Sitting pertly on a low-standing couch, Ultra Violet is but one of the many violaceous bursts of color in her Chelsea art studio. As expected, she is dressed in her signature shade of purple, surrounded by similarly colored sculptures, mirrors and canvases that litter the studio's floor and crawl up its corners. The famed '60s icon, remembered by most for her association with the enigmatic pop-master, Andy Warhol, has invited us into her private world just one week before the 84th anniversary of Warhol's birth. In commemoration of her former companion, she has agreed to discuss with us something she rarely consents to addressing -- her past.

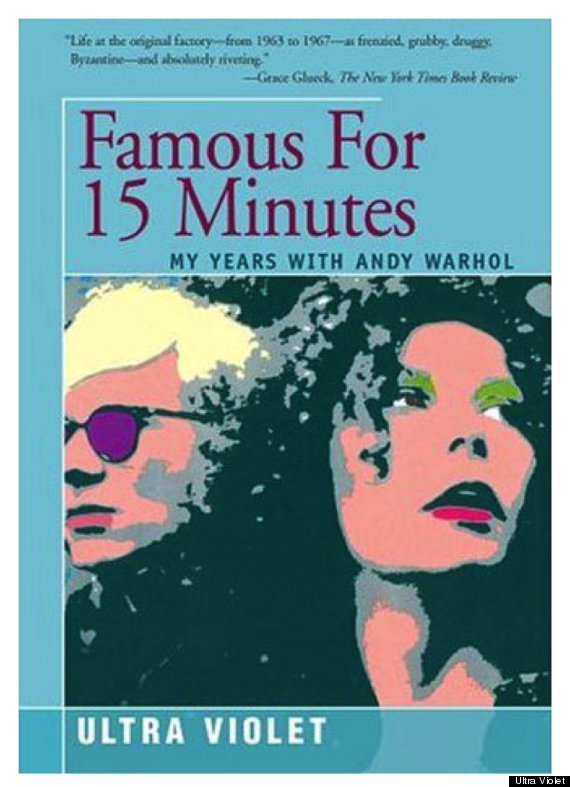

In her 1988 memoir, "Famous For 15 Minutes: My Years with Andy Warhol", Ultra Violet detailed the chaotic years of living with Andy Warhol and the eccentric members of the Factory. She found herself a "Superstar" among the Warhol disciples after leaving the muse-dom of her former mentor, Salvador Dali. The surrealist icon introduced her to Warhol in 1963, kicking off what would be a decade long membership in one of the most influential art collectives in the history of the art world. During the years of her Factory career, she would abandon her baptismal name, Isabelle Collin Dufresne, and transform into the Bohemian star of dozens of Warhol's experimental films, known only by her pop moniker, Ultra Violet.

But since chronicling her unforgettable history, the artist has been adamant that she is a woman of the future, not the past. "Everyday I ask myself what should I do today, what should an artist in 2012 do today," she muses during our interview. In her post-Factory years, she has created a formidable body of her own art, working in both a New York space and a studio in her homecountry of France. In series like "Self-Portrait," "9-11," and "Angel and Michelangelo," the artist focuses on mostly spiritual themes represented through installations of light, glass, metal and spare computer parts. Her work though, dripping with neon color and American cultural references, has unmistakable echoes of her pop-filled past, emphasized by her decision to keep her Factory-era name and dress almost exclusively in the violet hue she so proudly donned in her former life.

With a constant eye toward tomorrow, Ultra Violet sat down with us to talk about these distant echoes. In honor of Warhol's birthday, she discussed her art career after the Factory, the spiritual impact of Warhol's legacy, and how she thinks Andy is the best American artist of the 20th century. (Scroll down for images.)

Ultra Violet's memoir, Famous For 15 Minutes

UV: So you are doing an article about Andy’s birthday?

HP: Yes, that’s what we are working on.

UV: It’s in August?

HP: Yes, August 6th.

UV: When I wrote my book, I wanted to have the exact date of birth of Andy. Because Andy used to say I was born here, I was born there, I was born on this date. I did a lot of research and it was very difficult to find a real birth certificate. The reason is, when he was born, his mother, who was quite an original, forgot to declare him as being a newborn baby. And when he went to school, I don’t know what age, maybe 10, he needed to get a scholarship and she needed a birth certificate. So she had to go to town hall or wherever with her sister and swear that this little boy was born on such and such date. And so therefore, his birth certificate was not where they normally are, and probably Andy knew about that. So I got the real certificate, which I published in my book, and subsequently the Varchola family called me and said, “Could we get a copy of the birth certificate?” which I gave them. So anyway, I have the exact date that he was born.

HP: Speaking of your memoir, in it you have a quote about the Factory that states, “The whole game is people: meeting them, getting them involved, asking them for money, pulling them into our orbit, being invited to their parties and events. Every new person is a new possibility, a link in an ever-lengthening chain, an ever-climbing ladder.”

UV: I said that in my book?

HP: Yes. So how did you play the game? Did anyone not play the game and succeed, in your mind?

UV: Well, everyone played the game. I mean, I wrote the book in 1988 I think, just when Warhol had died, and when I was much more lucid. But at the time in the ‘60s, we were just having fun. We did not know we were playing a game, we did not know about the strategy, but I am sure Andy knew all about it. But you know it was very different, it was a very hedonistic era. We were just having fun. But when you write the book, it’s just like a different story.

HP: When you began creating your own artwork after leaving the Factory, did you have a vision for where your career was headed?

UV: When Warhol died, that night I had a dream, and in the dream I was with Warhol and we were together in kind of an open cathedral with open seating and smoke and millions of objects. And then I remember Andy looking at objects and not knowing which ones to take. Then I remember in the dream telling him, “The shroud has no pocket,” and waking up. So then I was having breakfast in my kitchen, and I turned on the radio and I heard that Warhol had died. I thought that was very interesting and I took it as an omen that -- and maybe it sounds pretentious -- that I should carry on his mission.

And when I say his mission, are you familiar with his last work that he was doing before he died? Religious work. So they were Last Supper, Madonnas, words from the scripture, a punching bag with the face of Christ, and things like that. And a lot of my work is based on spiritual or religious things. I study the scripture and a lot of it is based on the book of Revelation, which has angles on every single page. And I used to paint angels -- I have some in the drawer, you see those work over there [points to her series of "Angel and Michelangelo" paintings of Mickey Mouse figures with wings] and below each of those is written Mickeyangelo, Mickeyangelo, and they have wings. It’s another way of expressing angels. And the over there [points to black and white photograph], it’s the "Last Supper", which was a video that I did in 1972 with 13 women. This was sort of my feminist era, which I am no longer. But I had a preoccupation with God and spirituality. Why is God a man? Why are the apostles a man? Why, why, why? What is the role of women?

So anyway, I think that Warhol’s legacy for his work is that he depicted the American dream and the reversal of the dream -- the disaster series. But his conclusion is not the dream nor the disaster, but it’s spiritual work. We are spiritual beings. and what matters most is where we come from and where we are going after this. And Warhol was raised very religious, and maybe he went away from that, but he was very intuitive and he told me, “If I go to the hospital, I won’t come out alive.” That’s exactly what happened. I think he knew the end was near. And so again, the two last years before he died, he was doing religious work, you might say, which I find very interesting.

Ultra Violet (center) with Salvador Dali

HP: You have incorporated some American iconography in series such as "Angel and Michelangelo," which is something else Warhol did. Is that another influence you try to intentionally bring out in your work?

UV: Well, those are older. I don’t know that I would do this today. This is a funny angel. I have painted some straight angels [points to a series of wings hanging on the wall]. But to tell you the truth, Mickey is a remarkable person or archetype. It’s the first animal that spoke with a human voice. Tell me who else spoke with a human voice. Nobody! Then he has those extraordinary, parabolic ears -- it’s a radar, it captures everything, knows everything. You can talk to him, he doesn’t criticize you, you approve of his smile, it makes you feel good. And whenever he turns his head right or left, you always have those parabolic radar looking at you. It’s an extraordinary graphic.

HP: Beyond your spiritual work, do you still feel influenced by Andy’s art or the art done by other Factory members?

UV: Well, the other members of the Factory, the majority are dead. So I could be inspired by their death, but I move on. My speciality is to move on and to change. But I am very grateful to have met Warhol and learned from him. He was extremely intuitive and he was a genius of sorts. And I think he put me on the map. I mean, I don’t know what Ultra Violet is worth, but without Andy there would be no Ultra Violet, so I am grateful.

HP: The very name Ultra Violet, which you still use, originated during your time with Andy, right?

UV: When I met Andy, he said, “You have to change your name.” Everybody there took a pop name. My birth name is Isabelle Collin Dufresne. You can imagine in this American culture, they can’t spell it, they can’t pronounce it. So I had to change my name. And I was reading an article on light in Scientific American, my favorite magazine then, and I saw the words Ultra Violet -- just to tell you, my preoccupation with light was then and is still now. And I have a lot of light work. To me, light is the spirit.

HP: The Factory was such a collaborative environment, open to a number of artists like yourself. Do you see anything like that existing in the art world today?

UV: Not as much, because Warhol was very clever. He had the idea to have that loft, to make it silver like it was a giant reflective mirror, and the door was always open. My door is usually locked now [laughs]. In the ‘60s, it was all “make love not war.” There was a very communal idea in the air. I don’t think it’s the same today. And art then was such a -- I don’t want to say novelty, but...I don’t know. Today, because of the global era and the Internet, there are a billion artists. You just cannot know them all and it’s much more diversified than it was then. New York was really the center of the art world, today maybe it is questionable. So at the time, he had the genius to have the Factory, every other artist could have had a factory but did not. Just the fact to call it “Factory,” though it was an ex-factory, it was a place where we manufactured people, art, movies, paintings, you name it. So that was a very a unique moment in time and in history, no doubt.

HP: Do you still prefer to make art in New York or abroad?

UV: I like New York much better. I like the American spirit, and I don’t know if you’ve ever been in Nice [the location of her other studio], it’s lovely but there is nothing to do in Nice. I like action. You interview me about the past, and it’s ok, but I am interested in tomorrow. What am I doing tomorrow. I don’t live in the past. And I think that America is still the land of opportunity and belief and faith, and that opens the door. When you believe, it’s possible. When you don’t believe, nothing is possible. So I absolutely love this country.

And this is why I did so much work on 9-11. Because being an American, being in New York and being an artist, I had to do something about 9-11. The question was what, and the answer was not simple. Because it was a very solid event that I don’t think we have yet recovered from it. And I did not want to offend anyone, especially the families, the memory, and I think I just came to the conclusion that this is just the marking of time. A date, and I think that no one can object to it. The color [points to the violet "9-11" sculpture series] is the color of morning in Europe on Easter. They cover everything in that sort of purple-magenta. And it’s also my signature; I used to sign a painting with Roman numerals. But when I realized that 9-11 is two “I” and two “X,” it was, design-wise, very fascinating. And it’s a palindrome. So I just felt a responsibility, if you wish, in relation to 9-11.

Ultra Violet's studio in Chelsea.

HP: Do you see any young artists today whose work has reverberations of Warhol's style or embodies the spirit you discussed of the 1960s?

UV: Young artists? No. Does he have to be young? One comes to mind, though he is not young, he is German. Anselm Keifer. He’s an extremely good artist and his work is meaningful, moving, original. It has reference to history. So I like his work a lot. There are a lot of others, but I cannot tell you. I work. I do not go out to shows. The people that go out to every opening are people who don’t work. It’s really a distraction.

HP: Where do you see your career taking you in this next year?

UV: Hopefully somewhere! [Laughs] I recently came back from the fair in the Hamptons, and the reaction was extraordinary. Sometimes people laugh, and I like that, because art is so serious. And to make people laugh in Chelsea, that is quite a masterpiece.

I think that I am empowering people with their self-portrait. I think everyone needs an iPhone, everyone probably needs an Apple, and [everyone] needs a self-portrait. Everybody needs to be famous for 15 minutes. And everybody already is famous for 15 minutes. And I am trying to go for 16 minutes. And that is very hard.

HP: And the title of your book speaks to this: "Famous For 15 Minutes." What drove you to choose this phrase?

UV: Oh, because it’s a phenomenal phrase. Which I coined, and then Warhol used, and now the whole world is using it! You hear President Obama use it, everybody uses it. It has become a classic phrase, because today, everyone is famous or can be famous for 15 minutes.

HP: One last question. When we contacted you to do this interview commemorating Andy Warhol’s birthday, what was your reaction to still being connected with him and the Factory?

UV: Oh, yeah, it’s very nice that he is being remembered. You know, Andy Warhol has the largest, single-artist museum in the United States. He has a foundation here, so you know, I think his legacy is immense. And I think he is maybe the best American artist of the 20th century, so I think it is well deserved. And I was very privileged, I guess, to have met him and to have understood who he was. It was a great blessing. But I am a futuristic woman, I usually don’t like to talk about the past. I am interested in tomorrow, more than yesterday. Otherwise I would have no future. And I work at my future. People tell me all the time that I have a great past, and I tell them I hope I have a great future!

After the interview ended and we made our way to the door, Ultra Violet told us to tell Andy "Happy Birthday" for her. See a slideshow of the pop art master below, and let us know your thoughts in the comments section.