Let me introduce you to someone. In cold blood, this person killed a man -- who, even if he deserved to die, wasn't granted a trial -- and later rallied his followers to murder thousands of people who disagreed with his religious vision. When charged with a leadership role, this person whined, cowered in fear and tried every which way he could to shirk responsibility. His actions and arrogance also led his brother, sister and wife to distance themselves from him. Sound like someone you'd want to befriend, or even run into in a dark alley?

Meet Moses, the Egyptian, of biblical fame.

Many religious commentators throughout the ages have cited the humanity and fallibility of biblical characters as proof (in their estimation) of the truth of the Bible. Despite the Talmudic insistence that King David didn't sin ("whosoever says that David sinned, is nothing but mistaken"), neither by committing adultery with Bathsheba, nor by dispensing with her husband Uriah the Hittite -- the simple meaning of the text is that he was anything but angelic. Noah was a drinker; Judah did wrong by his daughter-in-law and bedfellow Tamar; Reuben didn't protect his younger brother Joseph; and Aaron helped build the Golden Calf.

If the women and men of the Bible ought to compel us -- as indeed they do for millions upon millions of people -- it is for the package of their merits and their sins. The two can't be disentangled, no matter how much some would love to try to do just that.

This has large implications for theologians, but it also means a good deal for religious art and culture, as well as art and culture that is critical of religion.

This has large implications for theologians, but it also means a good deal for religious art and culture, as well as art and culture that is critical of religion.

To say that Moses is a murderer can't be viewed as anti-Jewish, or even less persuasively, anti-Christian; it's simply a fact. Some might be offended by that characterization of Moses, and they may marshal arguments that the Egyptian taskmaster had it coming, or that Moses was justified in meting out capital punishment on those who bowed before the golden idol. But this is the stuff of biblical interpretation, rather than religion-bashing.

That's what makes the news about this new film, "Innocence of Muslims," which has been drawing fierce criticism from movie critics, commentators and even the Obama administration, so complicated.

Hillary Clinton, for example, has called it "an awful Internet video that we had nothing to do with," and added, "To us, to me personally, this video is disgusting and reprehensible." And according to some, the film has also been the true cause of violent riots overseas -- rather than a pretext for previously organized uprisings.

The manhunt for the person responsible for the film seems to be over, and there is news of some kind of connection to soft-core pornography. Those who find the alleged connection ironic should know the irony isn't new by any means; all they must do is look at the Bible (both testaments) to see the many leading roles assumed by prostitutes.

That the attacks that killed a U.S. ambassador and other innocent civilians and soldiers were evil, unprovoked and absolutely indefensible is obvious. That the situation required comment from the highest levels of the U.S. government is also clear. But that the statements should make artistic judgments about the film is bewildering.

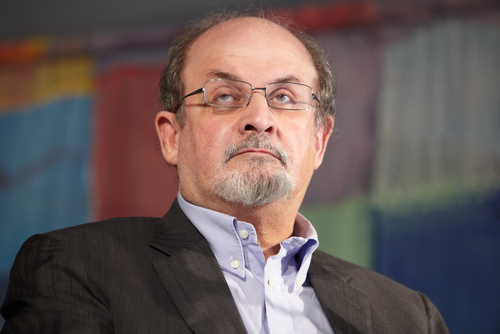

I've seen some of the clips of the film, and it's certainly nothing that's about to revolutionize the development of the medium. But to call it anti-Islam is about as useful as calling Monty Python's "Life of Brian" anti-Christian, or even Salman Rushdie's "The Satanic Verses" anti-Islam (see his recent, great piece in the New Yorker).

If a film or book advocates violent action against people of a certain faith, that work ought to be condemned. But the film's greatest provocations seem to be suggesting that the Muslim prophet may have had a bloody sword (which would have been typical of the day, and is supported by Islamic texts), and that he drew heavily on Old Testament texts (the same charge can be leveled, for example, at Jesus).

If the filmmakers' aim was to poke fun at, or even criticize, a religious or historical figure (or, to some, both), should it really be condemned by the State Department?

Perhaps that should be more appropriately left to those whose field is film. My friend Arnon Shorr, for example, offered this gem in a recent blog post: "I am proud to be a citizen of a country that embraces these freedoms, even if they result in trash."

Image: Salman Rushdie/Shutterstock. This post first appeared on the Houston Chronicle website.