News that former New York Governor Mario Cuomo passed away on New Year's Day brings forth memories of when I was working for Texas Governor Ann Richards and met him at a National Governors' Association meeting in 1992. That year, the country was in a recession that had increased the child poverty rate to 22.3 percent. To his fellow governors, Cuomo spoke eloquently and passionately about the needs of those families hard hit by the economic downturn and the role of government in addressing the crisis.

Just a few weeks later, Cuomo gave the nominating speech for presidential candidate Bill Clinton at the Democratic National Convention and he spoke specifically about the recession's devastating impact on children:

A million children a year leaving school for the mean streets, surrounded by prostitutes and drug dealers, by violence and degradation.

Some of them growing up familiar with the sound of gunfire before they've ever heard an orchestra . . . becoming young adults, only to be instructed by the powerful evidence of their surroundings that there is little hope for them - even in America.

Nearly a whole generation surrendered in despair - to drugs, to having children while they're still children, to hopelessness.

How did it happen, here, in the most powerful nation in the world?

It's a terrible tragedy. Not only for our children, but for all of America.

Cuomo was right to be concerned about the plight of children during the recession and, although that was over 22 years ago and children have made some important advances in recent years, much of his speech still rings true today.

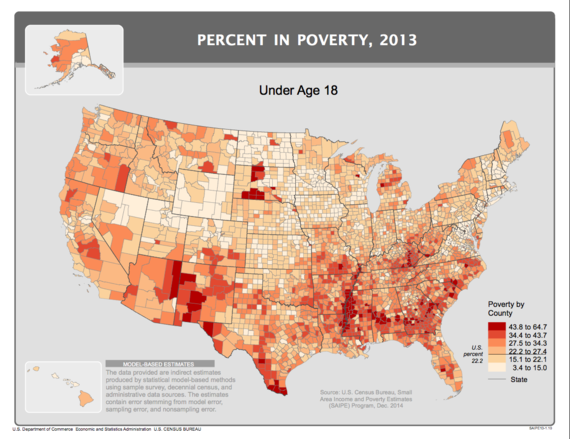

In fact, on the back end of the most recent recession, 21.8 percent of children lived in poverty in 2012, a record 2.5 million children were homeless, and nearly 16 million children live in food-insecure households.

We can and must do better.

One challenge is both demographic and geographic. According to Steve Murdock, former Census Bureau Director in the Bush Administration, and his co-authors Michael Cline and Mary Zey, kids in the Southwest region (defined as the seven states of California, Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, Nevada, Utah, and Colorado) are "increasingly an important center of growth in the number of children, particularly minority children, in the United States."

The seven states accounted for:

- 90 percent of the 2000-2010 increase in the nation's child population;

- More than half of America's Hispanic child population;

- Nearly one-third of American Indian and Alaskan Native children in the United States; and,

- More than 40 percent of America's Asian child population.

As such, it is a place that holds the key for much of our nation's future.

Unfortunately, the Southwest is not faring well by its children. Using over 16 different indicators, the Annie E. Casey Foundation (AECF)'s 2014 KIDS COUNT Data Book ranked the 50 states by child outcomes and found the five southwestern border states of California (40th), Texas (43rd), Arizona (46th), Nevada (48th), and New Mexico (49th) were among the 11 worst states based on key child indicators, such as child poverty, infant mortality, and high school graduation rates.

In addition to these five southwestern states, the other states that rank among the worst were the six southeastern states of Arkansas (41st), Georgia (42nd), Alabama (44th), South Carolina (45th), Louisiana (47th), and Mississippi (50th).

There is one common theme among these 11 states that plays a major role in their poor performance: they all invest fewer resources in their children than the national average.

The increasing number of children and the problems they face in the Southwest [and the South] might have a better chance at alleviation if states within the region strongly supported public programs designed to benefit children, such as social services, educational institutions, income support programs, and health programs. But states in [these regions] tend not to support such programs at the same levels found in most other states.

Money (or more accurately, the lack thereof) clearly matters.

A challenge related to the problem of geography is that of political leadership. The children of the Southwest and Southeast cannot make progress if their elected officials refuse to recognize that children are their most important resource.

My high school classmate, friend, and writer, Richard Parker, highlights this problem in his new book entitled Lone Star Nation. He writes about the importance of education and the promise of Texas to lead the nation in future growth based on its "Fountain of Youth," but only if its political leaders change course by making investments, rather than budget cuts, to its public schools, higher education, water, and public infrastructure. Parker says:

If more of the new majority in Texas don't go to college and increase their earning power, consumer spending will fall. The ability to sustain the tax base, particularly property taxes, will be in jeopardy. This will affect not just Hispanics; it will impact everyone, regardless of ethnicity or age, individuals, businesses and institutions - private and public - alike. The entire Texas boom, which could power the American economy through the rest of the century, would stutter and stall.

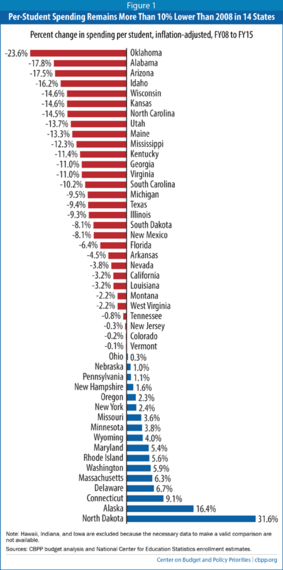

Parker argues that we live in a global economy and this dictates we ensure the next generation is highly educated in order to remain competitive. Unfortunately, Texas cut public education spending by over $5 billion in 2011. These cuts were devastating and exacerbated funding inequities so greatly that their school finance system was recently ruled to be inadequate and unconstitutional.

But, this declining investment in kids is not just a Texas problem. According to data from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, "At least 30 states are providing less funding per student for the 2014-15 school year than they did before the recession hit. Fourteen of these states have cut per-student funding by more than 10 percent." This is the case for all the states in the Southwest and Southeast, as they were already below the national average in support of public education before the recession even began.

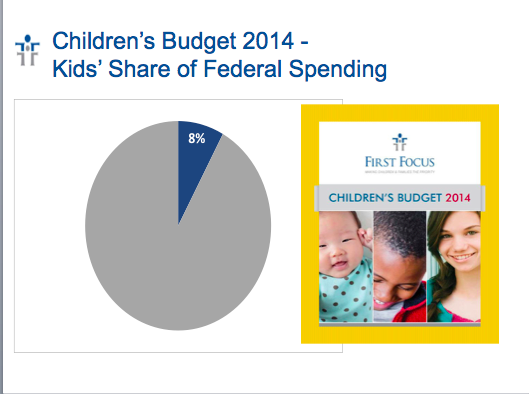

At the national level, dedicated investments in our nation's children is also in decline. A report by First Focus entitled Children's Budget finds that federal support for children's programs has dropped by 14 percent after adjusting for inflation since 2010 and that overall spending on children now constitutes just 8 percent of the federal budget.

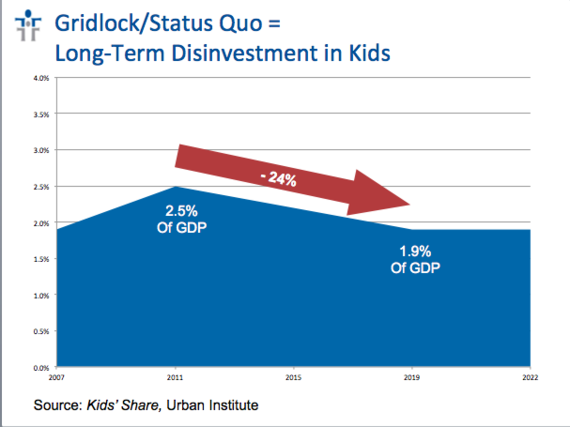

And, Urban Institute's report, Kids' Share 2014, estimates that, if policy changes are not enacted by the President and Congress in the near future, the share of federal investments committed to children will continue to decline by about one-fifth of both the share of the federal budget and the economy over the next decade.

In reviewing the report's data, Anna Bernasek of Newsweek notes that if this trend continues, "the federal government soon will be spending more on interest payments on the debt than on children."

And, as the Kids' Share report concludes:

Without adequately funded education, nutrition, housing, early education and care, and other basic supports, the foundation of children's well-being is at risk. When children grow up without adequate supports, they are less able to support themselves and to contribute to economic growth as adults. . . . A continuous decline in federal support for children over the next decade bodes poorly for their future or the future of the nation.

A related challenge is demographic and intergenerational. According to Murdock, Cline, and Zey:

What is also evident is that the children of today will not be successful without substantial assistance from an older population that now and in the future is likely to possess superior economic resources. . . .

The major question raised . . . is: Will the United States' adult population (through elections, taxes and other factors) support the youth who are racially and culturally different from themselves and their children or will they perpetuate a dual class education and economic structure which has dominated many areas in the United States, including many areas in the Southwest?

How that question is answered will be critical to our nation's future. William Frey, author of Diversity Explosion: How New Racial Demographics Are Remaking America writes:

. . . a growing diverse, globally connected minority population will be absolutely necessary to infuse the aging American labor force with vitality and to sustain populations in many parts of the country that are facing population declines. Rather than being feared, America's new diversity - poised to reinvigorate the country at a time when other developed nations are facing advanced aging and population loss - can be celebrated.

In 12 U.S. states (Hawaii, New Mexico, California, Texas, Nevada, Arizona, Florida, Maryland, Georgia, New Jersey, Mississippi, and New York), the Census Bureau estimates that minority children under the age of 10 are in the majority. And, enrollment in our nation's public schools has also become majority-minority, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

"Yet, as Frey explains, "this youth-driven diversity surge is also creating a 'cultural generation gap' between the diverse youth population and the growing, older, still predominately white population."

Frey points to states where the difference between the percentage of seniors and children who are white as places where there may be greater tension between the generations and competition for resources allocated to children and the elderly and where children may be significant losers.

Murdock, Cline, and Zey share this concern and point to research by James Poterba that found "in communities with large proportions of elderly residents there were significantly lower per-capita educational spending, especially when the children were of a different race from that of their elders."

According to Frey, among the states, Arizona leads the way with a "cultural generation gap" of 41 percent (83 percent of seniors and 42 percent of children were white). So, how is Arizona doing by its children?

The Arizona Daily Sun has documented how budget cuts to child protective services in Arizona caused child welfare caseloads to soar and reports of child abuse to be ignored, cuts to public education had resulted in per-public spending during the recession to decline by 24 percent, and reductions in state funding to higher education to be $300 million below pre-recession levels.

In addition, Arizona is the only state in the country to no longer provide health insurance coverage to children under the Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP), as it let the program expire at the close of 2013 and so now has the 2nd highest uninsured rate for children in the country.

And, it is a state that enacted some of the some most stringent anti-immigration legislation, SB170, in the country and banned schools from offering courses such as Mexican-American studies that federal courts have partially overturned.

As Murdock, Cline, and Zey said:

The future of areas such as the Southwest, and of the Nation as a whole, may be markedly affected by the extent to which its older populations are willing to step forward to support its increasingly diverse youth.

What is clearly evident is that the future of the Southwest and the United States as a whole is increasingly tied to the future of its minority populations. . . . Whether the nation prospers or struggles to maintain its current standard of living and whether it can compete internationally will depend on how well the diverse children such as those in the Southwest do. Ultimately, how well these children do will be how well America will do.

To ensure a strong future America, we must overcome the forces and ignorance and prejudice that are cutting - rather than investing - in education and our nation's children. New York Times columnist Eduardo Porter adds:

If the next generation is going to be handed the bill for our budget deficits, we might as well make the investments needed to help it bear the burden. So far, we seem on track to bequeath our children a double whammy: a mountain of debt and substantial program cuts that will undermine their ability to shoulder it when their time comes.

Ronald Brownstein has also written extensively about this generational political challenge (see, for example, here, here, here, and here).

The nation faces the risk of sustained political tension between its racially diverse, Democratic-leaning youth population and its predominantly white, Republican-trending senior population -- what I've called the Brown and the Gray. Although it's rarely discussed now, both groups share an interest in equipping the young to obtain middle-class jobs that will generate the tax base to support a decent safety net for the old.

Since kids do not vote, we need an informed electorate that will translate its long-standing support for children into votes. This requires that advocates for children, including parents, grandparents, educators, etc., work together to build a grassroots movement to educate the public and demand from policymakers that they put forth a real policy agenda - and not just lip service - that would improve child well-being and then hold those policymakers accountable for real results.

Imagine how different things for children might be if politicians were the ones to lose their jobs for failing to improve education, reduce child poverty, etc. What is needed is a focus on the needs of children before it is too late.

Former Republican House Majority Leader Eric Cantor apparently agrees that the new 114th Congress should make children a focus of its agenda. He writes:

As the new Congress convenes, I hope the president and members from both parties will keep one number in mind: 8,053,000. That is an estimate of the number of new Americans expected to be born between now and the end of this Congress and President Obama's second term two years from now. . . . The future of those 8,053,000 little boys and girls deserve to have the two years of this Congress focused on them and not the next election.

According to the Census Bureau, half of these will be minority births and about half will be white. We should value each and every one of them.

I remember understanding this for the first time so clearly when, in that same 1992 speech, Cuomo said:

They are not my children, perhaps. Perhaps they are not your children, either. But, they are our children. We should love them.

But even if could choose not to love them, we would still need them to be sound and productive. Because they are the nation's future.