebola virus quickly disappears, scientists have warned that other lethal viruses may surface in the future. Like the current disorganized response to the Ebola threat, will we scramble and fumble to address new threats?

Isn't it time to establish an infrastructure like the Manhattan project? Such a structure could respond quickly to crises by assembling the most talented scientists in one location -- and others through technology hookups -- to work jointly on solutions.

We know more about energy and infectious diseases than we knew about splitting the atom when the Manhattan Project was launched. But we don't have the structure to capitalize on that knowledge. We could if we muster the will and courage to establish it. If not, we will continue to worship at the altar of the competition model and may discover too late that we have defended a flawed doctrinaire ideology to our death?

Note: There were actually several secret locations for the Manhattan Project. Los Alamos was the main and central command location.

Bernard Starr, PhD is a psychologist and professor emeritus at the City University of New York, Brooklyn College. He is also the main United Nations representative for the Institute of Global Education (IGE) that founded Radio For Peace International and the Mucherla Global School in Mucherla, India.