WASHINGTON -- With Afghanistan's situation already looking more precarious than ever because of a re-energized Taliban insurgency and potential Islamic State growth, a congressional watchdog is now suggesting that one rare success story of the post-U.S. invasion era may have been oversold.

John Sopko, the special inspector general for Afghanistan reconstruction, revealed Thursday that he had recently written to the U.S. Agency for International Development to highlight his concerns about the $769 million USAID has spent on education in Afghanistan as of March 2015.

Sopko warned that Afghan officials under former President Hamid Karzai may have cheated both their own government and international donors, notably USAID and the World Bank. Those Karzai appointees allegedly lied about how many schools were functioning in the country so that they could obtain more funding. Sopko noted that the new Afghan ministers of education and of higher education have told lawmakers that their predecessors routinely falsified statistics. The ministers said that as a result, "insecure parts of the country" -- those most affected by the Taliban insurgency -- now lack functioning schools.

"These allegations suggest that U.S. and other donors may have paid for schools that students do not attend and for the salaries of teachers who do not teach," Sopko wrote in his June 11 letter to acting USAID Administrator Alfonso Lenhardt. (Read the letter here.)

The inspector general asked USAID to respond by June 30 to a series of questions about how it is investigating whether Afghan officials lied to it and how it can avoid the problem of funding so-called ghost schools in the future. Sopko noted that his office, SIGAR, is already auditing U.S. spending on education in Afghanistan, but said he believes these allegations "call for immediate attention."

Larry Sampler, assistant to USAID's director on Afghanistan and Pakistan, told HuffPost in a statement that the agency is talking to the Afghan government about why the new ministers made those claims. He added that the agency is working with the Afghan education ministry to make its data more reliable.

"USAID is working with the new Government of Afghanistan to build a comprehensive, nationwide education system that will endure long after reductions in international assistance," Sampler said.

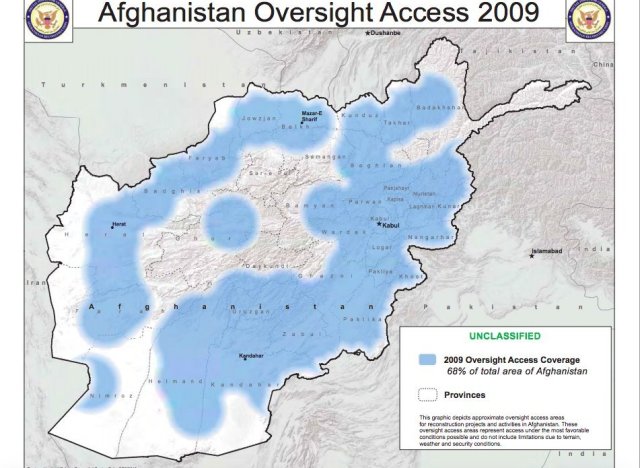

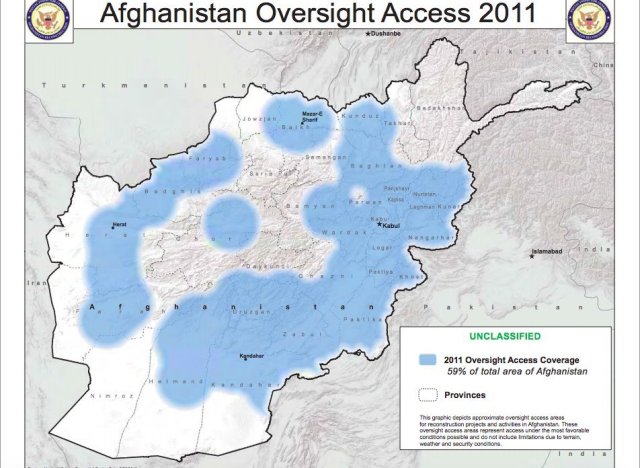

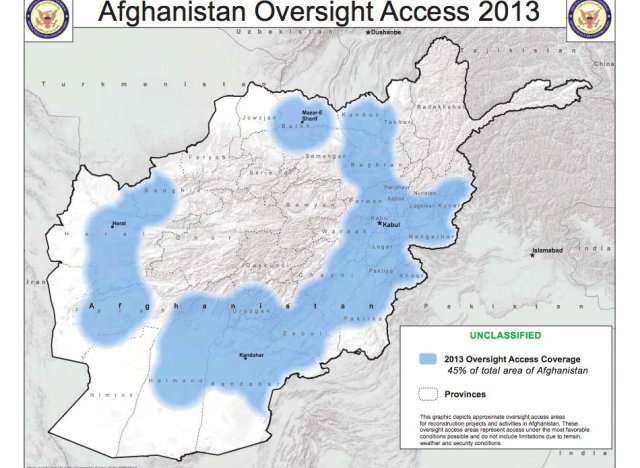

SIGAR's latest warning on how uncertain progress has been in Afghanistan highlights the American reliance on Afghan officials to measure how well U.S. taxpayer dollars are being used there. That dependence will only increase as U.S. troops withdraw from the country, a process that President Barack Obama recently slowed down but that he has committed to completing by the end of 2016. With fewer U.S. officials on the ground and fewer U.S. troops available to protect them should they try to travel around the country, oversight is expected to become significantly worse. The maps below, provided to The Huffington Post by SIGAR, show how the U.S. capacity to measure its impact in Afghanistan plummeted between 2009 and 2013.

Updated maps have yet to be completed, but asked about the oversight situation on Thursday, a U.S. official speaking on background was clearly pessimistic.

"The bubbles on that map are really Swiss cheese now," the official said. The U.S. civilian presence in two major Afghan cities -- Kandahar and Mazar-i-Sharif -- is winding down within a week, according to the official, and the same may happen in the city of Jalalabad.

"U.S. personnel can only really go around in Kabul, and for the most part, there is no travel outside of the green zone," the official told HuffPost.

Troubling as the new allegations and risk of future losses are for U.S. taxpayers, they are likely even more upsetting for the Afghan public. Government mismanagement of schools complicates what is already a difficult journey for young Afghans to get an education. The simple act of attending school has become dangerous again in the face of the Taliban insurgency. A school was hit by a rocket attack earlier this month, killing three, and many families are choosing to keep their children at home rather than risk sending them to a potential target.

In that context, building faith in the government's capacity to run and secure a USAID-assisted eduction system is even more important. Expectations in Afghanistan are high because USAID has claimed a certain success post-invasion, saying that it has helped boost school enrollment from under a million students (the overwhelming majority of whom were male) to more than 8 million (including 2.5 million girls).

But those figures were based on the possibly doctored Afghan Ministry of Education figures. With Washington having vowed time and again that it would not abandon Afghanistan's vulnerable populations, particularly women, the challenge for USAID and other U.S. officials is to show they can effectively measure what they are accomplishing in the still-fragile country.