Small·ball [smawl bawl] --noun. In the sport of baseball, small-ball is an informal and colloquial term for an offensive strategy in which the batting team emphasizes placing runners on base and then advancing them into position to score a run in a deliberate, methodical way.

I've been thinking about the venture capital asset class lately. Of course, working at Silicon Valley Bank, this is essentially unavoidable. Looking over the sweep of recent history 30 years or so, it jumps out that the Internet investment environment has affected the sector in fundamental and peculiar ways. Clearly not a blinding insight, but we're not referring to the outsized returns of those mid-90s vintages.

I've sometimes thought of the industry as a bunch of bettors standing around a roulette wheel. There are enough people and enough money to bet on each number. On every spin of the wheel, most will lose their bet, but one person will also win a 35:1 payout. From an economic perspective, it has been hugely beneficial to have all these bettors willing to lose all that money because the 35:1 winners gave us Intel, Microsoft, Seagate, Cisco, Netscape, Amazon, Google and...well it is a very long list. The millions of jobs created by this activity are very well-documented.

The nature of those bets has changed over the years with advances in the basic sciences, communications and computing technologies. They also changed as the technologies promoted by venture-backed firms were infused into every aspect of the economy and society. So we went from integrated circuits and disk drives to sequenced DNA, social networks and cleantech. One primary use of the Internet today is advertising and retail sales. Dozens (perhaps hundreds) of companies have been founded to make that advertising more efficient in selling products to that elusive long tail.

The side effect of all this is that companies can now be created on the cheap. The combined effect of the low investment hurdle to get a service to market and the psychological shadow of the tens of billions lost during and after the Internet bubble might have made VC investors too risk averse. They too often focus on what we call derivative business models. For example, build a game to run on Facebook; then build a tool to help game players optimize their strategy. Before you know it, there are several firms focused on secondary market trading of avatar accessories. Once you get to third and fourth order derivatives, it becomes a very long-tail market. These may be small dollar bets, but they also have limited upside.

What that means in the roulette game metaphor is that the size and risk of the bets has changed. Instead of betting on numbers, some are moving to even money bets on red-black or odd-even with smaller amounts deployed. This is evident in the lack of seed investments in recent years with more money assigned to larger, stable later-stage companies where the downside is smaller and the upside is limited.

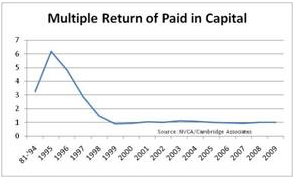

The outsized bets on companies that would have been public in another era are additional evidence. We think this investor behavior is one aspect of the poor performance for the asset class in recent years with median returns dropping to around one time invested capital. (See graph) Maybe the funds have been playing small-ball, rather than swinging for the fences.

The outsized bets on companies that would have been public in another era are additional evidence. We think this investor behavior is one aspect of the poor performance for the asset class in recent years with median returns dropping to around one time invested capital. (See graph) Maybe the funds have been playing small-ball, rather than swinging for the fences.

It is not unusual to run into teams of three or four young engineers who are creating a new app for the iPhone, Facebook or some other platform. They will build this up until some app aggregator buys their product or service for $1 million. The three partners split the proceeds and then start the process again. If you ask them about taking in some VC money and building a real company, they will back away. There are a couple reasons behind this psychology in my view. First, they see the potentially higher payout as too distant. This is supported by SVB's own studies showing the vast majority of recent VC exits have been companies founded close to 10 years ago. Second, they see too high a probability of a zero payout after that 10-year wait. This, too, is supported by the data as median VC 10-year returns are now a negative 3.7 percent.

Will the industry shift back to higher risk investments to capture the excess returns of the glory years? It may be difficult. One of the odd attributes of VC fund management is that the more successful you are, the more likely you will be successful in the future. This is in sharp contrast to equity or bond funds where beating the averages long-term is very unusual. The reason Peter Lynch was so well known is that he outperformed for so many years and that in itself was a six-sigma event. For venture funds it is more common for managers to outperform year after year because of the information advantage gained from success.

A top performing fund after some time will not only attract lots of new LP money (which puts future returns at risk), but it will attract the best deals. If you are an entrepreneur and you are going to take venture money, you want to get it from the known, quality firms. Some of these firms probably get to see every transaction in the marketplace. That selection advantage does not exist in public-market fund management because anyone can buy any stock or bond on any day. That record of success and its benefits alone would tend to make fund managers risk averse as a couple of bad vintages could jeopardize the long-term benefit.

So it seems that future home runs will likely come from new funds. Unfortunately, the ability for new managers to attract LP dollars is fading. Every LP I've ever met with has said convincingly that they only invest in the top quartile funds. (We often wonder where the other 75 percent get their money.) Statistically, the pace of new fund creation follows the dispersion of returns with a two-year lag. So as dispersion reaches extremes, LPs will sponsor new funds, in effect chasing the returns they saw a couple years ago. Given recent performance LPs may be more reluctant to take a flyer on a new manager.

Into this breach steps the super angel. These are successful entrepreneurs who want to keep their hand in the game and have $50 to $100 million to deploy. In our view, these are the investors most likely to make the types of bets the funds were making back in 1996-97. They are not newly-minted MBAs with little operating experience seeking a career, but savvy battle hardened gamblers looking to change the world. They may also have an information advantage that is different from the successful mega-funds, but potentially more valuable.

As all of these trends continue to rile the industry, there is one element in which we have complete confidence: Entrepreneurs will continue to innovate whether there is funding or not. They cannot help themselves. And that is a very good thing for all of us.