This six-part series originally ran on the Huffington Post between May 13 and 24, 2013. Below are all six parts in consecutive order.

Part 1: A Glaring Lapse in Climate and Energy Coverage

One of my morning rituals is half-listening to NPR's "Morning Edition" while I'm getting ready for work. But on January 3, when a story came on about the fate of the wind industry's production tax credit, I snapped to attention. It was good news. Congress's eleventh hour "fiscal cliff" agreement had left the tax credit in place for at least one more year.

The NPR story featured a spokesman for a small Iowa wind project who explained how the tax credit benefits rural communities. For balance, it also included a naysayer: Thomas Pyle from the American Energy Alliance, who wanted Congress to kill the subsidy.

"It's not that the subsidies for the wind industry in and of themselves are bad, but it is part-and-parcel of a larger problem, and that is, is that the federal government is notoriously bad at energy policy," Pyle said. "They have been for decades, and we think it's time for them to step aside."

But who is Thomas Pyle and what is the American Energy Alliance? The story didn't say.

It turns out that the American Energy Alliance is a front group for the oil and gas industry. Pyle, AEA's president, is a former lobbyist for the National Petrochemical and Refiners Association and Koch Industries, the Wichita, Kansas-based coal, oil and gas conglomerate owned by the billionaire brothers Charles G. and David H. Koch (pronounced "coke"). Koch Industries is the second largest privately held company in the country.

Digging a little deeper, I learned that AEA is the political arm of the Institute for Energy Research, where Pyle also serves as president. From 2006 to 2010, IRE received hundreds of thousands of dollars from the oil and gas industry's trade association, the American Petroleum Institute; ExxonMobil; and the Claude R. Lambe Charitable Foundation, a philanthropy controlled by Charles Koch.

OK, but didn't Pyle say the federal government should stop subsidizing all energy? That sounds pretty evenhanded, right? In fact, as aggressive as Pyle and his benefactors are about undermining their competition, they are even more vehement about protecting themselves--and they know full well their friends in Congress wouldn't dare touch oil and gas subsidies. Indeed, legislation introduced last May to pull the plug on the billions in annual tax breaks and subsidies the oil, gas and coal industries enjoy died a quick death.

Obviously there wasn't enough time to explain all that in a four-minute news segment. But at the very least the reporter should have identified Pyle as an oil and gas industry spokesman. I emailed the reporter later that day to point that out. I got no response.

Why Don't Reporters Follow the Money?

Twenty-five years after NASA scientist James Hansen testified at a Senate hearing that scientists know with a 99 percent certainty that burning fossil fuels--not natural climate variations--is warming the planet, there are many reasons why Congress has yet to take significant steps to curb U.S. carbon emissions. The hundreds of millions of dollars oil, coal, auto and manufacturing industries have donated to federal candidates is certainly a factor. So are the hundreds of millions of dollars they've spent to lobby them once they're elected.

But the news media are also to blame. Too often they have provided a platform for fossil fuel industry-funded think tanks and advocacy groups to make spurious claims about global warming and renewable energy and allowed them to pass themselves off as independent, disinterested parties promoting free markets and limited government.

Over the years, journalists have consistently relied on these groups to provide the "other side" in climate and energy stories when, in fact, there is no other side--at least not on the science or the fact that we have to wean ourselves off fossil fuels to avoid some of the worst consequences of climate change. All too often, however, the news media have presented these two sides as equivalent, despite the fact that one rests its argument on peer-reviewed climate science while the other promotes the distortions of industry-funded contrarians, most of whom are not climate scientists--or even scientists at all.

NPR's ombudsman addressed this deficiency two years ago. "NPR often does a lousy job of identifying the background of think tanks or other groups when quoting their experts," Alicia C. Shepard wrote in an essay posted on the network's website in April 2011, just a month before her three-year tenure ended. "NPR also rarely explains why listeners should pay attention to the experts it chooses to quote. This matters."

Shepard was right. It does matter. But her solution of just tacking on "libertarian," "conservative" or "liberal" labels doesn't sufficiently inform the public whose interests these think tanks are serving. In any case, her message apparently fell on deaf ears. The glaring omission in the January 3 story is still more the rule than the exception at NPR, and the network is not alone. Most, if not all, mainstream news organizations are guilty of the same transgression.

To gauge just how widespread this failure is, I recently looked to see if elite news organizations reported funding sources for eight prominent climate contrarian groups in climate and energy stories that ran from January 2011 through December 2012. The groups--which I have dubbed the "Oil Eight"--are the American Enterprise Institute, Americans for Prosperity, Cato Institute, Competitive Enterprise Institute, Heartland Institute, Heritage Foundation, Institute for Energy Research (and its political arm, American Energy Alliance), and Manhattan Institute for Policy Research. When it comes to climate, the Oil Eight share the same goals as their corporate underwriters: sow doubt about the reality or seriousness of global warming, stifle government efforts to curb carbon emissions, and hinder the growth of renewable energy technologies.

Who are their corporate underwriters? From 2001 through 2011, the Oil Eight collectively received more than $23 million from one or more of the following interested parties: the American Petroleum Institute, ExxonMobil, General Motors and three Koch family foundations: the Charles G. Koch Charitable Foundation (now the Charles Koch Foundation), David H. Koch Charitable Foundation and Claude R. Lambe Charitable Foundation, according to data I gleaned from federal tax filings, the Foundation Center and the Bridge Project's Conservative Transparency database. In addition, another Charles Koch philanthropy, the relatively unknown Knowledge and Progress Fund, contributed nearly $8 million from 2005 to 2011 to a secretive, pass-through foundation called Donors Trust. From 2001 through 2011, Donors Trust and its affiliate Donors Capital Fund laundered more than $54 million of largely untraceable contributions to the Oil Eight, far outpacing ExxonMobil and the three main Koch family foundations.

Using the Nexis database and the news organizations' archives, I tracked coverage by the Associated Press, NPR, the political trade journal Politico, and six leading newspapers: the Los Angeles Times, New York Times, USA Today, Washington Post and Wall Street Journal. I confined my search to stories on climate and energy, so I excluded pieces that focused on industry funding without mentioning either topic.

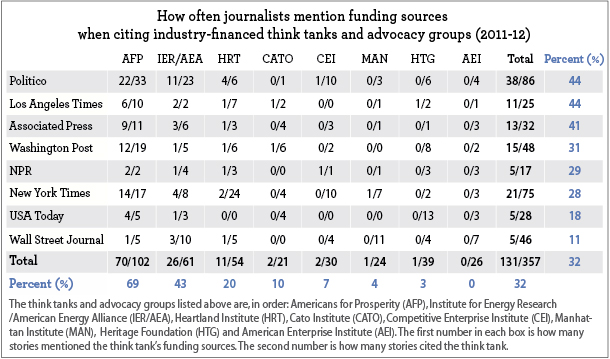

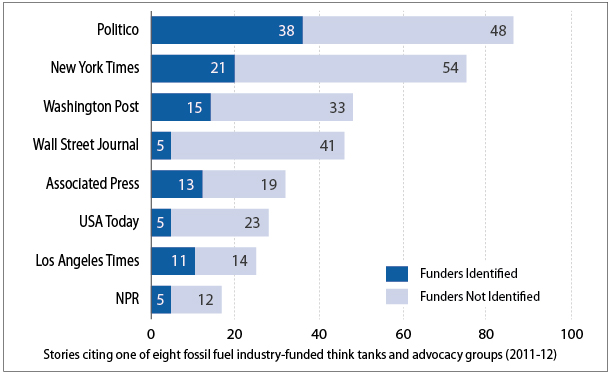

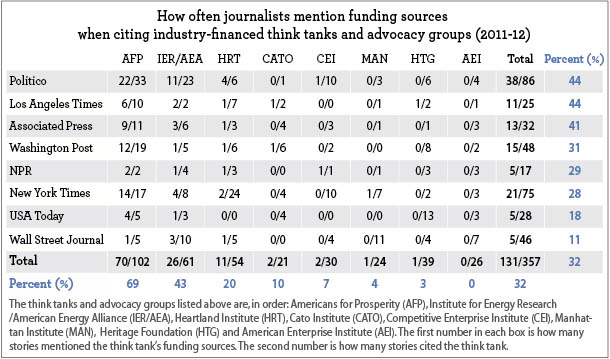

After poring over more than 1,000 stories, editorials, opinion columns and interviews, I narrowed my sample to 357 relevant pieces. Here's what I found: These top news organizations provided information about the Oil Eight's fossil fuel industry funding in only 32 percent of the climate and energy stories they published or aired over the two-year period.

When I was in school, 32 percent was an F.

The eight news organizations did the best job identifying the fact that the Koch brothers underwrite Americans for Prosperity, citing the Kochs as the group's funders 69 percent of the time. They were not nearly as attentive with the other groups, however. They disclosed the funders behind the Institute for Energy Research and its political arm, American Energy Alliance, in 43 percent of the stories that mentioned them in 2011 and 2012, and then their attention really faded. They mentioned the Heartland Institute's benefactors only 20 percent of the time, the Cato Institute's funders only 10 percent of the time, and the supporters of the remaining four groups--the Competitive Enterprise Institute, Manhattan Institute, Heritage Foundation and American Enterprise Institute--less than 10 percent of the time. (See the table at the top of this blog for my complete survey results.)

Politico ran the most climate and energy stories citing the Oil Eight during the two year period--86--and named their funders in 44 percent of its stories, tying it with the Los Angeles Times for the best record. The Los Angeles Times--which the Koch brothers would like to buy--ran 25 stories citing one or more of the Oil Eight, mentioning funders in 11 of them.

The news organizations that did the worst job identifying fossil fuel industry funders were USA Today, which cited them in only 18 percent of its 28 stories and op-eds, and the Wall Street Journal, which named them in only 11 percent of its 46 stories, columns and op-eds. That's very discouraging, given the two papers have the largest circulations in the country. #

Elliott Negin, the director of news and commentary at the Union of Concerned Scientists, is a former NPR news editor and managing editor of American Journalism Review.

Part 2: Disinformation Laundering at the Competitive Enterprise Institute

Social scientists use the term "information laundering" to describe the phenomenon of corporations funding seemingly independent think tanks to convey their message. A more accurate term would be "disinformation laundering." To be sure, it's just one of a number of tactics corporations and trade associations use to protect their interests, including supporting candidates and political parties, lobbying legislators, financing public relations campaigns, and underwriting university-based institutes. But backing anti-regulation think tanks enables corporations to disseminate their message anonymously--and more effectively. After all, a "scholar" with an "independent" think tank has more credibility than a corporation with the general public and, more important, with policymakers and the news media.

To understand just how the fossil fuel industry has been laundering climate disinformation, there are few better places to start than with the Washington, D.C.-based Competitive Enterprise Institute. CEI is the same think tank that notoriously reassured Americans that global warming is nothing to worry about in a TV commercial extolling the virtues of carbon dioxide. The spot's unforgettable tag line: "They call it pollution. We call it life."

During the 1990s, CEI and other think tanks that would later form the backbone of the climate contrarian movement received millions of dollars from tobacco and drug companies to attack the Food and Drug Administration's regulatory authority. The tobacco industry wanted to block efforts to address secondhand smoke, regulate tobacco as a drug, and curb cigarette advertising and sales to minors. The pharmaceutical industry, meanwhile, wanted to pressure the agency to speed up the drug approval process. CEI--which had no scientists, physicians or public health experts on its staff--went even further, calling on Congress to allow companies to market unapproved drugs and medical devices as long as they came with a warning that the FDA did not evaluate them for safety or effectiveness.

At the same time CEI and other think tanks--including the American Enterprise Institute, Cato Institute and Heritage Foundation--were laundering disinformation for the tobacco and drug industries, a coalition of 50 U.S. companies and trade groups was doing its best to discredit climate science and stymie national and international efforts to address global warming. Formed in 1989--just a year before the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) published its "First Assessment Report"--the Global Climate Coalition included the oil industry's trade association, the American Petroleum Institute; oil giants British Petroleum, Chevron, Exxon, Mobil, Shell and Texaco; and the Big Three automakers, DaimlerChrysler, Ford and General Motors.

The fact that the Global Climate Coalition represented major carbon polluters was no secret. For example, 42 of the 43 stories the New York Times ran citing the coalition between 1989 and 2002--the year it disbanded--noted that it was an industry lobby group and many of them connected it directly to oil, coal and electric utility companies. Over the same time period, the Washington Post linked the coalition to industry in all of the 41 stories it ran and, like the Times, periodically mentioned its ties to oil and coal companies.

By the late 1990s, however, key Global Climate Coalition members began enlisting the help of CEI and other tobacco industry-funded think tanks, which hid their involvement and made their arguments seem more credible. For example, between 1997 and 1999, British Petroleum, Daimler Chrysler, Ford, General Motors, Shell and Texaco collectively gave CEI $342,000. In 2001 and 2002, ExxonMobil donated $545,000, while two of the three main Koch family funds--the David H. Koch Charitable Foundation and Claude R. Lambe Charitable Foundation--kicked in $100,000 and $29,460 respectively. Given CEI's entire budget in 2002 was about $3 million, these grants were significant.

The ploy paid immediate dividends. Contrast how the New York Times and Washington Post identified the Global Climate Coalition with how they identified CEI, which quickly became one of the most-quoted climate change contrarian groups.

While the Times nearly always identified the coalition properly, only one of 12 climate and energy stories the paper ran from 1997 through 2002 citing CEI mentioned its industry connection, and that article merely stated it was "a pro-business research and advocacy group." Among other unhelpful labels, the other 11 stories called CEI a "conservative group," a "private group that opposes regulatory approaches to environmental problems," and "a public policy group that promotes free enterprise and limited government."

The Post did an equally abysmal job. Ten of 11 stories published from 1998 through 2002 called CEI either a "conservative" or "free market" think tank or didn't identify it at all. Like the Times, the paper's lone piece alluding to the group's corporate connection, an August 1999 op-ed, just called it a "pro-industry group."

Journalists Continue to Enable CEI to Mislead the Public

Today, the news media continue to give CEI and other fossil fuel industry-funded think tanks too many opportunities to deceive the public. To try to get a fix on how often this happens, I reviewed two years' worth of climate and energy pieces published or aired by eight elite news organizations: the Associated Press, NPR, the political trade journal Politico, and six leading newspapers: the Los Angeles Times, New York Times, USA Today, Washington Post and Wall Street Journal. I confined my search to stories on climate and energy, so I excluded pieces that focused on industry funding without mentioning either topic.

Using the Nexis database and the news organizations' archives to search for stories, editorials, opinion pieces and interviews, I looked at how these media outlets described CEI and seven other prominent fossil fuel industry-funded groups I call the "Oil Eight."

How did they do?

Overall, the news organizations identified funding sources in 32 percent of the relevant stories that ran from January 2011 through December 2012. But their track record describing CEI was decidedly worse. Only two of 30 climate and energy stories citing CEI over that time period mentioned that fossil fuel interests fund it. In other words, my eight top news organizations failed to note that CEI is a fossil fuel industry-backed group more than 90 percent of the time. (For more survey results, click here.)

Just one energy story in Politico, which ran 10 articles mentioning CEI, reported that the think tank gets fossil fuel industry money. The only other time CEI's funding was mentioned was during an interview NPR Fresh Air host Terry Gross did with New Yorker staff writer Steve Coll, who was promoting his new book on ExxonMobil.

What makes this omission so puzzling is journalists should be well aware of the connection. New York Times reporter Jennifer 8. Lee first reported that CEI was one of ExxonMobil's grantees back in 2003. That makes it especially surprising that the Times, in particular, did such a poor job. Not one of the 10 climate and energy stories the national newspaper of record published in 2011 and 2012 mentioning CEI cited its link to fossil fuel interests.

One of Washington's "Most Prominent Skeptics" Gets a Free Ride

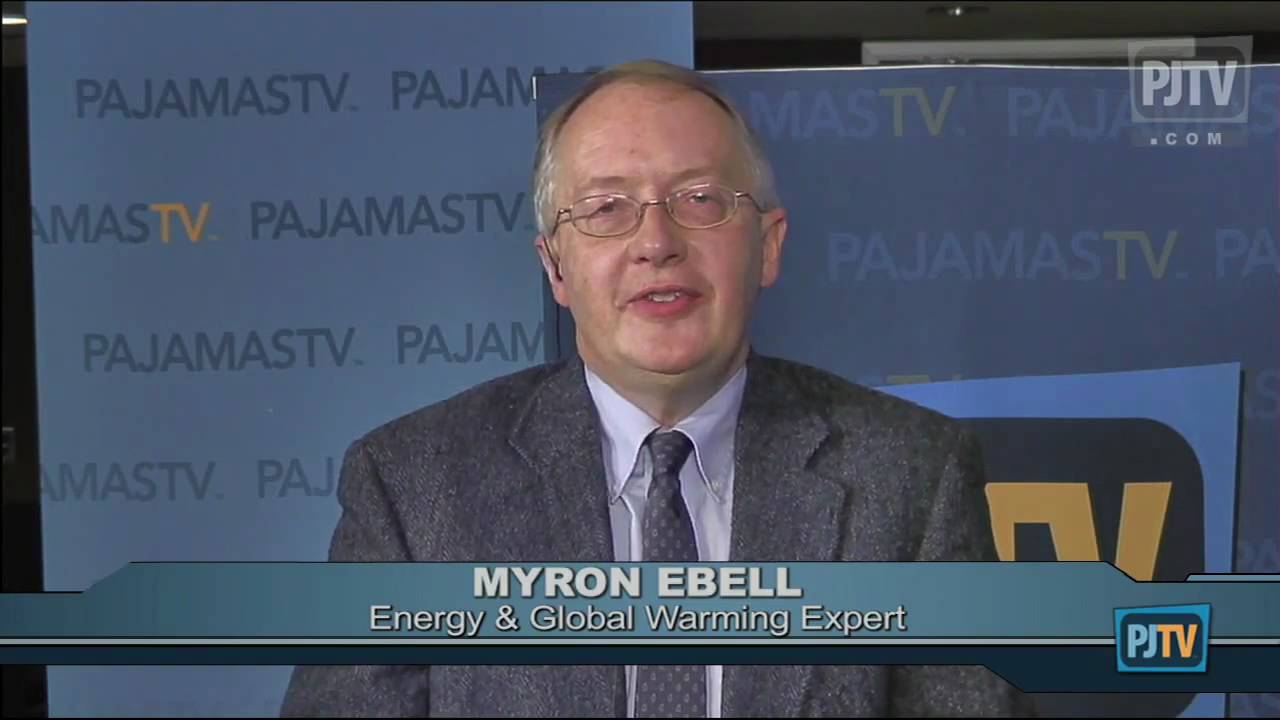

The way the New York Times and Associated Press described CEI and its main spokesman on climate, Myron Ebell, in two stories last year illustrates how the news organizations in my survey fell down on the job.

Before joining CEI in 1999, Ebell was the policy director at the Exxon-, tobacco industry-funded Frontiers of Freedom, a property rights, anti-environment organization started by former Sen. Malcolm Wallop (R-Wyo.). While still at Wallop's group, Ebell moonlighted as a member of the American Petroleum Institute’s Global Climate Science Team, a small task force API formed in 1998--when API members Exxon and Mobil announced their merger--to develop a strategy to discredit climate science that mimicked the tobacco industry's anti-FDA campaign.

The same year API formed the task force, Exxon started cutting checks to CEI. From 1998 through 2005, the company—which officially became ExxonMobil in 1999—gave CEI more than $2 million. Over the last decade, the think tank also received $25,000 from API (2009), $245,000 from General Motors (2003-08), $24,100 from the Charles G. Koch Charitable Foundation (2009), and $222,620 from Charles Koch's Claude R. Lambe Charitable Foundation (2002-11).

Ebell, the director of CEI's Center for Energy and the Environment, is not a scientist. He has a master's degree in political theory from the London School of Economics and Political Science. But that doesn't stop him from posing as a climate expert--and it hasn't stopped journalists from quoting him. His standing in the global warming debate prompted Vanity Fair to publish an unflattering profile of him in May 2007 highlighting his ExxonMobil funding, while the Financial Times in March 2010 named Ebell "one of the most prominent skeptics in Washington."

In March 2012, New York Times environment reporter Justin Gillis called Ebell for his opinion of two peer-reviewed studies on global warming-induced sea level rise that ran in the journal Environmental Research Letters. The studies estimated that 3.7 million Americans are at risk from coastal flooding due to rising sea levels, and one of the authors told Gillis, "We have a closing window of time to prevent the worst by preparing for higher seas."

Gillis set up a quote from Ebell in his March 14 story this way:

The handful of climate researchers who question the scientific consensus about global warming do not deny that the ocean is rising. But they often assert that the rise is a result of natural climate variability, they dispute that the pace is likely to accelerate, and they say society will be able to adjust to a continuing slow rise.

Myron Ebell, a climate change skeptic at the Competitive Enterprise Institute, a Washington research group, said that "as a society, we could waste a fair amount of money on preparing for sea level rise if we put our faith in models that have no forecasting ability."

Times readers likely would conclude that Ebell is one of a "handful of climate researchers" who has doubts, especially since Gillis called CEI a "research group." In fact, neither Ebell nor CEI conduct any scientific research, none of CEI's energy and environment program staff members are scientists, and Ebell's criticism of climate models doesn't square with reality. A peer-reviewed paper published recently in the journal Nature Geoscience found that climate models accurately predicted the rise in global temperatures over the last 15 years to within a few hundredths of a degree.

A few months later, Associated Press science reporter Seth Borenstein turned to Ebell for comment for a May 31, 2012, story, "Warming gas levels hit 'troubling milestone.'" The article reported that Arctic monitoring stations were detecting more than 400 parts per million of carbon in the atmosphere.

"These milestones are always worth noting," Ebell told Borenstein, but he insisted that average global temperatures haven't gone up since 1998, despite higher carbon concentrations. "As carbon dioxide levels have continued to increase," Ebell said, "global temperatures flattened out, contrary to the [climate] models."

Borenstein mistakenly called Ebell an economist, merely described CEI as "conservative," and made no mention of the think tank's funders. But he did refute Ebell's statement. "Temperature records contradict that claim," he wrote. "Both 2005 and 2010 were warmer than 1998, and the entire decade of 2000 to 2009 was the warmest on record, according to NOAA [the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration]."

If Borenstein also had reported that CEI is backed by the fossil fuel industry, it would have helped explain Ebell's motivation for mangling the facts. #

Elliott Negin, the director of news and commentary at the Union of Concerned Scientists, is a former NPR editor and managing editor of American Journalism Review.

ExxonMobil Chairman, President and CEO Rex Tillerson may sound more reasonable than his predecessor, but he's still funding climate contrarian think tanks. (Getty Images)

Part 3: Public Interest Groups Exxpose Exxon--Temporarily

Until just a few years ago, ExxonMobil was without a doubt the Daddy Warbucks of climate contrarian philanthropy. While most oil and auto companies stopped funding contrarians by the time the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) issued its 2001 "Third Assessment Report" underscoring the severity of the global warming threat, ExxonMobil opened the spigot.

The oil giant's behind-the-scenes role in underwriting contrarian think tanks, however, went largely unnoticed. When journalists cited these think tanks, they most often labeled them "conservative," "libertarian" or "free market" if they defined them at all, and--more important--they consistently failed to explain that these seemingly independent groups were in essence acting as PR agents for ExxonMobil in particular and the fossil fuel industry writ large.

It took a nudge from public interest groups to get the mainstream press to take a closer look. Although one of the first articles on ExxonMobil's role appeared in the New York Times back in May 2003, it was a one-off story. The paper didn't mention the company's funding agenda again until July 2005 when a coalition of a dozen groups launched the Exxpose Exxon campaign to protest the company's attacks on climate science and its support for drilling in Alaska's Arctic National Wildlife Reserve.

Two years later, a January 2007 report by an Exxpose Exxon coalition member, the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS), pushed the company further into the media spotlight. "Smoke, Mirrors and Hot Air: How ExxonMobil Uses Big Tobacco's Tactics to Manufacture Uncertainty on Climate Science" revealed that between 1998 and 2005, the oil giant had lavished $16 million on a network of more than 40 anti-regulation think tanks to launder its message. Many of the company's grantees, which together function as a climate disinformation "echo chamber," were veterans of the tobacco industry's war against tighter government regulation in the mid-1990s.

Widely covered by wire services, television networks and leading newspapers, the UCS report drew blood. A week after its release, Rex Tillerson, who took over as ExxonMobil's CEO just a year before, conceded that his company had a PR problem. "We recognize that we need to soften our public image," he said, according to a January 10 story in Greenwire, a trade publication. "It is something we are working on."

A month later, just after the release of the IPCC's "Fourth Assessment Report," the company made what appeared to be an about-face. "There is no question that human activity is the source of carbon dioxide emissions," said Kenneth Cohen, ExxonMobil's vice president of public affairs, as reported by Greenwire on February 9. "The appropriate debate isn't on whether climate is changing, but rather should be on what we should be doing about it." But what about the ExxonMobil grantees UCS identified in its report? Cohen told Greenwire that the company had stopped funding them.

Well, not quite.

It is true that ExxonMobil's annual payout to contrarian groups peaked at $3.48 million in 2005 and the company began to drop grantees. That year the company severed ties with the Competitive Enterprise Institute, and over the next two years it cut off a number of others, including the Cato Institute, Frontiers of Freedom, George C. Marshall Institute, Heartland Institute and Institute for Energy Research.

That said, ExxonMobil's contrarian funding dipped only 25 percent after Tillerson took over in 2006. It spent $16 million from 1998 through 2005--an average of $2 million a year--and $8.83 million from 2006 through 2011--an average of $1.47 million a year. In 2011, the company doled out $1.08 million to 17 contrarian groups, including seven named in the 2007 UCS report.

Journalists Continue to Ignore the Money Behind Climate Contrarians

Despite the fact that ExxonMobil is still a significant contrarian funder, the flurry of media interest in the company's funding agenda sparked by UCS's exposé died down soon after its release and remains feeble to this day. What happened?

First, ExxonMobil's new CEO, Rex Tillerson, sounded a lot more reasonable than his predecessor Lee Raymond, who had denied the reality of climate change and called environmental advocates "extremists." Right off the bat, Tillerson acknowledged that climate change is a serious issue. Second, as I mentioned above, just a month after UCS released its report, ExxonMobil's VP for public affairs stated unambiguously that the company had pulled the plug on its contrarian network.

Journalists apparently took that misleading statement at face value, and so did advocates. By the end of the 2007, the Exxpose Exxon campaign--which noticed a 33 percent drop in the company's contrarian funding between 2005 and 2006--declared victory and closed up shop. Meanwhile, the kinder, gentler Tillerson hewed to the same path as his predecessor and, with much less fanfare, the company continued to ply contrarian think tanks with grants, as did a small number of other fossil fuel and auto industry benefactors.

How well has the press explained the link between these special interests and these think tanks over the last few years? Not very.

I recently sifted through the coverage of climate and energy issues from January 2011 through December 2012 by eight top news organizations to see how they identified key think tanks and advocacy groups funded by the fossil fuel industry. My sample included stories, editorials, opinion pieces and interviews from the Associated Press, NPR, the political trade journal Politico, and six leading newspapers: the Los Angeles Times, New York Times, USA Today, Washington Post and Wall Street Journal.

I focused at how these media outlets described eight leading fossil fuel industry-backed policy groups I call the "Oil Eight": the American Enterprise Institute, Americans for Prosperity, Cato Institute, Competitive Enterprise Institute, Heartland Institute, Heritage Foundation, Institute for Energy Research (and its political arm, American Energy Alliance), and Manhattan Institute for Policy Research.

Overall, the news organizations mentioned the Oil Eight's funding in only a third of the nearly 360 relevant pieces I found. If that sounds bad, it was considerably worse when it comes to how they covered the three Oil Eight think tanks that were still receiving grants from ExxonMobil between 2006 and 2011--the Manhattan Institute, Heritage Foundation and American Enterprise Institute. The news outlets referenced their funding in only two of 89 pieces that mentioned the think tanks, and one was a column by the New York Times' public editor--what other papers call an ombudsman--responding to complaints that the Times does not disclose its outside op-ed writers' financial conflicts of interest. (For more information about my findings, click here.)

Let's take a look at some of the coverage.

Manhattan Institute Fellow Attacks Renewables

The Manhattan Institute for Policy Research is a multi-issue, pro-market, anti-government think tank based in New York City. Between 2001 and 2011, ExxonMobil and Charles Koch's Claude R. Lambe Charitable Foundation gave the institute $460,000 and $1.9 million respectively.

Ten of the Manhattan Institute's 24 citations over the two years I surveyed were opinion pieces in the Wall Street Journal by Robert Bryce, an institute fellow. Before joining the Manhattan Institute, Bryce, a former newspaper reporter, worked for the Institute for Energy Research, which over the years has been funded by the American Petroleum Institute, ExxonMobil and the Claude R. Lambe Charitable Foundation.

Most of Bryce's Wall Street Journal columns sang the praises of oil and coal and denigrated the potential of wind and other renewable energy technologies. For example, his May 4, 2012, column, "Gouged by the Wind," claimed that state standards requiring utilities to ramp up their use of renewables would significantly raise electricity rates--despite evidence to the contrary. Bryce rested his argument on his own, thoroughly debunked February 2012 Manhattan Institute study and an equally flawed Koch-funded study by the Beacon Hill Institute at Suffolk University.

None of the author bios at the end of Bryce's Journal columns disclosed the institute's fossil fuel industry ties. To be fair, however, the Journal is not alone. None of the newspapers in my survey provided that kind of information.

The New York Times, for example, published a Bryce op-ed in June 2011 titled "The Gas is Greener." In the piece, Bryce overstated how much land large-scale renewable energy projects would need to buttress his argument that natural gas and nuclear power make more sense, ignoring the fact that they come with their own set of land-use issues. The author's bio at the end of the column identified him as a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute and the author of Power Hungry: The Myths of "Green" Energy and the Real Fuels of the Future. Here again, readers deserved to know that two key Manhattan Institute funders--ExxonMobil and Charles Koch--are in the natural gas business.

Heritage Fellow Disputes Carbon Dioxide-Global Warming Link

The eight news organizations did a similarly poor job identifying the Heritage Foundation, the multi-issue, anti-regulation behemoth founded in 1973 to counter the raft of environmental, consumer and workplace protections signed into law during the Nixon administration. The news outlets mentioned funding sources in only one of 39 stories citing Heritage during the two years I checked. During the last decade, Heritage has received $535,000 from ExxonMobil (2001-11), $100,000 from General Motors (2003-07), and $3.69 million from Charles Koch's Claude R. Lambe Charitable Foundation (2001-10).

Heritage is not known for its climate work, but that didn't matter. Reporters still called Heritage fellows for the "other side" of the story.

Heritage was cited in seven articles and one op-ed in the Washington Post, for example. The lone op-ed--by Mike Tidwell of the Chesapeake Climate Action Network--did refer to the climate "disinformers" at the think tank, but Tidwell doesn't work for the paper. Meanwhile, two of the articles merely labeled the Heritage Foundation "conservative" and the other five didn't bother to describe it at all. None of the stories informed readers that ExxonMobil and Charles Koch support Heritage. Equally egregious, Post reporters provided Heritage spokespeople space to make false assertions and failed to refute them.

Three of the articles quoted Diane Katz, a Heritage research fellow. In one of the stories, which ran in March 2011, Katz told Post reporter Darryl Fears: "There's no strong consensus on whether carbon dioxide causes global warming or climate change." In fact, there is an overwhelming consensus among scientific institutions worldwide.

Later that year, longtime Post environment reporter Juliet Eilperin asked Katz for her reaction to the Obama administration placing limits on carbon emissions from new power plants and strengthening vehicle fuel efficiency standards. "Environmental regulation should be about protecting public health," Katz said, "and not about creating green jobs and mitigating hypothetical risk." In fact, there is nothing hypothetical about global warming, and it poses a serious threat to public health.

Who is Diane Katz? Like a number of her Heritage colleagues, Katz spent some time at smaller Koch-funded organizations before joining the think tank in 2010. After a stint at the Detroit News as a reporter and editorial writer, she worked for the Koch- and ExxonMobil-funded Fraser Institute, a libertarian think tank in British Columbia; and the Koch-funded Mackinac Center for Public Policy, a Michigan-based libertarian think tank.

USA Today also sporadically labeled Heritage "conservative" and, like the Post, the paper didn't mention where Heritage gets its funding. David Kreutzer was USA Today's favorite Heritage talking head. The paper quoted him in 11 of the 13 stories that cited the think tank over the two-year period I reviewed.

USA Today energy and environment reporter Wendy Koch (pronounced "Kotch" and no relation to the Koch brothers) cited Kreutzer in an August 16, 2011, story on how cities are preparing for global warming-induced sea level rise, calling him a "climate change skeptic." Koch wrote that Kreutzer told her "there have always been 'variations in weather' so it makes sense to prepare for storms," but he warned "cities may waste money if their regulations are based on 'hysterical' projections of sea level rise."

Two months later, on October 4, Koch wrote a story about federal subsidies to the solar industry and again called Kreutzer, who, in her words, told her "the government has no business subsidizing the industry." Never mind that the federal government has been giving the oil and gas industry significantly more in subsidies and tax breaks for a much longer time--an average of $4.86 billion annually in today's dollars for the last 95 years, in fact.

Who is David Kreutzer? Before joining Heritage in 2008, he worked for Richard Berman, whose PR firm, Berman and Company, runs two-dozen industry front groups whose raison d'être is to block or weaken consumer, environmental and workplace safeguards. Like Katz, Kreutzer also has a previous Koch network connection. He got his doctorate in economics from George Mason University's economics department, which currently shares roughly half its faculty with the Koch-founded and Koch-funded Mercatus Center, an anti-regulation, climate contrarian think tank housed on the GMU campus. Over the last decade, the center received $25,000 from the American Petroleum Institute (2008), $240,000 from ExxonMobil (2003-09), and $5.7 million from the Charles G. Koch Charitable Foundation (2002-08).

AEI Scholar Calls for Ending Federal Subsidies for Solar, But Not for Oil

The American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research (its official name) has played a relatively bit part in the climate and energy debate. Even so, the think tank, which was founded in 1938, was cited in 26 climate and energy stories and op-eds over the two years I reviewed. None of the pieces mentioned that AEI is partly supported by the fossil fuel industry, let alone that it was the beneficiary of $60,000 from the American Petroleum Institute, $3.04 million from ExxonMobil, and $1.1 million from the three main Koch family foundations between 2001 and 2011.

AEI's principal climate and energy spokesmen during the period I reviewed were Steven Hayward and Kenneth Green. Like Diane Katz and David Kreutzer at Heritage, Hayward's and Green's résumés illustrate how fossil fuel industry network experts move from one contrarian echo chamber institution to another.

Hayward--who called for expanding domestic oil production in an April 2011 Wall Street Journal op-ed and predicted California's carbon emission cap-and-trade program "will wither and die an ignominious death" in an October 2011 New York Times story--has a doctorate in American studies. Before joining AEI, he was a contributing editor at the ExxonMobil-, Koch-funded Reason Foundation's monthly magazine and a fellow at the ExxonMobil-, Koch-funded Heritage Foundation. He is a now a visiting scholar at the University of Colorado in Boulder and has been a senior fellow with the ExxonMobil-, Koch-funded Pacific Research Institute for Public Policy for a number of years.

Green--who denounced federal subsidies for solar power--but not for oil--in a March 2011 Wall Street Journal story--has a doctorate in environmental science and engineering, but has never published any peer-reviewed articles on climate. Over the years, he has made the rounds on the fossil fuel industry-funded circuit. Before joining AEI, he was the director of the ExxonMobil-, Koch-funded Environment Literacy Council, an education project of the ExxonMobil-, Koch-funded George C. Marshall Institute that stressed the uncertainties of climate science and published a report in 2007 that questioned whether global warming is occurring. Prior to his two-year stint at the Environment Literacy Council, Green was chief scientist at the ExxonMobil-, Koch-funded Fraser Institute and the ExxonMobil-, Koch-funded Reason Foundation. He also has served as a Heartland Institute expert. He is now back at the Fraser Institute, serving as a senior director.

Do Robert Bryce, Diane Katz, David Kreutzer, Steven Hayward and Kenneth Green have a right to express their opinions on climate and energy issues? Certainly. But at the same time the public has a right to know how shallow their scientific expertise might be, if what they are saying is indeed correct, and what interested parties are underwriting their think tanks.

Collectively, the elite eight news organizations I reviewed cited funding sources for the Manhattan Institute, Heritage Foundation and American Enterprise Institute in only 2 percent of the relevant pieces they ran during the two years I surveyed. The public deserves more, especially when we're talking about such a critically important issue as climate change. #

Elliott Negin, the director of news and commentary at the Union of Concerned Scientists, is a former NPR news editor and managing editor of American Journalism Review.

Charles Koch (above) and his brother David (below) gave nearly $50 million to a network of climate contrarian think tanks and advocacy groups from 2002 through 2011.

Part 4: The Koch Brothers Overtake ExxonMobil as Top Contrarian Patron

For several decades, Charles G. and David H. Koch -- owners of the Wichita-based oil, gas and coal conglomerate, Koch Industries -- surreptitiously financed political and policy organizations favoring "free enterprise" and opposing government regulation. At the same time, the billionaire brothers developed an unsavory reputation with at least one philanthropy watchdog.

In 2004, the National Committee on Responsive Philanthropy (NCRP) published a comprehensive study on the funding strategies of 79 conservative foundations to support 350 public policy think tanks at the national, state and local level. Three of those foundations were ones controlled by the Kochs -- the Charles G. Koch Charitable Foundation, the David H. Koch Charitable Foundation and the Claude R. Lambe Charitable Foundation.

The NCRP's take on the Kochs' funding agenda? It concluded that their family foundations support think tanks that "do research and advocacy on issues that impact the profit margin of Koch Industries." "In touting limited government and free markets," the NCRP found, "these organizations doubt the dangers of various chemicals, environmental pollutants and global warming, as well as challenge research efforts documenting these hazards."

"... It makes sense that the Kochs would fund such anti-environment organizations," the study authors added, "given their seedy past of environmental violations and lawsuits."

To be sure, Koch Industries has a long environmental crime rap sheet. Over the years, the company has had to pay tens of millions of dollars in fines and hundreds of millions in cleanup costs. At the same time, the brothers' grantees have been particularly critical of environmental safeguards on the books as well as proposed ones, such as a carbon emissions cap-and-trade system, which would certainly have a significant impact on Koch Industries' bottom line.

As it turns out, a number of the think tanks the Kochs began supporting more than 25 years ago -- the Cato Institute, Competitive Enterprise Institute, Heartland Institute and Heritage Foundation, among them -- are the very same policy shops that represented the tobacco and pharmaceutical industries in their fight against the Food and Drug Administration in the mid-1990s. And, as I pointed out earlier in this series, ExxonMobil, General Motors and other fossil fuel interests enlisted these same think tanks at the turn of the century to sow doubt about the reality of global warming and blunt any attempts in Congress to pass climate change legislation.

In the early 2000s, there was a bipartisan bill kicking around Congress that would cap and reduce carbon emissions from power plants, refineries and other industries. The legislation -- first introduced in the Senate in 2003 by John McCain (R-Ariz.) and Joe Lieberman (D-Conn.) and in the House in 2004 by Wayne Gilchrest (R-Md.) and John Olver (D-Mass.) -- was reintroduced in both houses in 2005. In contrast with the Bush administration's unsuccessful voluntary approach, the proposed bill called for establishing a mandatory, market-based cap-and-trade system to cut emissions.

The McCain-Lieberman bill apparently spooked the Kochs, who operate oil refineries in Alaska, Minnesota and Texas and supply coal to Midwestern utilities. In 2005, their three main family foundations doubled their contrarian group contributions from the previous year to $4.2 million, surpassing ExxonMobil, which spent $3.48 million. A year later, the Kochs' donations doubled again, reaching a peak of $8.59 million, more than three times what ExxonMobil gave that year. All told, the three main Koch family funds would funnel more than $43 million to the contrarian network from 2005 through 2011, while ExxonMobil would hand out $12 million -- less than a third -- to many of the same groups.

The Kochs Fly Under the Media Radar

By 2005, the Kochs had quietly replaced ExxonMobil as the uber patron of climate contrarianism, but nobody knew it. The news media were only just beginning to pay attention to ExxonMobil's funding activities and, outside of the fossil fuel industry -- and Koch grantees, of course -- who had ever heard of Koch Industries? As David Koch liked to joke, his family-owned conglomerate, whose annual revenues are now estimated at $100 billion, was "the largest company you've never heard of."

At least one national news organization, however, was on to the Kochs -- for about a news-cycle nanosecond. Thirteen years ago, on January 29, 2000, the Washington Post ran a front-page story by Dan Morgan, "Think Tanks: Corporations' Quiet Weapon; Nonprofits' Studies, Lobbying Advance Big Business Causes," which profiled a conservative, multi-issue, small government policy group called Citizens for a Sound Economy (CSE).

"CSE was founded by two free-spirited Midwestern oil and gas tycoons, the brothers David H. and Charles G. Koch, principal owners of Koch Industries of Wichita," Morgan reported. "Foundations they controlled helped found Cato, CSE and other less-known think tanks committed to the Koch's libertarian beliefs."

Morgan's investigation turned up documents that, as he explained, "provide a rare look at think tanks' often hidden role as a weapon in the modern corporate political arsenal. The groups provide analyses, TV advertising, polling and academic studies that add an air of authority to corporate arguments -- in many cases while maintaining the corporate donor's anonymity."

Sound familiar?

After Morgan's story, however, it was radio silence, at least at the national level. There was no follow up by the Post, and no attention paid by any other news organizations besides local papers in Houston, Seattle, St. Louis and Wichita, which ran one-off stories over the next five years that linked the Kochs to conservative think tanks. The "Kochs as under-writers" story essentially died, despite the fact that, between 2002 and 2007, they spent nearly $24 million on climate contrarian policy groups -- and millions more on think tanks and lobbyists working on their other pet issues.

It wasn't until 2008 when the news media -- at least at the local level -- began to take notice again. What piqued reporters' interest, appropriately enough, was Americans for Prosperity (AFP), one of the two multi-issue, tea party-affiliated groups that Citizens for a Sound Economy spawned in 2004 when it broke up, the other being FreedomWorks. David Koch, who is credited as AFP's founder, is the chairman of the group's foundation.

In 2008, AFP kicked off a cross-country "Hot Air Tour" featuring hot air balloon rides and the slogan "Global Warming Alarmism: Lost Jobs, Higher Taxes, Less Freedom." The national print press ignored the story. Besides Fox and MSNBC, national television and cable news shows didn't pay much attention, either, and only MSNBC's Rachel Maddow Show mentioned the Koch-AFP link. Local newspapers where the tour touched down, on the other hand, covered it like the circus coming to town. But only five out of 38 briefs and articles those papers ran on the tour in 2008 and 2009 reported that the Kochs backed AFP.

So where was the Washington Post?

Remarkably, it took the paper nearly a decade to rediscover the Koch-think tank connection that Dan Morgan reported back in 2000. Although the paper ran 24 stories on AFP from 2004 through 2009, only one -- which ran in August 2009 -- linked the group to the Kochs. It also was the only story that mentioned that AFP disputed climate science. Most of the other stories merely identified it as a "conservative" or "small government" group.

A Public Interest Group Blows the Whistle (Again)

The Kochs' years of relative anonymity came to an end in early 2010 and, as in the case of ExxonMobil, it was largely due to the work of a public interest group.

As I reported earlier in this series, ExxonMobil was thrust into the public eye in the summer of 2005 by the Exxpose Exxon campaign, which was sponsored by a dozen public interest groups, and again in early 2007, when a Union of Concerned Scientists report disclosed the company's role in bankrolling climate contrarians. The Koch brothers, meanwhile, were outed by a March 2010 Greenpeace report revealing that between 2005 and 2008, the Kochs spent significantly more than ExxonMobil on virtually the same network of contrarian groups to attack climate science and undermine government attempts to address global warming.

Before Greenpeace released "Koch Industries Secretly Funding the Climate Denial Machine," the group's research director, Kert Davies, met with journalists at a number of news organizations, including ABC, Newsweek and the New York Times, to go over the report's findings. "The number of serious journalists who didn't even know the name David Koch or Koch Industries was stunning," Davies, a lead author of the report, told Politico, a political trade journal. "It was because they were intentionally invisible. They really liked it the way it was. So one of our main objectives was to make them a household name...."

David Koch is bullish on global warming. "The Earth will be able to support enormously more people," he says, "because a far greater land area will be available to produce food."

The Greenpeace report definitely created a media buzz. In July, New York magazine profiled David Koch, who told the magazine that global warming is a good thing because it will lengthen growing seasons in the northern hemisphere. Around the same time, economist Paul Krugman disclosed the Koch-climate contrarian link in the New York Times for the first time. A month later, the Washington Post profiled AFP, delving into the details of its Koch connection. And the New Yorker ran a 10,000-word opus on the brothers' family history, libertarian philosophy, and influence on conservative politics that prominently cited Greenpeace's findings.

All of the sudden, the Kochs were fair game.

News Media Tie AFP to the Kochs, But Fail to Connect Other Grantees

Despite the fact that more journalists are now aware of the Koch brothers, many still miss the fact that AFP is not the only policy group that lives off Koch largesse. For instance, AFP is just one of approximately 40 think tanks and advocacy groups the Kochs underwrite to promote their climate and energy agenda. Regardless, journalists still more often than not fail to mention they're Koch surrogates.

If you've read any of the previous installments in this series, you know that I recently reviewed climate and energy coverage from 2011 and 2012 to see how often top news organizations disclosed funding sources for AFP and seven other climate contrarian groups I call the "Oil Eight." My survey included stories, editorials, opinion columns and interviews from the Associated Press, NPR, Politico, and six leading newspapers: the Los Angeles Times, New York Times, USA Today, Washington Post and Wall Street Journal.

Given there's a brighter spotlight on the Kochs and a heightened awareness of post-Citizens United money flooding the political system, it's not surprising that these news outlets mentioned AFP more than any other of the Oil Eight. Overall, nearly 30 percent of the 357 climate and energy stories in my sample cited AFP at least in passing, and a number focused squarely on the group and its activities. Many of the stories referenced the group's multimillion-dollar TV political ad campaign last year. A number of the news organizations in my survey--the Los Angeles Times, New York Times, Politico and Washington Post, in particular--devoted considerable space to that story.

Likewise, the news organizations did a better job identifying AFP as fossil fuel industry-funded group. Seventy of 102 pieces citing AFP -- 69 percent -- linked the group to the Kochs, whose family foundations gave AFP more than $5.75 million between 2005 and 2010. (For more on my survey results, click here.)

Discounting their AFP coverage, the news outlets cited fossil fuel industry funding sources in only 24 percent of 255 pieces that mentioned the other seven climate contrarian groups. Those seven groups -- the American Enterprise Institute, Cato Institute, Competitive Enterprise Institute, Heartland Institute, Heritage Foundation, Institute for Energy Research (and its political arm, American Energy Alliance), and Manhattan Institute for Policy Research -- together received $10 million from the three main Koch family foundations between 2001 and 2011. (For more details, see this list of the Oil Eight's fossil fuel industry funding.)

American Energy Alliance vs. Obama Campaign: Dueling Ads

Another Oil Eight member -- the American Energy Alliance (AEA) -- also got caught in the glare of political campaign coverage last year. Although the eight news outlets in my survey were not as attentive to its funding as they were with AFP, they still managed to tie the alliance to the fossil fuel industry in 43 percent of the 61 stories that cited the group in 2011 and 2012.

Most of the stories citing the alliance -- the political arm of a small, single-issue group called the Institute for Energy Research -- focused on its TV ad battle with the Obama reelection campaign. A number of those stories that mentioned the alliance's funding relied on the Obama camp's charge that the AEA is a "front group for big oil" without going the extra mile to nail down that fact. For example, an April 3, 2012, story by Associated Press political reporter Andrew Miga stated: "There's no way of knowing if Obama's claim that the American Energy Alliance ad is funded by Big Oil is true; the alliance does not disclose its donors or contribution amounts."

If Miga had checked either the Conservative Transparency or Foundation Center website, he would have been able to confirm that during the last decade, the alliance's parent organization received $160,000 from the American Petroleum Institute (2008-10), $337,000 from ExxonMobil (2002-07), and $227,500 from Charles Koch's Claude R. Lambe Charitable Foundation (2001-07).

To his credit, Miga did report that AEA's president, Thomas Pyle, is a former Koch Industries lobbyist and that AEA's arguments "are the same ones made by oil companies and their allies." All told, the Associated Press cited AEA's fossil fuel industry connection in three of the six stories it ran over the two-year period I checked.

Politico, meanwhile, mentioned the alliance's funding in 11 of the 23 stories it ran citing the group. The Washington Post, on the other hand, reported it in only one of five stories. That story, "Energy issue gets jolt of ads," by T.W. Farnum, called the alliance "an advocacy group that pushes for less government regulation of the [energy] industry," and reported that it "spent $3.6 million on an ad attacking Obama over gas prices, Solyndra, the Keystone pipeline and his opposition to drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge."

Farnum then paraphrased an alliance spokesman, who told him the group "received most of its funding in its last tax year from individual families, including many with newfound wealth from domestic drilling." That does make it clear that the alliance represents the oil and gas industry, but most readers would presume that the AEA is a mom and pop operation. Little would they know that the American Petroleum Institute, ExxonMobil and the Koch brothers have been funding the group for years. #

Note: In part 3 of this series I mentioned that Heritage Foundation fellow David Kreutzer previously worked for Richard Berman, who runs a network of corporate front groups. On May 19, the Boston Globe published a front page exposé of Berman, focusing on his Center for Consumer Freedom, which represents the interests of the restaurant and food industries.

Elliott Negin, the director of news and commentary at the Union of Concerned Scientists, is a former NPR news editor and m

Part 5: Science-Free Zones at the Heartland and Cato Institutes

The Heartland Institute has a long history of peddling half-baked nonsense. Over the years, the group has dismissed the health threat posed by second-hand smoke, ridiculed the evidence for acid rain as "flimflam," and criticized the "hasty phase-out" of chlorofluoro-carbons, which were destroying the atmosphere's ozone layer. More recently, the Economist called Heartland "the world's most prominent think tank promoting skepticism about man-made climate change," and the magazine didn't mean it as a compliment.

Given Heartland's penchant for misrepresenting science, you would think reporters would be curious about who finances its work. You would be wrong.

I recently reviewed climate and energy coverage from 2011 and 2012 to see how often top news organizations disclosed funding sources for Heartland and seven other climate contrarian groups I call the "Oil Eight." My survey included stories, editorials, opinion columns and interviews published or aired by the Associated Press, NPR, the trade journal Politico, and six leading newspapers: the Los Angeles Times, New York Times, USA Today, Washington Post and Wall Street Journal. (For my survey results, click here.)

There were two breaking news stories that provided an opportunity for reporters to disclose Heartland's benefactors during that two-year period, but the news outlets cited funding in only 11 of 54 pieces they ran that mentioned the think tank. That's only 20 percent of the time.

Before the spring of 2012, the Chicago-based group was probably best known as the host of the largest annual international climate contrarian conference. By the end of last year, it was best known for posting a billboard in the Chicago metro area likening climate scientists to Unabomber Ted Kaczynski. The billboard, which Heartland had planned to be the first in a series featuring Osama bin Laden, Charles Manson and Fidel Castro, displayed a mug shot of Kaczynski and the headline: "I still believe in Global Warming. Do you?" The billboard triggered an immediate public backlash, forcing Heartland to take down it just a day after it went up. It also sent a number of Heartland's funders scurrying for the exits.

The billboard fiasco, which happened in early May, came on the heels of another story that put Heartland under the media microscope. Peter Gleick, a climate scientist and president of the Pacific Institute for Studies in Development, Environment and Security, misrep-resented himself to pry fundraising and strategy documents out of an unsuspecting Heartland employee and leaked them to reporters. This time public opprobrium was directed at Gleick for his subterfuge, but given the documents revealed some of Heartland's funding sources, as well as its plans to develop misleading climate curriculum materials for public schools, the story provided an opening for reporters to take a closer look at the group.

The New York Times, which cited Heartland more than any of the other news organizations in my survey, ran 13 stories and blogs on the purloined documents between mid-February and early June. Only two, a February 15 blog by Andrew C. Revkin and a February 16 article by Justin Gillis and Leslie Kaufman, mentioned Heartland's funding. Revkin offered little information, however, writing that Heartland was "backed by industry and independent donors opposed to government regulation."

Gillis and Kaufman provided more detail. "Perhaps the most intriguing aspect of the Heartland documents was what they did not contain: evidence of contributions from the major publicly traded oil companies, long suspected by environmentalists of secretly financing efforts to undermine climate science," they wrote. "But oil interests were nonetheless represented. The documents say that the Charles G. Koch Charitable Foundation contributed $25,000 last year and was expected to contribute $200,000 this year. Mr. Koch is one of two brothers who have been prominent supporters of libertarian causes as well as other charitable endeavors. They control Koch Industries, one of the country's largest private companies and a major oil refiner."

In fact, during the last decade, major publicly traded oil companies have been funding Heartland. If Gillis and Kaufman had dug a little deeper, they would have discovered that ExxonMobil gave Heartland more than $530,000 (2001-2011) while the American Petroleum Institute--the oil and gas industry's trade association--slipped the think tank $25,000 (2008). Two of the Big Three Detroit automakers also chipped in. Chrysler donated $105,000 (2004-2006); General Motors, $165,000 (2004-2010). All had a vested interest in quashing government action on climate change.

The subsequent 10 stories and blogs the Times ran mentioning the Gleick affair called Heartland "libertarian" or "anti-regulatory," but didn't say anything about its funding. Likewise, the five blogs and stories the Times ran on Heartland's Unabomber billboard labeled the group "conservative," "libertarian" or "right wing" and also avoided the funding topic. All told, only five of 22 Times stories citing Heartland over the two-year period I reviewed mentioned the think tank's benefactors.

The Los Angeles Times--the fourth largest paper in the country--ran five articles, one column and one editorial citing Heartland from January 2011 through December 2012. None of the articles mentioned the think tank's funding sources. Reporter Neela Banerjee, who wrote three of them, merely identified it as "conservative."

A February 29, 2012, column on the Gleick controversy by the paper's Pulitzer Prize-winning business columnist, Michael Hiltzik, was the only one of the seven pieces that touched on the funding issue. He called Heartland "a nest of global warming deniers and corporate anti-regulators" and explained that "[o]ver the years its backers have included ExxonMobil and the foundations of the Koch family and Richard Mellon Scaife."

The editorial, which ran on February 20, 2012, didn't cite funding sources, but it ripped the heart out of Heartland. Check out this excerpt:

Leaked documents from the Heartland Institute in Chicago, one of many nonprofits that spread disinformation about climate science in hopes of stalling government action to combat global warming, reveal that it is working on a curriculum for public schools that casts doubt on the work of climatologists worldwide. Heartland officials say one document was a fake, but the curriculum was reportedly discussed in others. According to the New York Times, the curriculum would claim, among other things, that "whether humans are changing the climate is a major scientific controversy."

That is a lie so big that, to quote from Mein Kampf, it would be hard for most people to believe that anyone "could have the impudence to distort the truth so infamously." On one side of the "controversy" are credentialed climatologists who publish in reputable, peer-reviewed scientific journals and agree that the planet is warming and that humans are to blame; on the other are fossil-fuel-industry-funded "experts" who tend to have little background in climatology and who publish non-peer-reviewed papers in junk magazines disputing established truths. These are quickly debunked, but not before their findings have been reported by conservative blogs and news outlets, which somehow never get around to mentioning it when these studies are proved to be badly flawed.

Despite the fact that the Los Angeles Times only mentioned Heartland's funders in one of seven pieces, it did the best overall job of any of the general interest news organizations in my survey, mentioning the Oil Eight's benefactors 44 percent of the time. Only Politico, a narrowly focused political trade publication, did as well.

The Times track record outing climate contrarian funders may be in jeopardy, however. Koch Industries is reportedly considering buying the newspaper and its parent Tribune Company's seven other regional papers, which include the Chicago Tribune, Baltimore Sun, Orlando Sentinel and Hartford Courant. If that happens, Hiltzik and Los Angeles Times Editorial Page Editor Nicholas Goldberg both better look for a new job.

The Scientifically Catatonic Cato Institute

Another Oil Eight member, the Cato Institute, also has long disparaged environmental and public health safeguards. Over the years, its "scholars" have argued that the science behind the worldwide ban on chlorofluorocarbons was "distorted, even subverted"; that concerns about lead, asbestos, radon and other dangerous substances amounted to "hysteria"; and that government efforts to curb carbon emissions would be too expensive, ineffective and unnecessary.

The Cato spokesman who scoffed at the chlorofluorocarbon threat was Patrick Michaels, who now runs the organization's Center for the Study of Science. Although Michaels has a doctorate in agricultural climatology and spent much of the 1980s studying crop climate sensitivity, by the 1990s he was editing a coal industry-funded quarterly newsletter, World Climate Review, which attacked mainstream climate science; and by August 2010, Michaels estimated that 40 percent of his funding came from the oil industry.

Given Michaels is one of only a handful of bona fide climate scientists who buck the prevailing view that manmade global warming poses a serious threat, he moonlights as an adviser to other ExxonMobil- and Koch-funded think tanks. Those groups include at least three other Oil Eight members, the Competitive Enterprise Institute, Heritage Foundation and Heartland Institute, which commissioned Michaels to speak at four of its annual climate-science bashing conferences.

Instead of publishing studies in peer-reviewed science journals, Michaels writes opinion columns for the Washington Times and Forbes. It was in the Times where Michaels made his specious arguments against banning chlorofluorocarbons, and that's where he claimed earlier this year that the world's average temperatures have been "flat" for nearly two decades.

"My greener friends are increasingly troubled by the lack of a rise in recent global surface temperatures," he wrote on January 17. "Using monthly data measured as the departure from long-term averages, there's been no significant warming trend since the fall of 1996. In other words, we are now in our 17th year of flat temperatures."

In fact, 2012 was the ninth warmest year since data were first collected in 1880, according to NASA. With the exception of 1998, the nine warmest years have occurred since 2000, and the hottest years on record were 2005 and 2010.

The Washington Times op-ed wasn't the first time Michaels has made this baseless assertion. He told USA Today's weather and climate reporter Doyle Rice essentially the same thing for a January 13, 2011, story reporting that 2010 tied with 2005 as the world's warmest year since 1880. Rice first quoted David Easterling, chief of scientific services at the National Climatic Data Center, who said, "This warmth reinforces the notion that we're seeing climate change." Rice then quoted Michaels:

Pat Michaels, a climatologist with the Cato Institute in Washington, disagrees. "If you draw a trend line from the data, it's pretty flat from the 1990s," he says. "We don't see much of a warming trend over the past 12 years."

He says gloom-and-doom projections are likely to be too hot. "The projections will have to come down," Michaels says.

Doyle did go on to contradict Michaels, explaining that "[n]ine of the Earth's 10 warmest years on record have occurred since 2001, and all 12 of the warmest years have occurred since 1997." But that likely confused readers. Why would Doyle quote Michaels and then point out that he's wrong, and why would Michaels say something so disingenuous in the first place?

Doyle could have explained that Cato received $110,000 from ExxonMobil (2001-06), $95,000 from General Motors (2003-09), and $2.79 million from the three main Koch family funds (2001-10) over the last decade. Mentioning that Koch Industries owners Charles and David Koch founded the think tank in the mid-1970s and sit on its board also may have helped clear up any confusion about Michaels' agenda: The fossil fuel industry pays him to sow doubt about climate science.

USA Today published three other climate and energy stories citing Cato during the two-year period I reviewed. Those articles merely described the think tank as "libertarian" and, like Doyle's story, failed to cite its funders. But USA Today was not alone. Altogether, the eight news organizations I tracked disclosed Cato's funding in only two of the 21 climate and energy stories they ran mentioning the think tank in 2011 and 2012. That means they failed 90 percent of the time to explain whose interests Cato serves--and it's definitely not the public's. #

Elliott Negin, the director of news and commentary at the Union of Concerned Scientists, is a former NPR news editor and managing editor of American Journalism Review.

David Koch (above) has acknowledged that he and his brother Charles exert tight control over their grantees' agendas. "If we're going to give a lot of money," he said, "we'll make darn sure they spend it in a way that goes along with our intent." (Getty Images)

Part 6: It's Time for the Media to Stop Giving Climate Contrarians a Free Ride

In October 2011, a government and industry watchdog group called the Checks and Balances Project sent a letter to the New York Times public editor -- what other papers call an ombudsman -- criticizing the paper for failing to report op-ed contributors' funding sources. Signed by more than 50 journalists and educators, the letter called on the paper to "set the nation's standard by disclosing financial conflicts of interest that their op-ed contributors may have at the time the piece is published."

The letter singled out an op-ed by Manhattan Institute fellow Robert Bryce as a prime example. To try to make the case that natural gas and nuclear power are more advantageous than solar, wind and other renewable technologies, Bryce overstated how much land renewable energy projects would need and ignored his favored energy sources' short-comings. Checks and Balances pointed out that Bryce's author bio failed to mention that two Manhattan Institute funders -- ExxonMobil and the Koch brothers -- are in the natural gas business.

The paper's public editor at the time, Arthur S. Brisbane, responded in an October 29 column, "The Times Gives Them Space, but Who Pays Them?" "...[E]xperts generally have a point of view," Brisbane wrote. "And the Manhattan Institute's dependence on this category of funding [the fossil fuel industry] is slight -- about 2.5 percent of its budget over the past 10 years. But the issue of authorial transparency is an important one, albeit one that isn't always simple."

Brisbane then asked the Times editorial page editor, Andrew Rosenthal, to weigh in--and then gently disagreed with him.

As for Mr. Bryce, Mr. Rosenthal said the Op-Ed article itself made very clear that he was a proponent of traditional energy sources. The Manhattan Institute is "well known for its pro-market stances, including its skepticism of subsidies for alternative energy," he said.

Certainly, the Manhattan Institute is well-known to some, including organized groups like the Checks and Balances Project, whose Web site's promotion of green energy makes clear that it is on the opposite side of the energy debate (something the petition does not mention).

But I don't think every reader knows what the Manhattan Institute is. So, while I recognize that the Times has limited space in print to provide more disclosure, I believe it should do more to help readers learn about outside Op-Ed contributors.

Did the Times take Brisbane's advice? Does it now disclose op-ed writers' financial conflicts of interest? Not that I've noticed. And I don't know of any newspaper that does.

That's a problem, not only when it comes to identifying contributing writers, but even more so when it comes to identifying sources cited in climate and energy news stories. More often than not, top U.S. news organizations fail to inform the public that spokespeople from seemingly independent climate contrarian policy groups are surrogates for the fossil fuel industry -- and that they are deliberately misrepresenting climate science and the potential of renewable energy.

To measure the extent of this oversight, I reviewed two years' worth of climate and energy stories from the Associated Press, the trade journal Politico, NPR, and six leading newspapers -- the Los Angeles Times, New York Times, USA Today, Washington Post and Wall Street Journal. It turned out that 68 percent of the time, these news organizations neglected to provide information about funding for eight prominent climate contrarian think tanks and advocacy groups I call the Oil Eight. (For my survey results, see the table below, and for more information, click here.)

The Oil Eight includes the American Enterprise Institute, Americans for Prosperity, Cato Institute, Competitive Enterprise Institute, Heartland Institute, Heritage Foundation, Institute for Energy Research (and its political arm, American Energy Alliance), and Robert Bryce's Manhattan Institute. Altogether they received $6.7 million from ExxonMobil and $15.76 million from the three main Koch family foundations between 2001 and 2011. (For more details, see this list of the Oil Eight's primary fossil fuel industry funding.)

Why Don't Journalists Disclose the Industry-Think Tank Connection?

Given that each of the news organizations I tracked mentioned funding sources on at least five occasions between January 2011 and December 2012, they can't claim to be unaware of the connection. So if they could mention fossil fuel industry funding once, twice, even five times, why didn't they mention it more often? I contacted a few reporters to find out.

One reporter echoed Brisbane's observation about limited space. "Just look at how few inches we get in print!" she responded in an email. "If we cite Heritage's funding source, we have to cite your [Union of Concerned Scientists'] funding source, and all of that takes space."

Space is definitely an issue. Reporters need space -- or time when it comes to radio and television -- to tell a complicated story like climate change. And space is harder to come by, at least in newspaper print editions, while broadcast reporters have only a few minutes to cram everything in. But given ExxonMobil and the Koch brothers are now the largest remaining climate contrarian funders, using the descriptor "fossil fuel industry-funded" at the very least to describe a contrarian group wouldn't take up much space or time. And it would signal loud and clear that the group is not impartial.

What about the reporter's contention that organizations like mine are fair game, too? In reality, there is a world of difference between the Oil Eight and the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS), as well as most other public interest groups. The Oil Eight are mercenaries. They represent the interests of their corporate funders, which have a clear financial stake in frustrating federal and state efforts to address climate change.

Unlike the Oil Eight, UCS -- which is supported by individuals and foundations -- will not accept corporate financial or in-kind contributions that would create an actual or even an apparent conflict of interest. Likewise, UCS will not accept funding from a company that could gain a competitive advantage or other benefit from our work. (For more information about UCS's funders, click here.)

Most public interest groups have very tight corporate funding restrictions or shun it altogether. So when a public interest group surreptitiously takes corporate money and promotes its financial interests -- which is what the Sierra Club did a few years ago--that revelation is big news because it's an anomaly. Reporters could write that same story about any one of the Oil Eight every day, but it would not be news. That's how they roll. And that's why it is critical for reporters to make their financial links explicit.

Another reporter picked up on one of Brisbane's other points. "We should make clear that the organization is not neutral; we should label it 'conservative' or 'libertarian,' for example," she said. "But if ExxonMobil or the oil industry is not the majority funder of the Competitive Enterprise Institute, it's too much detail for that level of passing reference."

Implicit in that view is the contention that if funders are not responsible for a significant portion of a multi-issue think tank's annual budget, they don't have much influence. In fact, they have a lot -- at least over the specific programs they underwrite. Just ask David Koch. He'll tell you that he and his brother Charles keep their grantees on a short leash. "If we're going to give a lot of money, we'll make darn sure they spend it in a way that goes along with our intent," Koch told Brian Doherty, an editor at Reason magazine. "And if they make a wrong turn and start doing things we don't agree with, we withdraw funding."

Meanwhile, the reporter's solution of labeling contrarian groups "conservative" or "libertarian" doesn't go far enough to explain whose interests they're serving -- and labels can be deceiving. For example, most if not all of the Oil Eight call themselves "free-market" policy groups. Last December, five of the Oil Eight -- the American Energy Alliance, Americans for Prosperity, Competitive Enterprise Institute, Heartland Institute and the Heritage Foundation's political arm, Heritage Action--held a press conference to urge Congress to kill a wind industry subsidy that was due to expire at the end of the year. In keeping with their free-market philosophy, they denounced the wind production tax credit as a "wasteful handout." At the same time, however, the five groups -- which, as I've pointed out repeatedly, receive fossil fuel industry funding -- maintain that eliminating subsidies for oil and gas companies would be "a massive tax hike on a vital sector of American industry." That hardly qualifies as a consistent free-market position.

Contrarians are Wrong on the Science & Wrong on the Policy

New York Times blogger Andrew C. Revkin, who left his full-time job as a Times environment reporter in 2009, addressed the issue of identifying think tank funders in a chapter he wrote for a 2007 book, Climate Change: What it Means for Us, Our Children, and Our Grandchildren. He published an excerpt in his Dot Earth blog in October 2010:

One practice that can improve coverage of climate and similar issues is what I call ''truth in labeling.'' Reporters should discern and describe the motivations of the people cited in a story. If a meteor-ologist is also a senior fellow at the [George C.] Marshall Institute, an industry-funded think tank that opposes many environmental regulations, then the journalist's responsibility is to know that connection and to mention it.