On the afternoon of June 25, 1876, on high bluffs above the Little Big Horn River, Col. George Armstrong Custer halted the 7th Cavalry and dictated an order. "Benteen. Come On. Big Village. Be Quick. Bring Packs. P.S. Bring Packs."

The order was scribbled and handed to trumpeter John Martin, who grabbed it and galloped off in the direction of Captain Benteen and the left battalion of Custer's command. As he rode away, the trumpeter turned in his saddle for one last glimpse of the 7th Cavalry. The blue-coated soldiers were galloping down into a ravine, flags flying, the gallant Custer, dressed in buckskins, leading the way.

In less than two hours, Custer and all 210 men of his command were dead.

What happened in those two hours is one of the great mysteries of history. None of the cavalrymen survived. Accounts by the Sioux and Cheyenne warriors who wiped them out were confusing or contradictory. Many Indians, fearing retaliation, told the whites what they wanted to hear. Others related what they saw, but their story was not believed.

And so, in place of fact, a legend developed. According to the myth, a courageous, but perhaps rash, Colonel Custer underestimated Indian strength and attacked overwhelming numbers of painted warriors who were camped on the Little Big Horn.

Surrounded, betrayed by his subordinates, captains Reno and Benteen, who failed to come to his aid, Custer had no choice but to gather his men on what came to be called Last Stand Hill. Here, fighting back to back, his soldiers realized they were doomed, but they were determined to sell their lives dearly. Custer, with his long golden hair flowing and two blazing pistols, stood beside the flag and fought to the last bullet.

It was this romantic version of Custer's Last Stand that became the basis for hundreds of paintings, films and books.

Unfortunately, very little of it appears to be true.

Today, a visitor to Southern Montana's Little Big Horn Battlefield National Monument can learn what historians, archeologists and scientists think really happened on that afternoon in 1876. Using metal detectors, microscopes and CSI techniques, they were able to study thousands of rifle cartridges and bullets discovered on the battlefield. Because each rifle cartridge has a distinctive mark from a firing pin, they were able to trace where each gun was fired, and therefore, where each soldier fought and how well they fought. Coupled with new interpretations of Native American accounts, this has helped historians piece together the ebb and flow of the battle and write a much different view of what may actually have happened.

A Unique Battlefield

The high bluffs along the Little Big Horn River are rolling grasslands with unending views across what Montana calls "Big Sky Country." Even without the history, this would be a wonderful place to stop and appreciate the beauty of the countryside. But once you know what happened here, this becomes haunted and hallowed ground. The museum at the entrance to the national monument is a good place to begin your introduction.

The Little Big Horn Battlefield is unique in the world in that there is a macabre marble marker indicating where every single soldier was killed. Two days after the battle, when the relief force finally arrived, they found a gruesome and dreadful sight. Scattered over a wide area on several hills, were all 210 of Custer's men... each man lying in the sun, scalped, stripped naked and often mutilated. One victim had 105 arrows stuck in him.

Shocked, the relief force buried every soldier exactly where they had fallen and marked the spot with a wood cross. These were later replaced in 1890 with marble markers, and all the bodies were eventually interned in a single grave under a large monument. What was believed to be Custer's remains were removed and buried at West Point.

But these first elementary markers allowed historians to know where every single soldier had been killed in the battle. The lingering question was, how did they get there and why were they scattered in so many places?

Exhibits in the museum set the stage for the battle.

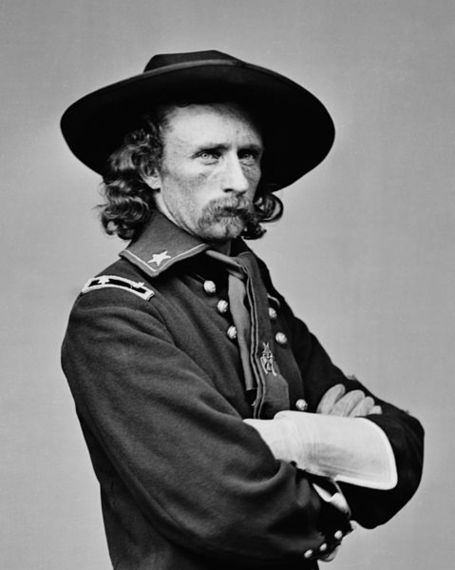

In 1876, several centuries of conflict between Indian and Euro-American cultures were coming to a finish. Both whites and Indians had repeatedly broke treaties. Frustrated and seeing their way of life threatened, Indian leaders including Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse moved a large band of 7,000-8,000 Lakota Sioux and Northern Cheyenne off the reservation and into the buffalo-rich country of southeastern Montana. In response, the U.S. government ordered the cavalry to round them up and move them back. Leading one of the attacking forces was the youngest general to come out of the Civil War, the flamboyant, dashing and immensely popular, George A. Custer.

Strategic thinking held that the way to round up Indians was to capture the women and children and hold the noncombatants as hostages. Indian villages, if threatened by cavalry, would break up into small groups and scatter like the wind. Capture the women, children and elders, and the warriors would be reluctant to counterattack and forced to surrender. Of course, this could result in large numbers of women and children being killed, but that did not deter the U.S. army.

So Custer's main concern on June 25 was not fighting a battle, but rather locating and surrounding the Indian camp before they could separate and flee. However, his planned changed when some Indians discovered the 7th Cavalry first.

Afraid that the Indians, now warned, would disperse, the always-aggressive Custer went on the offensive. He divided the 7th into three battalions. Captain Benteen was ordered to search the west side of the Little Big Horn, while Custer and Reno took the main body north along the river. In a few miles, Custer came upon the large Indian camp he was seeking, and although his men were exhausted, the battle was underway.

Custer ordered Reno to attack the camp from the south with one battalion, while he circled around the ridge with the other battalion and hit the Indian village from the north. Based on all previous Indian-soldier encounters, this was a risky, but workable strategy. However, things went awry from the start.

Reno's charge faltered. Instead of attacking straight into the village, Reno halted 200 yards away and formed a skirmish line. And with good reason. Custer's intelligence had estimated a village with 800 warriors, but there were, in fact, as many as 2,000 fighting men. Even with surprise on his side, Reno's 140 men were outmatched and soon forced on the defensive.

At a crucial moment of the firefight, a friendly Crow Indian scout standing next to Reno was shot in the head, splattering Reno with brains and blood. Reno, understandably, appears to have become disoriented. He ordered a retreat that soon became a panicked rout. By the time his command got to a safer position, 40 of his men were dead. Shortly later, Benteen arrived on the scene. With Indians still attacking, Reno shattered, and his battalion in chaos, Benteen elected to stay put and help Reno's men. Custer was now on his own.

Custer's Last Battle

Historians can never be certain, but based on archeological evidence, this is what they think happened. Unaware of the outcome of Reno's attack, Custer remained on the offensive and rode north to attack the village from its upper reaches. However, by the time he got there, the women and children had fled. Still aggressive, Custer divided his force into two wings. The right wing held what came to be called Calhoun Hill and waited here for Benteen, who they assumed would be on his way. Custer led the left wing in search of a new ford further north from which he could still capture the noncombatants.

From archeological evidence, we know the right wing formed a skirmish line. Tactics of the time called for men to stand five yards apart in a line, and archeologists found shell casings consistent with a defensive line. But as more and more Indians left the Reno fight and turned their attention to Custer's men, the pressure on the right wing intensified. Men in battle who become fearful tend to bunch together and the shell casings indicate the men on the ridge fell back and this "bunching" started to occur.

If the pressure of an attack becomes too intense, it can lead to panic. Men in panic seldom fight back. They might even throw away their guns, as they run to what they perceive will be a safer place. This is apparently what happened to the right wing. Overwhelmed by superior numbers of Indians, the soldiers gave way to panic and fled. Indian accounts of the battle spoke of the soldiers acting like they were drunk, running like a buffalo stampede, throwing away their guns and crying like babies.

The Custer legend interpretation depicted the soldiers in this part of the battle bravely fighting a retreat back to Last Stand Hill. The lack of gun casings in the area and the high number of marble markers leads archeologists to a new depiction -- that of panicked soldiers fleeing and being shot down as they ran. As you stand on Calhoun hill and see the white marble markers stretching out across the grassy slopes, each indicating the spot where a soldier fell, you can feel those awful moments and get a sense of the terror the men must have felt.

Custer, meanwhile, had found his river crossing, but he had too few men to capture the village. Still confident, he turned back to collect the rest of his troops (and hopefully Benteen's battalion) and arrived at a viewpoint in time to see the horrifying collapse of the right wing. Custer with just 85 men raced to Last Stand Hill to offer support. Only 20 men from the right wing survived to join him. Now, with half his men dead, surrounded, in dust and confusion, Custer would have realized for the first time he was no longer on the offensive, and was instead, cut off.

The end came swiftly. Rather than the fight to the last bullet often depicted, nine men tried to escape by horseback heading south, but were cut down. Another 45 tried to break out towards the river or hide in a ravine, but they too were sought out and killed. Custer, flanked by his two loyal brothers, a beloved nephew and some 50 other troopers, was quickly overrun. From shell casings, we know the battle at the end lasted just minutes -- not the long protracted battle of films.

Who was to blame?

The easiest answer is that Custer didn't lose so much as the Indians won. They had vastly superior numbers, they were fighting for their homes and families and were brilliantly led by chiefs Crazy Horse, Lame White Man and Gall.

Certainly, Custer was let down by Reno, who did not press his charge on the village, and by Benteen, who did not "come on," as ordered, to his support. Had Reno and Benteen come forward. they might have suffered the same fate as Custer. However, under the strict guidelines of the 19th Century army, they must take some blame for not following orders, even if those orders led to disaster, and history has been harsh in its judgment of them.

As it has been on Custer. Custer divided his force in the face of uncertain numbers, fought on ground he did not know, and as commander, bears the ultimate responsibility. Throughout the Civil War, he fought a dozen battles in similar circumstance and always came out on top. At Little Big Horn, his luck ran out.

As it did for the Indians. Though victorious here, within three years, they were defeated and forced back to the reservation. Both Crazy Horse and Sitting Bull were murdered in unusual circumstances by white and Indian guards. Little Big Horn proved to be the high point... and the beginning of the end for the free Plains Indians. Within a few years, everything changed for everyone who fought at Little Big Horn. Only the battleground remained the same. It is, and always will be, a strange and haunted place.

IF YOU GO:

Little Big Horn Battlefield

CORRECTION: This post previously misstated the date of Custer's Last Stand as June 26, 1876. Custer was killed on June 25, 1876.