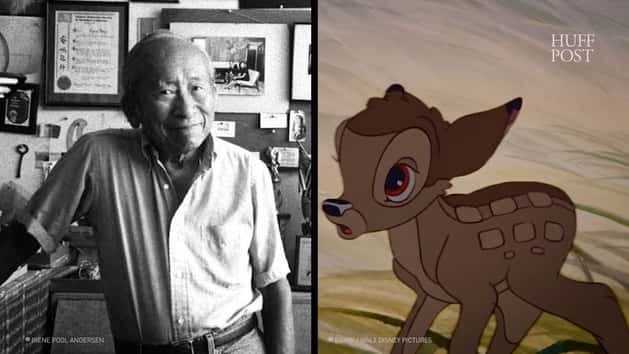

Tyrus Wong, the historically unrenowned artist who created the lyrical, elegiac aesthetic for Walt Disney’s “Bambi,” got his artistic start in the 1920s by dipping a brush in newspaper ink because he couldn’t afford art supplies.

Wong, who died Friday, Dec. 30 at the age of 106, was a Chinese immigrant artist who unofficially served as the lead illustrator for “Bambi.” The muted hues and sparse forest imagery that critics praised in the 1942 film represent Wong’s invocation of Song (Sung) Dynasty in his work. Wong has said the golden era of Chinese painting and pottery ― which lasted from 960-1279 and features landscapes, birds and flowers created from short, minimal brushstrokes ― inspired his work on the film.

Yet Wong was only credited as a “Bambi” background artist by Disney, where he started working in 1938. He finally received the recognition critics say he deserved in his 90s when he was named a a “Disney Legend” in 2001.

Fine artists, filmmakers, Asian-Americans and people of color say he was truly a luminary.

“Tyrus is not a footnote by any means,” Pamela Tom, director of the award-winning documentary “Tyrus,” told The Huffington Post.

Tom said there are a number of theories as to why he went unrecognized, but she pointed to racism as a primary reason, given the existence of the Chinese Exclusion Act early in his career. The law prohibited immigration of Chinese laborers from 1882 to 1943 and was the first time an entire ethnic group was banned from coming to the U.S.

““He had a lot of dignity, but he also felt the pangs of racism."”

“In the ‘20s and ‘30s in Chinese-American communities, what could you hope to achieve?” the documentary “Tyrus” queries. “You could become a laundromat, a houseboy or work in a restaurant. To be an artist was not a remote possibility.”

Wong himself had expressed that he was on the receiving end of racism, detailing how he was called a “chink” by his art director at Republic Pictures, a production company that closed in 1959.

“He had a lot of dignity, but he also felt the pangs of racism,” Tom told HuffPost. “I think Tyrus represents success. He represents someone who’s a survivor, who broke these racial barriers.”

Wong left his mother and sister in China at the age of 9 to move to America with his father. They emigrated to the San Francisco Bay in 1920, hoping for a better life. After arriving at Angel Island Immigration Center, Wong would never see his mother and sister again.

“There were no other kids besides myself, so no playmates,” Wong said in an Angel Island profile. He traveled as a “paper son,” using false documents that claimed he had relatives who were U.S. citizens, the “Tyrus” documentary recounts. He was forced to wait in barracks on the island for interrogation and was separated from his father for two weeks.

“I’m wondering most of the time about my father. I said, ‘What happened to my father?’ All of the sudden I don’t see him. I ask the guard what happened, and I don’t speak English, so I just suffered,” he said in the Angel Island video.

“The Angel Island experience is a very painful chapter in Chinese American history, a hidden chapter,” Eddie Wong, executive director of the Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation, told The Los Angeles Times.

Wong and his father would later be reunited and go on to live in a vermin-infested apartment in Chinatown in Los Angeles. While in junior high, the aspiring artist attended Otis College of Art and Design on a scholarship. He was so talented that he left his public school altogether for the institute after his father pulled together the necessary $90 tuition fee.

“I think that we would not have Tyrus Wong and his art had he not gone through the kind of struggle that he had.”

Critics have pointed out similarities between Wong’s artwork and his own life, such as the plot in “Bambi” and his own separation from his mother.

“I think that we would not have Tyrus Wong and his art had he not gone through the kind of struggle that he had,” Tom told HuffPost. “There’s a loneliness to his work. That’s totally reflective of the losses he experienced early in his life.”

Wong got his big break when he was working at Disney as an “in-betweener,” or someone who drew the images that helped bring the animation to life. When he heard that “Bambi” was in pre-production, he went home, read the book, and developed sample paintings evocative of the mood and tone.

At the time, Disney was attempting to emulate the finely tuned background detail used in “Snow White,” a style that rendered the deer in “Bambi” completely camouflaged, The New York Times reported. When Walt Disney himself got ahold of Wong’s subtle watercolor images, he personally selected him as the unofficial inspirational sketch artist for the film. This meant everyone working on the animated movie took his vision as art direction.

“Walt Disney went crazy over them,” animation historian John Canemaker told The Times. “He said, ‘I love this indefinite quality, the mysterious quality of the forest.’”

“In this day and age of strong anti-immigrant and racist rhetoric, had Tyrus been sent back to China ... we would have no Bambi.”

Besides Wong’s personal influence on the film, Tom points out that his life provides other critical lessons that resonate today.

“In this day and age of strong anti-immigrant and racist rhetoric, had Tyrus been sent back to China ... we would have no Bambi.”

The documentary “Tyrus” will air on PBS this summer.

Every Friday, HuffPost’s Culture Shift newsletter helps you figure out which books you should read, art you should check out, movies you should watch and music should listen to. Sign up here.