The debate over vaccine safety rages on, with no clear end in sight. On the one side is a medical establishment made up of hundreds of thousands of doctors, researchers, infectious disease specialists, vaccine manufacturers, the FDA, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and our government, who all insist that vaccines are safe and everyone should comply with the standard recommended vaccine schedule. On the other side is a growing number of parents, and a small but growing number of physicians, who are questioning vaccine safety. Caught in the middle are the 5 million couples who have a baby every year and are faced with the decision of whether or not to vaccinate.

I've been studying vaccines for over 16 years, ever since my first child was born. I was in medical school at Georgetown at the time, and since I wasn't learning much about vaccines there (besides "vaccines good, diseases bad"), I decided to educate myself on all the pros and cons of vaccines. I wanted to know what my son was being given and what the benefits and risks were. After studying everything I could get my hands on, I came to the conclusion that vaccines are effective and generally safe for most children, but that there is a small risk of a serious reaction. This may not seem like any great revelation, as most people agree that vaccines do work (although not 100%, and in some cases as low as 85%), and that most children seem to handle them just fine without harmful effects.

The reason I viewed my conclusion as significant was that back in the 1990s, the party line within the medical community was that vaccines do not cause severe reactions. Reports of seizures, encephalitis, autoimmune reactions, bleeding disorders, and neurological injuries were just coincidence. Vaccines can't cause that. Now we know differently, and the medical establishment has acknowledged that such reactions can be attributed to vaccines (just read any vaccine product insert). So the party line has changed to the opinion that such severe reactions are so rare that the general population doesn't (and shouldn't) need to worry about them. But every parent is still going to worry that their one individual baby is going to be one of those statistics. And that's an understandable concern.

Enter the autism debate, spurred by the research of Dr. Andrew Wakefield (as we all watched on Dateline Sunday night). Dr. Wakefield certainly wasn't the first person to suspect a link between vaccines and autism, but he was the first doctor to get a study published in a mainstream medical journal that showed a possible link between the MMR vaccine, inflammatory bowel disease, and autism. His research has come under vigorous attack and has been almost universally dismissed by the mainstream medical community. I think Matt Lauer portrayed this debate in a fair manner, allowing Dr. Wakefield to share his ideas and research and answer some of the primary criticisms of his work. I could go back and forth all day long about who is right and who is wrong and what we know and don't know about the MMR vaccine (and vaccines in general) and autism, but that isn't the purpose of this blog. My goal is to help parents decide what to do.

Ultimately, I believe the vaccine/autism question cannot be answered until a very large, prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study is done that compares the rate of autism in a very large group of vaccinated versus unvaccinated children. That type of study is the gold standard of medical research, and until that study is done this issue cannot be put to rest for many parents; there will continue to be doubt in many parents' minds about the safety of vaccines. I know that there are dozens of studies that show there is probably no link between vaccines and autism, and virtually every doctor, government official, and vaccine manufacturer is very quick to point that out. But parents just don't believe it. And they won't believe it until the type of large study I describe above is done. But that research is many years away. Millions of parents need to know what to do with their babies now. Here is my solution: vaccinate, but do so in a manner that lowers the risks.

Allow me to preempt any uproar before I continue. First, some people believe that there is a link between vaccines and autism, and that even careful vaccination may be risky. If you are such a person, don't vaccinate. I know there are ten of thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, of families that believe their child's autism was (at least in part) triggered by vaccines, and my heart goes out to each and every one of you. I have several hundred such families in my own practice. I don't push vaccines on anybody, and I am completely happy to respect any family's decision not to vaccinate. Any new parent who believes there is a link and is not comfortable with vaccinating shouldn't do so. And they should be fully informed about what the disease risks are if they don't vaccinate.

Second, most doctors believe that we shouldn't offer alternative vaccine schedules. There should be only one schedule that every family should comply with. Offering options plays into parents' fears and doesn't set a good precedent. I believe that such closed-mindedness leads to lower vaccination rates. Most parents do comply with the regular schedule because they feel comfortable with it. But many of those who refuse to vaccinate in that manner will accept vaccines if they are given more gradually. If doctors would just be willing to work with these parents, the government and the medical community wouldn't have to worry about diseases running rampant through our nation again.

This is a little pet peeve of mine, and this closed-minded attitude really came across when watching Dr. Offit's comments, and Brian Deer's, for that matter. They are so certain they are right, and that vaccines are completely safe, case closed. Whereas, Dr. Wakefield admits that he doesn't know whether he's right or wrong regarding MMR and autism, but he believes we should keep looking. He's open minded, and open to the possibility he may be wrong in the long run. He just wants to make sure. And he's not alone. Dr. Healy (former director of the National Institutes of Health, for crying out loud!) agrees -- more research needs to be done.

So how can parents vaccinate their baby in a manner that lowers the risks of reactions? Let's talk about the MMR vaccine first, since that was the focus of the Dateline piece. The MMR is normally given at the 12-month checkup, and 5 million families will have to decide this year what to do. Here are the options: 1.) Get the vaccine, 2.) Wait on the vaccine until your infant is a little older, 3.) Wait until the separate measles, mumps, and rubella vaccines come out again in 2011 and then get those shots one-at-a-time, or 4.) Skip the MMR altogether.

Sounds simple, right? Well, it's not. It's confusing as hell for parents who are torn over what to do. Here are some things to consider. If you have a child with autism already, then as a precaution I suggest you skip the MMR vaccine for any future children you have (and don't get the MMR booster at age 5 for your child with autism). Although the science is overwhelmingly in favor of no link between MMR and autism, until a large-scale study is done in the manner I suggest above to really prove there is no link (or as close to "proof" as we can come), parents with autism in their family already should be cautious. But what about the other 99% of families without a child with autism? If your child has any of the risk factors associated with autism, such as severe food allergies, chronic diarrhea, any form of early developmental delay, or a strong family history of autoimmune disease (as revealed this month in Pediatrics), the MMR should be at least postponed until these problems resolve. Again, no science, just a precaution.

But most infants don't fall into either of these categories; they are perfectly healthy. What should they do? Any toddler who is entering daycare and will be around a lot of other babies would be at a higher risk of being part of a measles, mumps, or rubella outbreak, or of starting one. The MMR vaccine may be more important for such a toddler. Families traveling out of the country would also have a higher risk of an unvaccinated infant catching measles, mumps, or rubella. An infant who is not going to be in early childcare, on the other hand, would have a lower risk. Delaying or skipping the vaccine in such a child would pose little risk to those around him. What is the risk of catching one of these diseases if you skip the MMR? There are about 150 cases of measles, 250 cases of mumps, and 10 cases of rubella reported every year in the United States.

There are probably more cases than these that go unrecognized, but these are the numbers we know for sure. Add them up and you get about 410 yearly cases out of the approximately 50 million U.S. children age 10 and under. That's a 1 in 120,000 chance every year that your unvaccinated child will catch one of these three illnesses. What about fatality risk? Mumps isn't fatal (although it can cause serious health consequences for teens and adults), Rubella is harmless to children (but cause birth defects if a pregnant mother catches it from a child), and measles is fatal in about 1 in 500 to 1 in 1000 cases. So, these are the risks if you go without MMR, according to today's statistics. If more and more parents refuse the MMR, these diseases will increase, as will the risks. Right how, enough parents are vaccinating to keep these diseases at low levels. But will that change?

Is there a safer way to get the MMR vaccine? There used to be. Up until 2008, the company that makes the MMR vaccine (Merck) also made separate measles, mumps, and rubella vaccines. Parents could choose to get these shots one at a time. The logic behind such a choice was that the MMR vaccine (and Chickenpox vaccine as well) are live virus vaccines; these shots are designed to mimic a natural infection and allow the immune system to develop protection. Well, getting the MMR and Chickenpox vaccines all on the same day (as it is recommended on the regular schedule) is a far cry from how children would be exposed to these illnesses back when they were common. Children never caught all four of these diseases at once - they were spread out over a few years, allowing the immune system to react to and handle each one individually. Vaccinating in a similar manner more naturally mimics how a child would be exposed to such diseases back when these were common. Getting only one live-virus vaccine at a time could theoretically be safer. However, Merck stopped making the separate vaccines in 2008. So, that choice doesn't exist for parents right now. But good news: Merck announced they will once again resume production to have these separate vaccines available again in 2011. So, parents have to decide whether to go with the full MMR now or wait until the separate vaccines come out again.

There are so many factors to consider here, and every family has to make a choice. Someday we will have that prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to help give parents some definitive guidance. When will that day be? As we speak, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is putting together a plan to study whether or not such a large-scale research project is even feasible. They are studying whether or not they should do the study, so to speak. If they decide it is feasible, then they will design the study and undertake it. I believe such a study is feasible, with the exception of the "randomized" aspect. To make the study randomized, children would need to be assigned to either the vaccinated group or the unvaccinated group without the parents knowing. That's just not going to fly. The unvaccinated group will likely need to be children whose parents volunteer for it. And that not only eliminates the randomization, it also throws a wrench into the "double-blindness" of the study in that the parents will not be able to contribute their observations and opinions about their child's health, because they know whether or not their child got the vaccines, and that may skew their observations and their answers to questions. But the researchers who are studying the children will be blinded to their vaccination status, and that will have to be good enough. We won't have any results to work with for as many as five years, and possibly longer, if they even do the study at all. So parents are left with looking at all the research we have available now, considering their own infant's situation in life, and making a decision.

What about the other 11 childhood vaccines? Most research shows no link to autism, but again we don't have that large scale placebo-controlled study. So, is there a way to vaccinate that lowers the risks? Yes. Parents can get fewer vaccines at each visit and spread the shots out over more years. Here's how I do this in my practice. I skip the Hepatitis B vaccine in the hospital (unless the baby is sexually active or is going to share IV drug needles with another baby). At two months I begin vaccines, but I limit a baby to 2 shots at a time at each visit, instead of the recommended 6 vaccines. I give babies protection from the potentially serious and life-threatening diseases (whooping cough, rotavirus, and two forms of meningitis) in a timely manner. Since the flu kills about 20 infants each year, that shot could also be included on the list of what's important. What I skip is Hep B and Polio, since those two diseases don't pose any risk to babies in the United States. I do eventually begin working in polio vaccine but not until I'm done with the other more important ones. And I save Hep B until school age. I believe spreading the shots out in this manner reduces the risk of having a severe reaction and avoids overloading babies with too many chemical ingredients (especially aluminum) at one time. My critics are very quick to point out that there is no research to support this type of approach, and I would be very quick to agree with them. This is just a precautionary way to help worried parents feel more comfortable with vaccines. Anti-vaccine critics will also point out that there's no guarantee that my approach is safer; an infant can have a severe reaction even when only one vaccine is given. This is true. But I believe my approach is a good compromise.

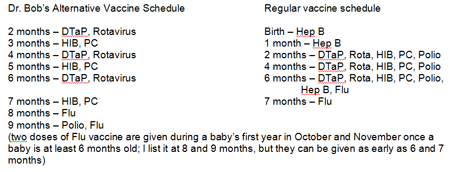

Here is my first-year schedule compared to the regular one:

As you can see, my schedule provides the vaccines for only the potentially life-threatening illnesses during the first year, and provides them in a manner that doesn't overload a baby with too many shots on the same day (notice that at six months as many as 7 separate vaccines can be given all on the same day with the regular schedule). My alternative is a way for worried parents, who might be considering skipping vaccines altogether, to vaccinate.

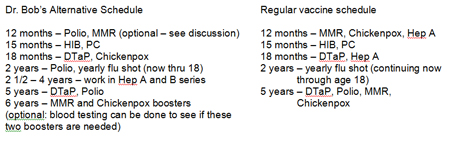

What does the rest of my alternative schedule look like?

Note: there are more vaccines during the teen years as well: Tdap, Meningococcal, HPV vaccine.

I also offer another schedule in my book that I call Dr. Bob's Selective Vaccine Schedule. It only provides the most important vaccines and skips those that are less important (such as for diseases that are usually mild or that don't exist in the U.S. or during young childhood).

Deciding whether or not to vaccinate isn't an easy choice for parents who are worried about vaccines. Realize, however, that this isn't an all-or-nothing decision. There are 12 different vaccines, and you have 12 different decisions to make. You can pick and choose vaccines. You study the diseases and decide which ones pose the greatest risk to your child. You also study how each vaccine is made, what the ingredients are, and what the possible side effects may be. You put all of this information together and make a decision. If you aren't sure what you want to do, then don't do anything until you are sure.

There are so many confused parents out there who aren't sure what to do. Get educated, read a few books, talk to your doctor, and if you are still confused, join my Parent's Forum on www.TheVaccineBook.com and shoot me a question. I'm on there everyday answering questions from parents all over the world. I look forward to interacting with you.