Thi Quang Lam, a former general in the South Vietnamese army, is the author of The Twenty-five Year Century: A South Vietnamese General Remembers the Indochina War to the Fall of Saigon and most recently, Hell in An Loc: The 1972 Easter Invasion and the Battle That Saved South Vietnam. He also happens to be my father. Below is a Q&A I conducted with him on issues related to contemporary Vietnam and its growing unrest, spurred in large part by China's aggression and Hanoi's muted response.

What has China been doing that got the Vietnamese so upset?

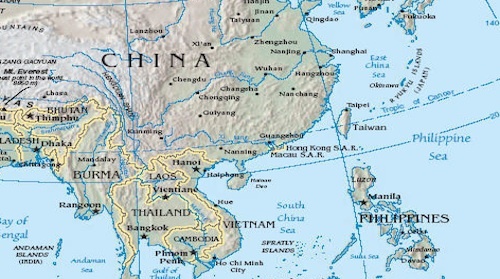

The deployment of a Chinese oil rig within Vietnam's territorial waters about 120 nautical miles east of Vietnam's Quang Ngai province early in May added to a persistent pattern of Chinese aggression in the Asia Pacific, spanning four decades. It includes the occupation of the Paracel Islands in 1974 and of the Spratly archipelago in 1979. The acquisition of 12,000 square kilometers of territorial waters in the Gulf of Tonkin conceded by Hanoi under a pact signed in 2000. This is not to mention China's claims on field rich in natural gas near the Natuna Islands, 400 miles northeast of Sumatra, Indonesia, and its dispute with Japan over the Senkaku islands in the East China Sea.

Also, the Chinese navy frequently killed or arrested Vietnamese fishermen operating within Vietnam's territorial waters. These incidents added to a consistent pattern of Chinese expansionism.

You've said in the past that the Vietnamese Communist regime is in a bit of a quandary, why?

Vietnam is caught in an insoluble political dilemma. It is a lose-lose situation because the continuous erosion of the nation's territorial integrity could trigger a popular uprising, and even a revolt within the army that had fought a bloody border war against China in 1979 and has grown increasingly frustrated with the party leadership's subservience to Vietnam's historic enemy to the north.

There is a saying in Vietnam that "if Vietnamese communist leaders follow China, they will lose the country. But if they side with the U.S. they will lose the party." This is generally correct, because the influx of new ideas, technology and money would accelerate a democratization that could ultimately bring down the corrupt and unpopular regime. Although another Vietnamese saying, nuoc mat, nha tan (if we lose the country, the house disappears), gets closer to the truth: if Vietnam's communist leaders lose the country due to China's expansionism, then they will also lose the party, for the simple reason that the party can't exist in a vacuum.

In the final analysis, embracing the United States seems to be Vietnam's best option in dealing with Chinese aggression, as the U.S. is the only superpower that can counter China's expansionist policy. This would, however, require Vietnam to implement sweeping reforms, because the U.S. government so far has been reluctant to align itself militarily with the country due its poor human rights record.

Why should the US get involved?

The United States is once again in a position to exert its leverage in this strategic area of the world. By conditioning the granting of military support on the improvement of Hanoi's human rights record, the United States could help ensure a free and democratic Vietnam that would be better able to stand up to Chinese expansionism.

Secretary of State Hillary Clinton affirmed during the ASEAN Regional Forum in Hanoi in July 2010 that it is America's "national interest" [in the region] and calling for a regional solution.

On a visit to Beijing in July in 2011, Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman Admiral Mike Mullen restated Washington's determination to maintain a long-term presence in the region. He also expressed concern that barring a resolution, the crisis could trigger a regional conflict with unpredictable consequences.

Backing up these statements have been U.S. naval activities in the area; including joint exercises with the navies of South Korea, Vietnam and the Philippines, the latter two countries being actively involved in territorial disputes with China over the oil-rich Spratly islands.

Despite the fast-changing geo-political allegiances in the Asia-Pacific region is the fact that the post World War II policy of "containment" remains a popular ploy in today's global political chess game. Vietnam has thus regained its strategic value in U.S. eyes as a missing link in the containment scheme and a counter-balance to the increasing threat of Chinese expansionism. And Vietnam appears only too willing to accommodate.

In a sense the United States -- without firing a shot -- is closer than ever to realizing its original goal of an independent and non-Communist Vietnam for which 58,000 Americans and hundreds of thousands South Vietnamese have given their lives.

Given the volatility in the area, would more US involvement risks an escalation of conflict that could spark a war?

When it comes to geopolitics, especially in the South China Sea, there's a time for détente and then there's a time for deterrence. The war over natural resources and energy has only just begun and is predicted to intensify in the coming decades. Countries ill equipped to defend their interests will be at a great disadvantage in the long run.

History teaches that appeasement without teeth only encourages aggression. Richard Nixon, who possibly knew China better than any other US president noted that "Detente without deterrence leads to appeasement, and deterrence without detente leads to unnecessary confrontation."

But because China's autocratic communist regime knows only the language of force when it comes to the South China Sea, and because of the high stakes involved in the strategic Western Pacific region, it may be better to threaten deterrence -- even at the cost of detente -- than to offer detente without the will for deterrence.

Vietnamese protestors on the street of Hanoi in March 2012, demanding for a new draft in the constitution that includes human rights.What is your reading of the current situation in Vietnam?

Vietnamese protestors on the street of Hanoi in March 2012, demanding for a new draft in the constitution that includes human rights.What is your reading of the current situation in Vietnam?

The Vietnamese Communist Party (VCP) is not ready to capitulate, because the greater it feels threatened, the stronger it cracks down on dissidents. Bloggers demanding freedom and democracy are slapped with long-term prison verdicts. The police and the cong an (or public security agents) brutally beat up and/or arrest the farmers protesting against massive land grabs or demonstrators against rampant corruption and the government inability to counter China's aggression in the South China Sea (known in Vietnam as Bien Dong, or Eastern Sea).

Protestors condemn the communist party and demand human rights in Hanoi.

In the course of human history, violence, even terror, is often used to quell political unrest. Toward the end of the 18th century, for example, Maximilien de Robespierre, a leading figure of the French Revolution, had sent thousands of French to their death under the guillotine, in order to quell the post-revolution chaos and attempted restoration of the French monarchy. It is significant that Robespierre considered virtue and terror as the two pillars of the revolution.

"If the basis of popular government in peacetime," Robespierre said, "is virtue, the basis of popular government during a revolution is both virtue and terror; virtue without terror is baneful; terror without virtue is powerless."

Political scientists assert that the communist system survives only if it can control: a) the stomach: b) the movement; and c) the mind of the people."

In Vietnam today, the old "ho khau" (or food rationing) system no longer exists; the people can move relatively freely within the country; but the control of the mind is being shattered by the tremendous advances in the information technology.

Recent developments in Vietnam have proved Robespierre right. The VCP, obviously, is not known for its virtue, and without virtue, according to Robespierre, terror is powerless.

Vietnamese protest in Saigon on April 30, 2014 against the communist party.

The Vietnamese people are no longer afraid of the communist regime. They even beat up the cong an [police] who tried to disperse their rallies and demonstrations. Many demonstrators protested in front of the U.S. Consulate in Saigon against the oppressive communist regime. They hurled anti-communist slogans and called for the dismantlement of the VCP. In the meantime, one unthinkable event took place near by: The Catholic Archdiocese of Saigon organized a big reception to honor the former wounded and disabled veterans of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam. Over 400 veterans attended the reception, some of them wearing their ARVN [former south Vietnamese army] uniform.

There is a Vietnamese saying: "Gieo gio, gat bao" ("Who sows the wind will harvest the storm"). It is increasingly clear that the Vietnamese communist system is cracking under popular pressure. To avoid a rough landing and potential blood bath -- similar to the ones that had killed Romania's Nicolae Ceausescu and Libya's Muammar Gaddafi, the present leaders of the VCP would be well advised to relinquish power to the people and help build a free and democratic Vietnam. Otherwise, as the saying goes, they will harvest the storms of their own making.

Related article: "Vietnam is Poised for a Revolution, One Text Message at at Time."

Andrew Lam is an editor with New America Media and author of the "Perfume Dreams: Reflections on the Vietnamese Diaspora," and "East Eats West: Writing in Two Hemispheres." His latest book is "Birds of Paradise Lost," a short story collection, was published in 2013 and won a Pen/Josephine Miles Literary Award in 2014 and a finalist for the California Book Award and shortlisted for the William Saroyan International Prize for Writing.