When Philanthropy Must Lead

In 1984, Aaron and Irene Diamond decided to give a significant portion of the money he had earned in real estate to the people and institutions of New York. Aaron Diamond died later that same year, but his wife went forward with their philanthropy as well as their plan to put a ten-year term limit on their foundation. Irene Diamond was driven particularly by a sense of urgency about the growing AIDS epidemic.

Because of complications due to the liquidation of Mr. Diamond's estate, the new foundation had two years to perform research before the ten-year countdown began. Then, between 1987 and 1996, the foundation awarded more than $200 million in grants. It focused on education and culture, but is best remembered for its funding of AIDS research.

In 1991, it helped create the Aaron Diamond AIDS Research Center, The Department of Health of the City of New York, the Public Health Research Institute and New York University School of Medicine all became partners in the project. The research center came under the direction of a microbiologist from UCLA, Dr. David Ho.

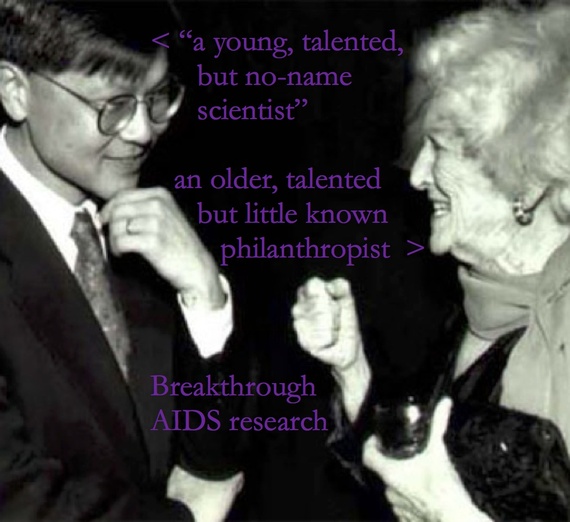

"I wanted somebody young who was really committed and had a drive to do good research," she told Alan R. Clyde in a 1998 edition of Foundation News and Commentary. "Most of my search committee of eminent doctors and scientists did not agree with me at the time. They wanted me to take somebody who was already well known...."

Instead, as reported in a case history published by Duke University's Center for Strategic Philanthropy and Civil Society, the top job went to Dr. Ho, whom Diamond called "a young, talented, but no name scientist." He would later call the job offer "a chance of a lifetime."

The center subsequently pioneered the use of combination drug therapy (protease inhibitors) to treat the disease -- helping to dramatically reduce the death rate from HIV. The foundation spent $50 million on AIDS research, making it the largest private supporter of such research in America at the time.

"Without the infusion of large sums of money," said Vincent McGee, former executive director of the foundation, "the research would have been delayed. We would have never seen the results that we did as soon as we did."

Defining an End Point to Your Giving

Some philanthropists follow the example of the Aaron Diamond Foundation and use an aggressive results-oriented approach to carry out their giving strategy. For them, giving is most effective -- and most likely to attract partners to leverage funds -- when there's a defined goal to be achieved by a certain date.

The strategic thinking behind this limited time horizon often includes the following points:

- Many social problems are most effectively fought by committing as much funding as possible while the issues are current and relevant.

- This early and intense funding can have a more decisive impact than smaller long-term grants from foundations that protect their endowments.

- Problems change over time, and a foundation endowed in perpetuity may not be flexible enough to work on new and unpredictable issues as they arise, due to outdated missions.

It's worth remembering, however, that the management demands on such an approach can be considerable. The deadline for ending giving, while seen by some as a great advantage, can become cumbersome if it is artificial. Addressing large social problems is rarely straightforward. And donors who want to achieve results in a limited amount of time may find they have underestimated the challenge.

Still, some philanthropic advisers tell their clients that the social investment they make through grants has far greater returns than the potential financial earnings of the foundation's endowment.

Paul Jansen is one of the founders of the nonprofit practice of McKinsey & Co. and remains a director emeritus of the organization. He says that for foundations to give only the five percent minimum per year represents "a tremendous cost to society." Foundations' endowments exist, he argues, to do social good. It's just a matter of when the benefit happens; in his opinion, the sooner the better.

FOR MORE: An online guide I wrote for Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors, funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation -- Setting a Time Horizon - How Long Should Your Foundation or Giving Program Last?

Cross-posted on Thinking Philanthropy