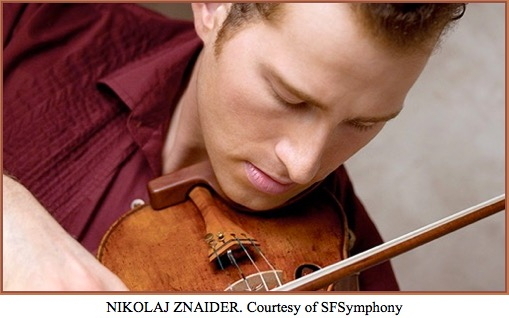

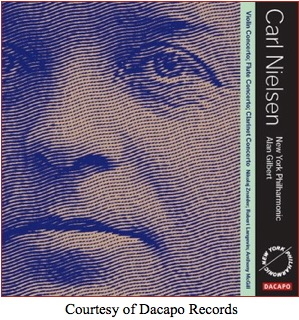

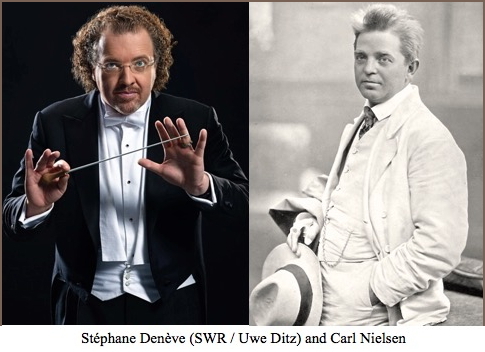

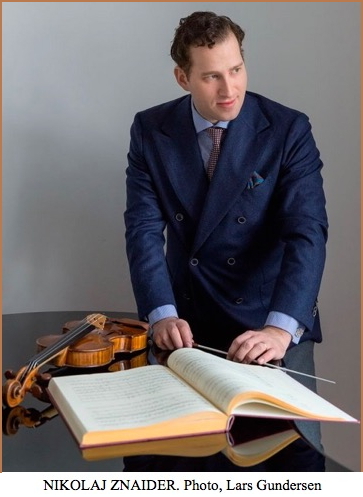

Violinist Nikolaj Znaider appears this week with conductor Stéphane Denève and the San Francisco Symphony, Thursday through Sunday, to play Danish composer Carl Nielsen's Concerto for Violin, Op. 33. The program will also include Une lueur dans l'âge sombre (A Glimmer in an Age of Darkness) by Guillaume Connesson and selections from Sergei Prokofiev's ballet, Cinderella. Nielsen's concerto, composed in 1911 while vacationing at the home of Nina Grieg (widow of Edvard Grieg), has clearly slipped past the attention of most audiences west of the Atlantic. Criticized early on as defying convention, even awkward - the work nevertheless resonates in the soul of Danish audiences as does Sibelius' Violin Concerto for the Swedes. In celebration of Nielsen's 150th birthday (9 June 1865), conductor Alan Gilbert and the New York Philharmonic released a CD on the Dacapo label, Nielsen: Violin Concerto, Flute Concerto; Clarinet Concerto - featuring respectively Nikolaj Znaider, Robert Langevin and Anthony McGill. The album is sensational. Nikolaj Znaider's illuminating performance squelches the narrow commentary of the anciens and re-introduces the work to a fresh and untainted audience.

"It's one of those very overlooked works by a composer who, in certain territories, is having a bit of a renaissance. But this piece for violinist is not one that is considered mainstream or even attractive to learn. Frankly, I don't understand! I don't think it's strange or awkward. Some theorist gave it an early judgement and, I think, condemned it to a kind of anonymity. It is difficult for conductors and I think that has something to do with it. But, more than anything, the concerto just never caught on. It's conventionally written and similar to all the other great Romantic concerti. But it's got this label of being difficult or awkward. I don't understand why."

"I played it a lot last year because of the 150th Anniversary. Invariably, with every interview I did I was asked, 'What's it like to play such a difficult concerto that is so awkward?' Again, who said it was awkward? I've played this piece since I was a teenager. To my ears, to my aesthetics - it is a very conventional Romantic violin concerto, like the Sibelius. We simply have to adopt a two-pronged attack or strategy. On one level, one needs to make sure that the piece is attractive to the organizers of concerts, to orchestral managements - who need to see the work as being attractive and not as something to avoid. Then we just have to repeat - as I did all last year during many performances of it - that it is a regular Romantic violin concerto. Beautiful, virtuosic and impressive. Absolutely worthwhile to listen to, to program, and to play."

SF Symphony has cleverly teamed the Nielsen concerto with two other works that are solidly based in imagery and storytelling. Connesson's Une lueur dans l'âge sombre was commissioned for the 2005 Season of the Royal Scottish National Orchestra and dedicated to its new Music Director, Stéphane Denève. The work is a flight of fancy, unfolding the composer's vision around the creation of a galaxy - ex nihilo - the sudden presence and harmony of something coming out of nothing. Likewise, Sergei Prokofiev's hit on the classic fairy tale, Cinderella. What stranger-than-fiction forces does a girl actually require to get out of obscurity and into The Palace?

About his violin project at Nina Grieg's (a sort-of Troldhaugen: Summer of 1911), Carl Nielsen said, "It has to be good music and yet always show regard for the development of the solo instrument, putting it in the best possible light. The piece must have substance and be popular and showy without being superficial. These conflicting elements must and shall meet and form a higher unity." Perhaps what the concerto requires at the outset is a super-charismatic musician who is unabashed about delivering a Tell All.

"One thing I am doing, is that I have agreed to become the President of the Jury for the Carl Nielsen International Violin Competition [in Odense, Denmark, April 16-22]. The competition has been going on for some years, but they've raised the level of admission. They approached me and I said, 'On two conditions. One, on the Jury - I don't want one person who is a teacher.' This seems to be the norm today, that teachers are on juries. Teachers invariably have conflicts of interest. The other condition was that I wanted the competition to provide real opportunity for a young gifted violinist to launch their career. Not just a lump sum of money and flowers, but to provide them with concert opportunities, mentorship guidance, and that the people on the Jury are not just musicians but also concert organizers, managers, etc. The reason I do this is to make the Nielsen Violin Concerto appealing. It must be played in the competition. This is one way I'm trying to create a positive influence on the next generation of violinists so that they have a relationship with Nielsen and that his concerto is a part of their repertoire early on."

"This is the responsibility we have as performers. We did not write the music. We are a medium through which this music has to come. We can either magnify it or minimize it. That's the big responsibility we have when are faced with these masterpieces - how to live up to them. How to make others feel what we feel and hear in this work. We need to find these kids as young as possible. The sooner the better. The reason I wanted to become a violinist was from watching Itzhak Perlman play on TV. I was eight. Then my parents took me to see him. That was it - that was the moment. I had been playing the violin already, but very unenthusiastically. It was after seeing him that I announced to my parents it was what I wanted to do. I think I said I wanted to be 'The World Champion of Violin'. I was into soccer at the time, so that was the terminology I used. The whole point of being a performing musician is to inspire in others the same love for the music we feel. That must be the driving force."